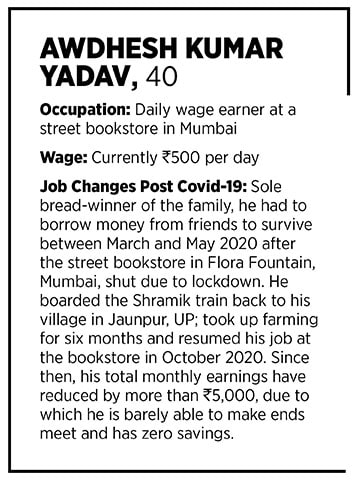

He had been working for a street bookstore owner at Flora Fountain in Mumbai, starting with a daily wage of Rs60 in 1999. He had left his village in Jaunpur, Uttar Pradesh, where his family practiced farming on one acre of land, and migrated to Mumbai to climb up the income ladder. Over two decades later, by early 2020, Yadav had started making close to Rs700 per day on the job and his monthly take-home income had increased to more than Rs20,000. The money, he says, had been sufficient to make ends meet every month.

When Yadav returned to Mumbai, he got back his old job, but nothing was the same again. “Pehle toh dhanda Rs5,000-Rs10,000 ka hota tha din mein, abhi toh bohot kam hai, sirf Rs2,000 to Rs2,500," he says, referring to the steep fall in daily sales at the bookstore.

For him, this meant a cut in his daily wages. He barely manages to earn Rs500 per day, which translates to about Rs15,000 per month. The wage cut continues to this date, and Yadav has no idea when the situation will improve, though he hopes it will, soon. At home, this has meant aggressively cutting corners. “No savings are possible with this income, not even a single rupee," he says. At least this was better than so many others he knows, who lost their jobs and have since not landed another one.

Covid-19 caused chaos in India’s jobs market: Rampant unemployment, changing nature of existing jobs, salary cuts, closure of offices, and diminished-to-no economic opportunities for daily wage and informal sector workers.

While migrant labourers walking back to their villages after the lockdowns last year was perhaps the most stark image of economic distress, quarterly bulletins of the latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) highlight data on the continuing unemployment crisis. In the April-June 2020 data released in March this year, unemployment increased to 20.9 percent, from 8.9 percent during April-June 2019. Numbers for June-September 2020 released earlier this month indicate unemployment at 13.3 percent, up from 8.4 percent in June-September 2019.

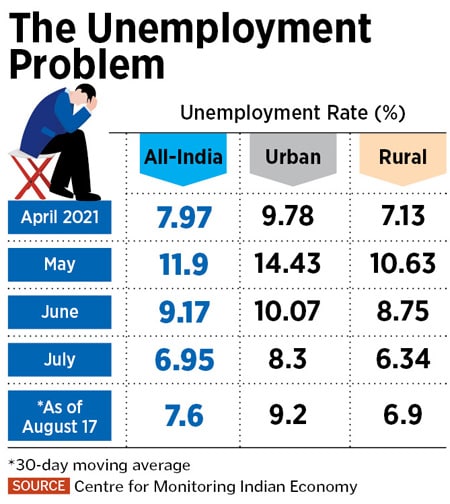

![]() According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), there are close to 40 crore [400 million] people employed in India. While the unemployment numbers fell to a four-month low in July (see table "The Unemployment Problem") in the wake of the ebbing of the second Covid-19 wave, “the number of salaried jobs, which are mostly better quality jobs, fell by 3.2 million [32 lakh]" compared to June, says an Economic Outlook report written by CMIE’s Mahesh Vyas on August 5. This was also 36 lakh short of the 8 crore salaried jobs before the second Covid-19 wave in January-March 2021.

According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), there are close to 40 crore [400 million] people employed in India. While the unemployment numbers fell to a four-month low in July (see table "The Unemployment Problem") in the wake of the ebbing of the second Covid-19 wave, “the number of salaried jobs, which are mostly better quality jobs, fell by 3.2 million [32 lakh]" compared to June, says an Economic Outlook report written by CMIE’s Mahesh Vyas on August 5. This was also 36 lakh short of the 8 crore salaried jobs before the second Covid-19 wave in January-March 2021.

“India entered the second Covid wave in a soft situation as far as the labour market is concerned: Work participation was still low, unemployment was high and incomes were also significantly below pre-pandemic levels. So the changes in the job market since have been huge, and also complex," says Amit Basole, director, Centre for Sustainable Employment, Azim Premji University. According to him, the economic distress caused by the pandemic is leading to a rise in agriculture or low-paying, non-farm occupations like casual labour or self-employment turning into fall-back sectors, which “is not a good sign".

The latest annual PLFS 2019-20 data, for instance, shows that the share of agriculture in employment increased to 45.6 percent in 2019-20, up from 42.5 percent in 2018-19. “This is the opposite of what we would want the case to be," Basole says. “One hopes that this is temporary and will reverse itself when we get out of the pandemic."

A large section of self-employment in India is driven mainly by necessities more than aspirations, says Sona Mitra, principal economist, Initiative for What Works to Advance Women and Girls in the Economy (IWWAGE).

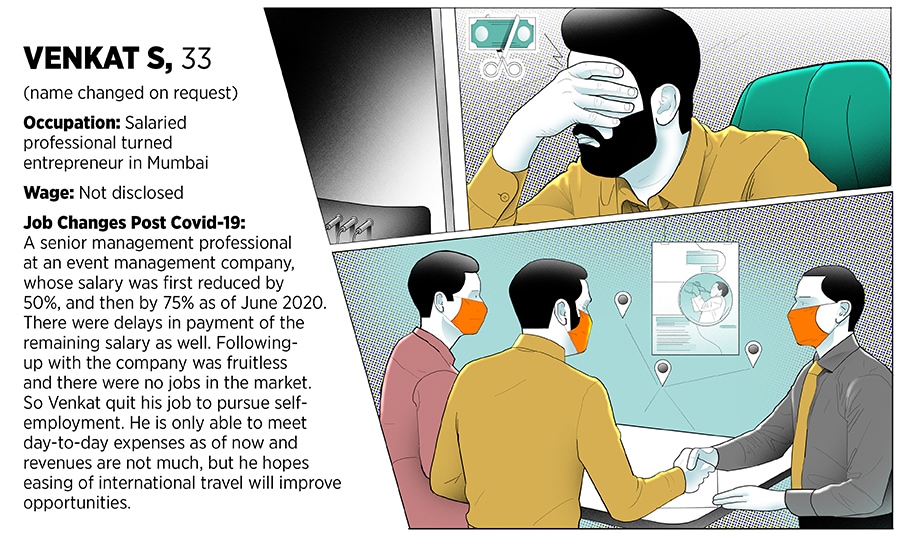

Venkat S (name changed on request), a 33-year-old Mumbai resident, was close to completing three years as a senior management professional at an international events company when the pandemic struck. Salaries initially reduced by 50 percent, and then by 75 percent in June 2020. There were delays of over 25 days in paying the remaining salaries too.

![]() “We did not get a single penny of incentives either. The owner of the company was clear that he will pay only when he has the money and there was no point following up," Venkat says. There were no jobs available in the events industry for senior management roles. Finally in August 2020, along with two other colleagues, Venkat decided to launch his own company that conducted events, conferences and training programmes for corporations. At least this way, he says, they would have full control over whatever money they manage to bring in.

“We did not get a single penny of incentives either. The owner of the company was clear that he will pay only when he has the money and there was no point following up," Venkat says. There were no jobs available in the events industry for senior management roles. Finally in August 2020, along with two other colleagues, Venkat decided to launch his own company that conducted events, conferences and training programmes for corporations. At least this way, he says, they would have full control over whatever money they manage to bring in.

In the past year, they organised 15 virtual events. Clients were from across Asia, Africa and the Middle East. “We are just meeting our day-to-day expenses right now and there are no revenues, but once international travel restrictions are eased, we hope that both work and revenues will pick up," Venkat says.

The PLFS 2019-20 report also highlights the discrepancies between money earned through salaries and self-employment. Average monthly earnings through salaries/wages was Rs17,600 for April-June 2020, which translates to roughly Rs587 per day. Average monthly earnings through self-employment for the same period was at Rs9,541, which is roughly Rs318 per day.

“A large majority of the self-employed workforce in India has earnings below decent wage limits. It is a very thin segment of self-employed professionals and big entrepreneurs who have higher earnings," says Mitra. According to her, the government has been pushing Startup India and Digital India by focusing on skill development of the youth, with an aim to push self-employment. “The demand-side problem of employment creation is at the lowest and still remains unacknowledged when it comes to policies," she says.

Even as 50 percent of the labour force is self-employed and policies continue pushing for more, it is important to create more and quality wage/salaried employment opportunities for the population, Mitra explains. “What happens is that while a few startups are successful for some time, it becomes difficult to sustain these successes. We have to create enough purchasing power and demand for these startups to be operational. And this purchasing power will only be created by wage employment opportunities. That is not being emphasised anywhere."

![]()

The pandemic has also deepened the problem of underemployment, where people have been forced to pick up any job available for survival, says Jayant Rastogi, global CEO of the Magic Bus India Foundation, a non-profit that runs one of India’s largest poverty alleviation programmes. “So now we have many talented individuals in sub-par jobs. This leads to a productivity issue in the market where we will have untapped potential going completely wasted," he says.

As part of their livelihoods programme that handholds adolescents and young job seekers through skilling and job placements, Magic Bus has worked with and trained close to 60,000 people from underserved backgrounds between 2015 and March 2021, about 25,000 of which came last financial year. The pandemic had led to a scramble and dire need for jobs and related skilling platforms.

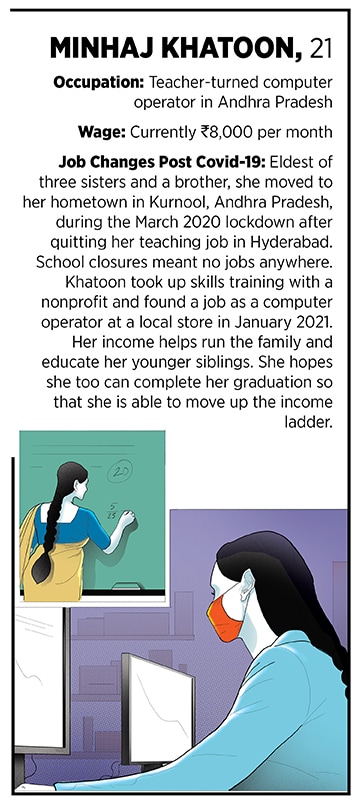

Rastogi claims they are looking at training over 100,000 people this year, with a focus on a minimum 70 percent job placements. The average salary earned is Rs11,000 to Rs12,000. Given the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on women, Rastogi ensures that at least 50 percent of people in their livelihood programmes at any point are women. Minhaj Khatoon and Vijaylakshmi are two cases in point.

Khatoon, 21, was a teacher earning Rs4,000 per month in Hyderabad when she had to move to her hometown in the rural Kurnool district of Andhra Pradesh in the wake of the lockdown last March. The eldest of three sisters and a brother, school closures meant she could not get any teaching job through the lockdown and even after that. “Koi jobs pe le hi nahin rahe the," she says. No one was giving her a job.

![]()

Her mother, a daily wage worker who got paid for the number of bidis she made, brought in some income. Khatoon was unemployed for 10 months, after which she finally landed a job in January as a computer operator following Magic Bus"s training programme. She now earns Rs8,000 per month. Khatoon, who could not study beyond class 12 due to personal and financial troubles at home, hopes she can take up her graduation studies soon, so that she can widen her employment prospects and “earn more money" in the future.

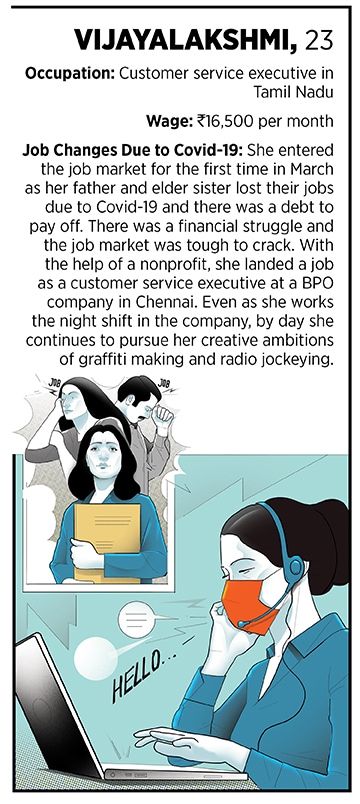

Vijayalakshmi, however, believes that because of the crisis caused by the pandemic, even experienced people are settling for entry-level jobs and lower salaries. The 23-year-old from Singapeumal Koil, about 40 km from Chennai in Tamil Nadu, aspires to be an artist, but had to start looking for a job—any job—after her father and elder sister lost their livelihoods due to the pandemic and the family had to survive on the income earned by her mother, who is a tailor. Vijayalakshmi says she struggled to give interviews and understand what the job market wanted.

In March this year, she landed a customer service executive role at Sutherland, a BPO company, with help from Magic Bus. Even as she travels an hour one way to and from Chennai, working the night shift, Vijayalakshmi has not stopped pursuing her creative career ambitions. She practices graffiti-making and is trying to land a gig as a radio jockey too. The Covid situation is likely to improve soon, she believes, and she wants to be ready to go after her dreams whenever opportunity strikes.

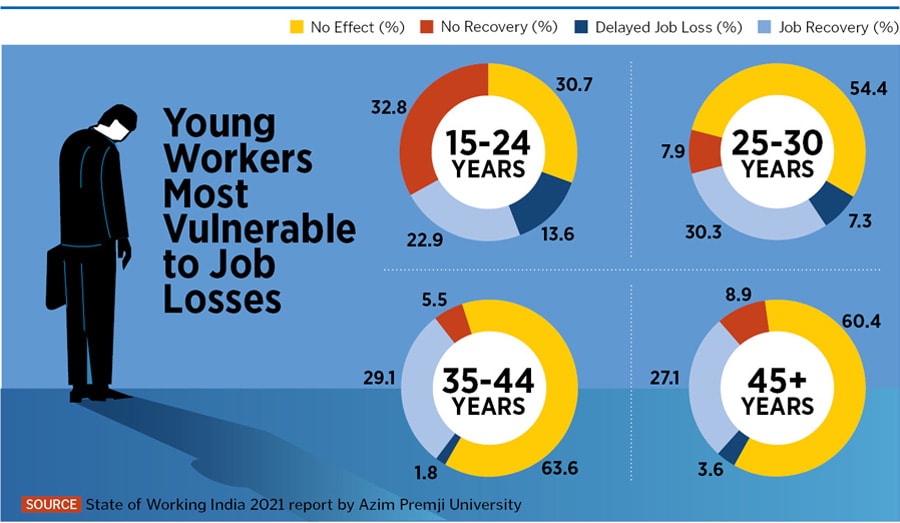

![]()

“A number of youngsters have entered the labour market when it is in bad shape, which can have a long-term impact on their career trajectory and earnings potential," says Basole of Azim Premji University. He explains that while the problem of job-readiness persists where youngsters have degrees, but not the relevant training and skills, a lot of the government skilling initiatives are focussed on the short term. “We need more imaginative programmes designed in partnership with the private sector, which creates the bridge between education and jobs," he says.

Rastogi agrees that it is essential to have an evidence-based approach where skilling is aligned with how the job market is shaping up. It is also important to find the balance between jobs in demand versus aspirations of the youth, and implement strategies accordingly, he says, “For example, there is a huge demand for General Duty Assistant roles in health care, but that job role is not an aspirational one for the youth, who are leaning towards sectors like IT, ecommerce, banking and financial services, retail etc," he explains, According to him, youngsters also have to be guided and counselled about how to steer their expectations through market realities.

![]()

Experts also call for an urban employment guarantee scheme on the lines of the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) for rural areas that generates quality employment opportunities. “Employment guarantees cannot be the end to solving labour problems in India," says Mitra of IWWAGE. “There have to be additional efforts in lifting industrial and manufacturing growth rates, and service sector opportunities for women and youth."

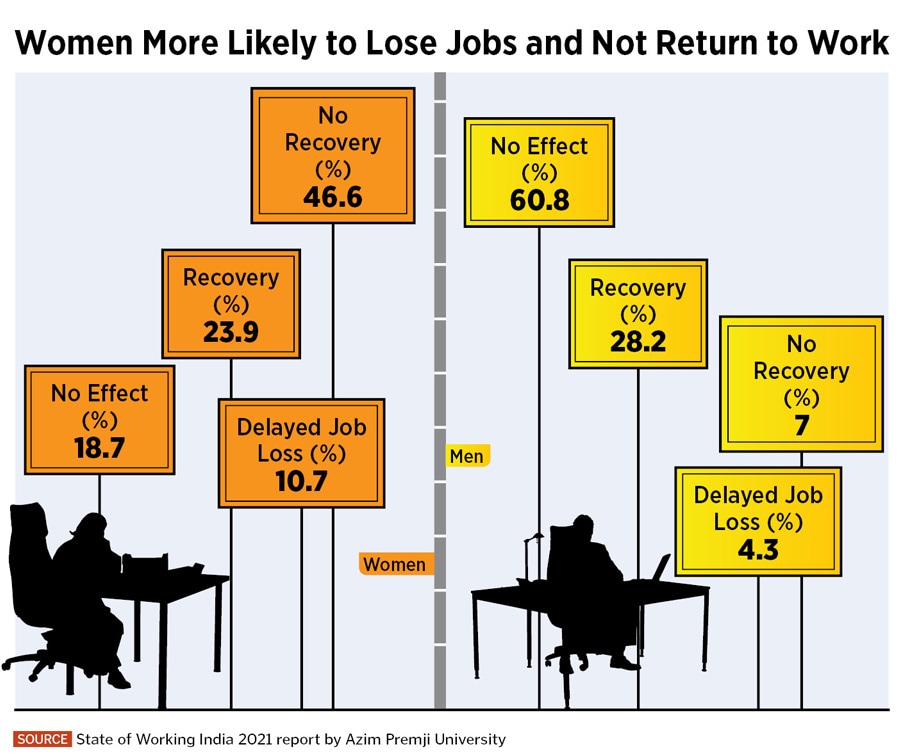

According to her, gender-sensitive employment policies, which take into consideration the disproportionate burden of unpaid care work on women, is the need of the hour. The PLFS 2019-20 shows that the gap between labour force participation of women and men continues to be significant. In rural areas, the participation rate (for people 15 years and above) is 33 percent for women as opposed to 77.9 percent for men. In urban areas, female labour force participation remained stagnant at 23.3 percent, compared to 75 percent participation for men.

Mitra explains that Covid-19 resulted in many women leaving the workforce and not coming back, because in view of lack of quality employment, they chose to invest in house work and child care instead of working in low remunerative job roles with bad working conditions. “Women have to be incentivised to come back to work and have to be provided with some kind of package that gives them hope of earning decent wages in the next one year that will cover for their losses [incurred in the aftermath of the pandemic]," she says.

This includes, according to her, targeted skill development across sectors and not just those that are traditionally dominated by women, universal child care facilities for working women, and infrastructure development in rural and low-income urban areas. “Right now, what the government is doing is ad hoc, coming in bits and pieces. We need to have one holistic policy," Mitra says.

Basole of Azim Premji University points out that unemployment and fall in incomes have also caused an increase in poverty and inequality. But this could be temporary if Covid-19 vaccinations pick up pace, confidence and demand come back, people return to work, and earnings are back to pre-pandemic levels. “Even if we set vaccination aside, it is not necessary that investments will come forth as needed and consumer demand will bounce back," he says, explaining that apart from extending distribution of free ration until November, the government has not announced any other measures since last year. “There have been no cash transfers. MGNREGA allocations are also not what they used to be during pre-pandemic levels. So my opinion is that a big fiscal action is needed."