By mid-2021—as vaccinations gathered pace and new Covid-19 cases slowed—business activity and sentiment improved. India’s GDP had soared by a robust 20.1 percent by June-end, simply due to a statistical low base of 2020. Investor sentiment boosted stock indices, rising 22 percent in 2021 and assisting corporates to raise fresh capital through record initial public offerings (IPO). But, by the end of the year, much of the euphoria turned into concern: The markets corrected over 10 percent from a Sensex peak of 62,254 points in October.

Foreign investors had intensified sales by then as global central banks announced plans to tighten liquidity and focus on battling inflation by raising interest rates. The Covid-19 virus was not done yet and the new variant B.1.1.529 (Omicron) spread across 125 countries from late November, hurting mobility and consumer sentiment.

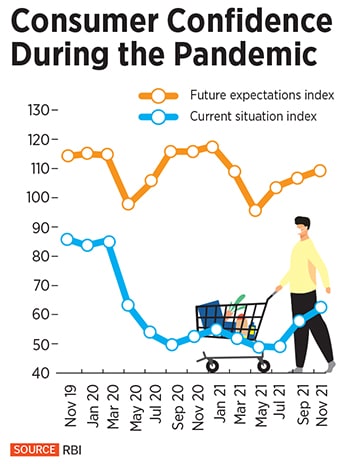

The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) recorded a fall in consumer sentiment in December 2021. The weekly index of consumer sentiments for the week ended December 26 was at 55.1, down from a year’s peak of 61.9 on November 21. “The fall in consumer sentiments in December after five months of an impressive rise raises some questions regarding the recovery of the economy," says Mahesh Vyas, managing director and CEO of CMIE, in his website column.

Will growth sustain?

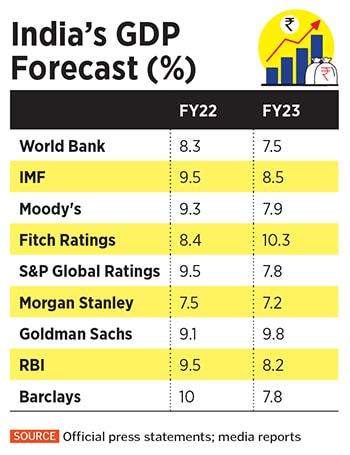

Several financial institutions and investment banks have projected India to grow in the range between 7.5 percent and 9.5 percent for the 12 months ending March 2022. But with uneven global growth, more emerging variants and concerns of a tightening of local interest rates in 2022, will India be able to take 2021’s success story ahead?

![]() The Nomura India Business Resumption Index inched p to 120.3 for the week ending January 2 from an upwardly revised 120.2 during the prior week. But Nomura’s chief India economist Sonal Verma says, “India seems to be on the cusp of a third wave" and warns of a rise in more cases due to “elevated mobility and a rising positivity rate". “While early signs point to a lower mortality rate, it bears close monitoring," she adds. India’s number of Covid cases (seven-day average) is back to a three-month high, at 22,939 on January 3.

The Nomura India Business Resumption Index inched p to 120.3 for the week ending January 2 from an upwardly revised 120.2 during the prior week. But Nomura’s chief India economist Sonal Verma says, “India seems to be on the cusp of a third wave" and warns of a rise in more cases due to “elevated mobility and a rising positivity rate". “While early signs point to a lower mortality rate, it bears close monitoring," she adds. India’s number of Covid cases (seven-day average) is back to a three-month high, at 22,939 on January 3.

“We are obviously seeing recovery but it is not yet broad based," says Crisil’s chief economist Dharmakirti K Joshi. The consumption of goods, rather than services, has gone up faster in the Western economies compared to India. Exports from India hit a lifetime monthly high in December last year at $37.29 billion, led by the booming IT/ITES sectors. The first nine months of FY22 (April to December 2021) showed a 48.8 percent jump in exports at $299.4 billion for the same period compared to a year earlier. Demand for exports grew as those economies moved out of lockdowns quicker.

Exports, and government capex, are expected to continue to drive growth in the next financial year, led by road projects awarded by the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI), which has been robust in FY22.

![]() But for the growth momentum to sustain, private consumption will be a critical factor. This, in all likelihood, will, in FY23, need to be driven by urban demand, possibly in the form of more jobs, better wages and the activity of contact-intensive services, including malls, restaurants, retail stores, movie halls and gyms. Joshi admits consumption at this stage is not broad based. “Contact-based services will take longer to recover. The urban poor have been hit harder than the rural poor who were benefited by several fiscal measures last year," says Joshi. Income disparity is being reflected in consumption disparity.

But for the growth momentum to sustain, private consumption will be a critical factor. This, in all likelihood, will, in FY23, need to be driven by urban demand, possibly in the form of more jobs, better wages and the activity of contact-intensive services, including malls, restaurants, retail stores, movie halls and gyms. Joshi admits consumption at this stage is not broad based. “Contact-based services will take longer to recover. The urban poor have been hit harder than the rural poor who were benefited by several fiscal measures last year," says Joshi. Income disparity is being reflected in consumption disparity.

The salaried middle-class and migrant workers faced the brunt in the first wave but in the second wave it was the rural poor who were struggling to acquire basic health care and emergency care services.

But Joshi, like other economists, forecasts a still-impressive pace of growth for FY23, even if it is a notch lower than the current fiscal. “If the Omicron impact strengthens, we would have crossed the third wave and services will show a rebound in activity due to pent-up demand." Joshi pegs India’s FY23 GDP at 7.8 percent which will normalise into FY24 at 6 percent, after the surge in pent-up demand will have faded away.

Private investment cautious, demand unhurt

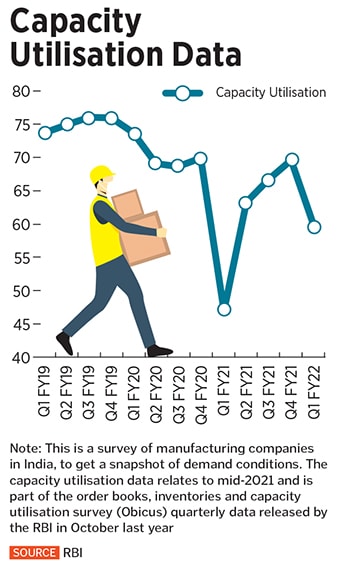

The government has been pushing for growth with fiscal spending on infrastructure projects, but the acceleration will need to come from the private sector. However, with uncertainty over business activity, corporates—despite strong performance-linked incentives from the government—may be slow on the pedal to push for fresh investments until obstructions clear. “Uncertainty is an enemy of investment decisions," Joshi says. In previous years, infrastructure and utility sector giants over-invested during bull runs of 2003-08 and 2010-11, often creating overcapacity, haphazard growth and led to rising non-performing assets and weakened balance sheets by 2015.

But Barclays chief economist Rahul Bajoria is not worried about Covid-19 hurting growth or demand. “Covid-19 will not be a demand [issue]. We will not see a pullback in demand," Bajoria says. It is a supply issue, in the sense, the impact would be due to government restrictions on mobility or access to services. “Consumption has recovered much faster than what most economists thought earlier. We have a glass half full view on the growth cycle."

![]() Economists feel the economy will bounce back from the Omicron threat this year. Construction, manufacturing and agriculture sectors are likely to remain unaffected in this fresh wave

Economists feel the economy will bounce back from the Omicron threat this year. Construction, manufacturing and agriculture sectors are likely to remain unaffected in this fresh wave

Image: Shutterstock

But while demand appears to be strong, companies are not rushing to invest. They will be risk-averse for a few more months despite some improvement in their balance sheets. This could mean that only some sectors, such as pharmaceutical and health care, would be looking to expand. Automakers will need to plan their car launches and build necessary inventory for those despite uncertainty due to supply constraints and pending bookings.

Carmaker Maruti Suzuki had in its September-ended quarter indicated that it will continue with its “strong launch pipeline" in the coming months, despite a dealer inventory of 60,000 cars and over 250,000 bookings pending at that time. But the company has not disclosed production or sales projections for the October 2021 to March 2022 period due to supply side uncertainty on account of semi-conductors. “What is unclear is whether companies will see a return to better capacity utilisation rather than there being a case for outright investment growth," Bajoria says. Several companies may want to wait to understand the impact of the fresh uncertainty as Omicron spreads.

Demand for domestic residential homes also appears to be on a firmer footing. “The pent-up demand got flushed out in 2020. Buyers are not willing to wait for 3-4 years [as seen pre-Covid-19] for occupancy they now seek ready-to-occupy or completely furnished flats," says Anuj Puri, chairman of Anarock Property Consultants. Unsold inventory of property in India’s top seven cities—Mumbai region, Pune, NCR, Bengaluru, Chennai and Hyderabad—has reduced by 19.2 percent to 638,190 units in 2021 from a 2016 peak of 790,500 units, Anarock data shows.

The pandemic has hurt income and household livelihood since 2020. The proportion of households where more than one person is employed has fallen to about 24 percent in 2021 from nearly 35 per cent in 2016. At the same time, households where only one person is employed has risen to 68 percent in the first 11 months of 2021, from 59 percent in 2016.

![]()

The gig economy had picked up towards the last quarter of 2021, but it might scale down a bit again. “This has got reflected in poor consumer confidence index," Bajoria says, where consumer confidence is low due to the lack of certainty [see chart]. Economists evaluate rural demand looking closely at the need for jobs through the government’s MGNREGA scheme. Nearly 11 crore people in India have demanded jobs in 2021-22, according to data from the Ministry of Rural Development. In the same period, 9.3 crore people were offered employment. Bajoria believes the demand for MGNREGA jobs in the first half of 2022 could be better (lower) than what we saw for the same period in 2021.

No dramatic rate tightening

Joshi and Bajoria do not foresee a sharp tightening of interest rates from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI). “There might just be a 50 bps of hikes in the reverse repo rate," Bajoria says. The RBI will need to continue to stay accommodative towards growth even as inflation rises. In the last year, inflation in India has risen more due to ‘imported inflation’—rising commodity prices and fiscal measures. But domestic sources of inflation, like food, were largely benign. In 2022, imported inflation may not rise further. The rate of inflation will start to come off.

![]() RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee is likely to keep interest rates unchanged in its February 2022 meeting. With the rise in the positivity rate in Covid-19 cases and spread of Omicron, there could be more restrictions on mobility which could prompt the RBI to not tighten rates and support domestic economic recovery and growth for some more time. The RBI has forecast India to grow by a lower 8.2 percent in FY23, compared to 9.5 percent growth estimate for the current fiscal.

RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee is likely to keep interest rates unchanged in its February 2022 meeting. With the rise in the positivity rate in Covid-19 cases and spread of Omicron, there could be more restrictions on mobility which could prompt the RBI to not tighten rates and support domestic economic recovery and growth for some more time. The RBI has forecast India to grow by a lower 8.2 percent in FY23, compared to 9.5 percent growth estimate for the current fiscal.

Maharashtra, Delhi, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Chandigarh, Haryana, West Bengal, Telangana and Karnataka have, in January, announced fresh restrictions on mobility and social gatherings. 2022 could see a fresh disruption in business and social activity, as in the previous two years. The ruling government has a tricky path ahead, with the need to keep room for more fiscal relief measures. It will also keep an eye on the upcoming assembly elections, particularly in Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Uttarakhand and Gujarat later in the year.

It is quite likely that the economy will bounce back from the Omicron threat at some point this year. Contact-intensive services might take longer to recover in their business cycles if restrictions continue to be imposed but it is unlikely that nationwide lockdowns will be imposed again, as in 2020. But urban jobs might once again come under pressure if people, from a health perspective, are unable to resume their jobs quickly. Construction, manufacturing and agriculture sectors are likely to remain unaffected in this fresh wave. Prompt fiscal and monetary measures will alleviate the pressures.

For the growth momentum to sustain in FY23, private consumption will be a critical factor. This will be driven by urban demand, in the form of more jobs, better wages and activity of contact-intensive services, including malls, restaurants, retail stores, movie halls and gyms

For the growth momentum to sustain in FY23, private consumption will be a critical factor. This will be driven by urban demand, in the form of more jobs, better wages and activity of contact-intensive services, including malls, restaurants, retail stores, movie halls and gyms The Nomura India Business Resumption Index inched p to 120.3 for the week ending January 2 from an upwardly revised 120.2 during the prior week. But Nomura’s chief India economist Sonal Verma says, “India seems to be on the cusp of a third wave" and warns of a rise in more cases due to “elevated mobility and a rising positivity rate". “While early signs point to a lower mortality rate, it bears close monitoring," she adds. India’s number of Covid cases (seven-day average) is back to a three-month high, at 22,939 on January 3.

The Nomura India Business Resumption Index inched p to 120.3 for the week ending January 2 from an upwardly revised 120.2 during the prior week. But Nomura’s chief India economist Sonal Verma says, “India seems to be on the cusp of a third wave" and warns of a rise in more cases due to “elevated mobility and a rising positivity rate". “While early signs point to a lower mortality rate, it bears close monitoring," she adds. India’s number of Covid cases (seven-day average) is back to a three-month high, at 22,939 on January 3. But for the growth momentum to sustain, private consumption will be a critical factor. This, in all likelihood, will, in FY23, need to be driven by urban demand, possibly in the form of more jobs, better wages and the activity of contact-intensive services, including malls, restaurants, retail stores, movie halls and gyms. Joshi admits consumption at this stage is not broad based. “Contact-based services will take longer to recover. The urban poor have been hit harder than the rural poor who were benefited by several fiscal measures last year," says Joshi. Income disparity is being reflected in consumption disparity.

But for the growth momentum to sustain, private consumption will be a critical factor. This, in all likelihood, will, in FY23, need to be driven by urban demand, possibly in the form of more jobs, better wages and the activity of contact-intensive services, including malls, restaurants, retail stores, movie halls and gyms. Joshi admits consumption at this stage is not broad based. “Contact-based services will take longer to recover. The urban poor have been hit harder than the rural poor who were benefited by several fiscal measures last year," says Joshi. Income disparity is being reflected in consumption disparity. Economists feel the economy will bounce back from the Omicron threat this year. Construction, manufacturing and agriculture sectors are likely to remain unaffected in this fresh wave

Economists feel the economy will bounce back from the Omicron threat this year. Construction, manufacturing and agriculture sectors are likely to remain unaffected in this fresh wave

RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee is likely to keep interest rates unchanged in its February 2022 meeting. With the rise in the positivity rate in Covid-19 cases and spread of Omicron, there could be more restrictions on mobility which could prompt the RBI to not tighten rates and support domestic economic recovery and growth for some more time. The RBI has forecast India to grow by a lower 8.2 percent in FY23, compared to 9.5 percent growth estimate for the current fiscal.

RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee is likely to keep interest rates unchanged in its February 2022 meeting. With the rise in the positivity rate in Covid-19 cases and spread of Omicron, there could be more restrictions on mobility which could prompt the RBI to not tighten rates and support domestic economic recovery and growth for some more time. The RBI has forecast India to grow by a lower 8.2 percent in FY23, compared to 9.5 percent growth estimate for the current fiscal.