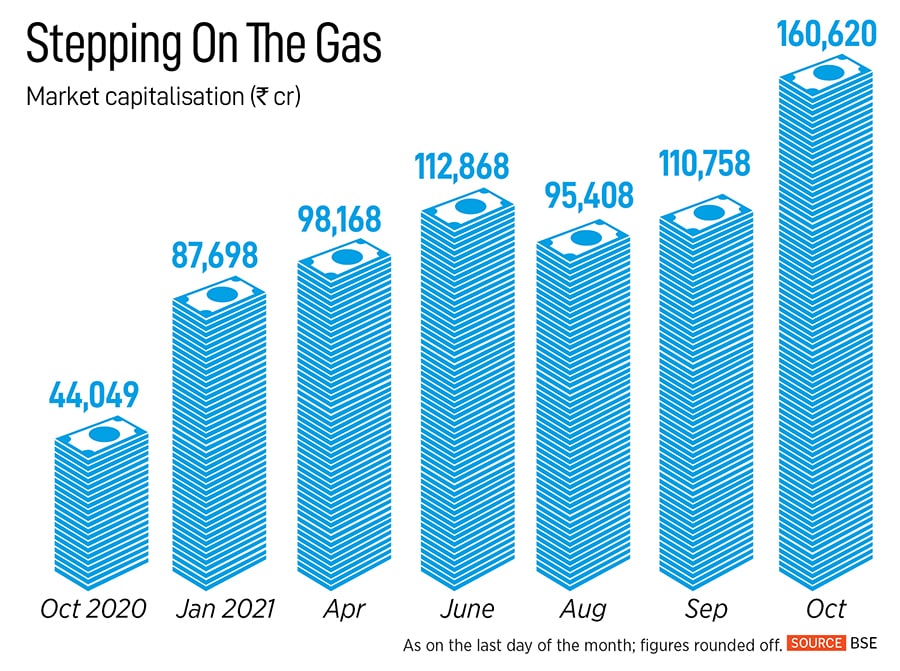

The stellar turnaround in sales has meant that the market capitalisation of the automaker, which also owns the iconic Jaguar Land Rover, has nearly quadrupled in the past year, even as India’s automobile industry grappled with an economic slowdown and lockdowns over the past 18 months. As of October, Tata Motors had a market capitalisation of Rs 1.62 lakh crore, up from Rs 43,800 crore last October. During the same period, the Sensex, the benchmark index of the BSE, grew by nearly 50 percent from 39,749.85 points to 59,252 points.

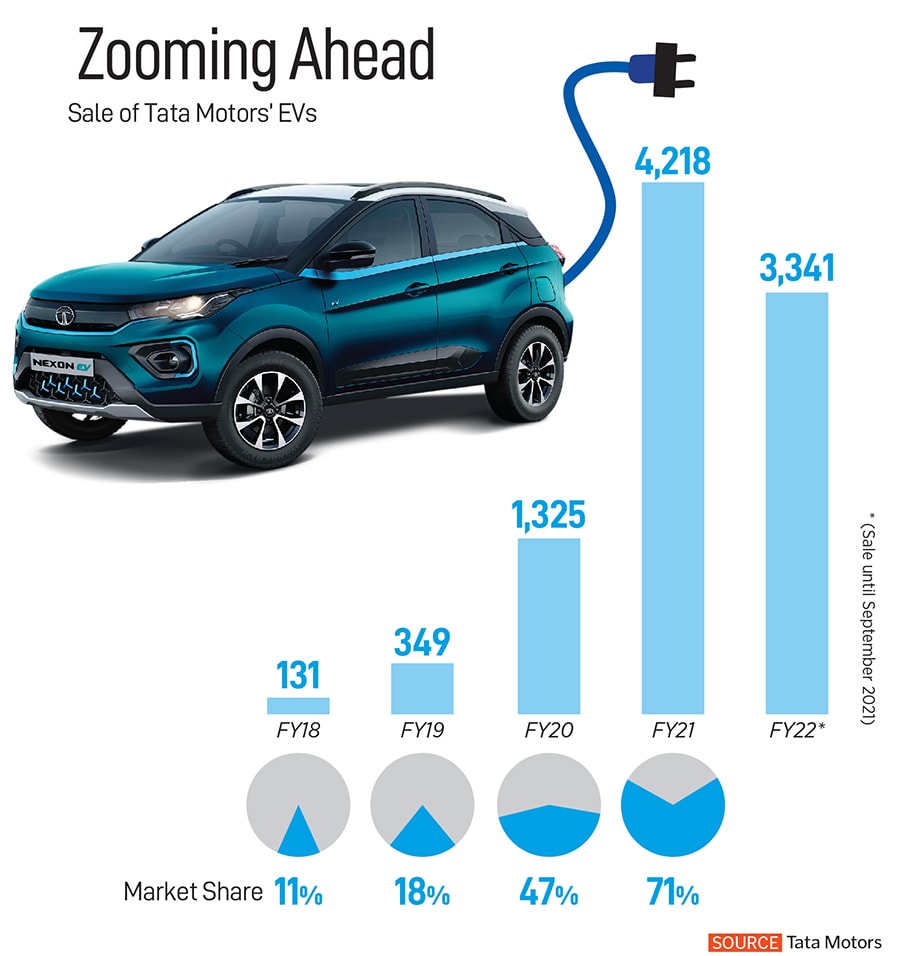

And there seems to be no stopping the Tata Motors juggernaut. Between July and September, sales of the 76-year-old automaker grew by a staggering 50 percent, led largely by a 193 percent growth in the company’s electric vehicle (EV) portfolio, comprising the popular Nexon EV and Tata Tigor EV. During that time, Tata Motors sold 2,700 units of its EVs, compared to some 900 units in the year ago period.

Those numbers mean that the company controls as much as 75 percent of the domestic EV market in India, especially since other manufacturers are yet to jump on to the electric vehicle bandwagon. Barring Hyundai, which offers the Hyundai Kona, several manufacturers, including India’s largest carmaker, Maruti Suzuki, and Toyota are yet to make EV offerings in India even as 10,000 electric vehicles manufactured by Tata Motors ply the Indian roads.

That’s also perhaps why it came as no surprise when over the past month, a subsidiary being set up by the company became India’s most valuable EV company, after raising $1 billion from private equity major TPG Rise Climate. The deal values the yet-to-be operational subsidiary at over $9 billion and the capital infusion is expected around March next year. Tata Motors will also invest $2 billion into the subsidiary over the next five years.

The new company, Tata Motors believes, will leverage all the existing investments and capabilities of the parent company in addition to channelising all the future investments into electric vehicles and dedicated battery vehicle platforms and technologies, among others. Over the next five years, the company will also create a portfolio of 10 EVs while also partnering with Tata Power to create charging infrastructure to help with early adoption.

“This is a big opportunity to lead the charge in this space (EV) and go about creating 10 products, and also create the ecosystem around it so that the aspiration of driving growth in electrification does not suffer because of lack of ecosystem," Shailesh Chandra, president of Tata Motors’ passenger vehicle segment, tells Forbes India. Chandra, who took over as president of the passenger vehicle business in 2020, had earlier been the head of the EV division, and has been instrumental in turning around the automaker’s fortunes over the past few years.

![]()

A large part of the turnaround, of course, is largely on the back of the increased sales of four vehicles that have now become the mainstay of the carmaker. Together, they form part of what Tata Motors calls the ‘New Forever’ range of vehicles, which boast high safety standards, better engine performance, and driving pleasure, aesthetic design, and rich features, in comparison to some of their previous models.

“Our focus over the past 18 months has been to ensure that we are able to get the rightful volumes for the products that we have created and everything else is consequential," Chandra adds. That means, from monthly sales of some 5,000 units of its Tata Nexon and 700 units of Tata Harrier a few years ago, sales have jumped almost three times in some cases over the last year.

“Tata is a leading player in the EV business with more than 70 percent market share and at the forefront of indigenous EV efforts while expecting green vehicles to generate 20 percent of their total sales in the next four to five years," Harshvardhan Sharma, head of auto retail practice at Nomura Research Institute Consulting, says. “In that capacity, this seems like a prudent vision to create a subsidiary which is insulated from conventional business operations for structural and operational efficiency reasons. As this subsidiary will be asset-light and as we understand the investments will align towards creating intellectual properties such as new vehicle designs and platforms in the EV space, this makes it a good fit from a business autonomy, flexibility, and pace of operations perspective."

The big leap

Much of the group’s foray into the EV business began in 2017.

That year, Tata was selected as a winner by the government-owned Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL) to sell some 10,000 EVs to the government. Tata Motors bid Rs 10.16 lakh per vehicle for 500 cars in the first phase of the government’s electric mobility mission. “At Tata Motors, we keep working on technologies and are quite ahead when a technology can be commercialised," says Chandra. “Therefore, we had been working on electric vehicles primarily at the Tata Motors European Technical Center from the early parts of the last decade."

The early part of the last decade saw the then-Manmohan Singh government announce the National Electric Mobility Mission which had aimed to transform the country’s EV penetration. That was followed by the highly popular FAME (Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Hybrid and EV) scheme to incentivise the production and promotion of EVs. Currently in its second phase—which runs until March 2022—it has an outlay of Rs 10,000 crore. The scheme is extended to cover electric two-wheelers, three-wheelers, and buses among others.

“In 2015, FAME was introduced for the first time. But the outlay was very small," Chandra says. “And still the direction was not clear whether it would be the pure battery-electric vehicle route or whether it would be hybrid. All those debates were on at that point in time."

By 2016, with the global trend moving towards reducing carbon emissions, and countries attempting to follow the Paris Climate accord, the global automobile industry had also begun tilting towards a battery-led EV play. India is a signatory to the Paris Climate Agreement, which means that the country needs to reduce its carbon emissions by around 35 percent of its 2005 levels by 2030.

“Unlike many countries, there was a bigger national imperative for the country given that we had 14 out of the 15 most polluted cities in the world," Chandra says. “And our dependence on imports of oil is very high. There is also an energy security issue from a geopolitical perspective which was also pushing the government." At that time, India was also in the midst of a transition to more stringent norms on emissions, which had meant that automakers were investing a significant amount of money in the transition.

![]()

“We knew that the technology shift was imminent towards electric," Chandra says. “It was going to come in a matter of five to six years."

It was around that time that the company also won the rights to sell vehicles to EESL. “The EESL order provided an anchor opportunity," Chandra says. “In the journey of electrification, it taught us how important it was to gain real-world experience, putting them in real use and the challenges of the working environment." As Tata’s vehicles began plying the roads, it also gave the company a fair understanding of the real-world conditions for an electric vehicle.

“It was clear that you have to enter the segment in a big way. And the personal segment is important because this is 90-95 percent of the total industry volumes," Chandra says. “Making a product is not sufficient. You have to really shape the electrification and go for an ecosystem approach." In April 2019, the government announced the launch of the second phase of FAME policy, which would encourage faster adoption of electric and hybrid vehicles by way of offering upfront incentives on the purchase of EVs. “That further refined our thinking in terms of the nature of products that we want to bring, and the price points. And there was the clarity of the localisation approach." (The government wants companies to localise their components to qualify for benefits.)

The big push

The company’s first offering in the private vehicle segment was the Tata Tigor EV, with a range of 213 kilometres on a single charge at a price of Rs 9.44 lakh. The older version of Tigor EV had a range of 142 kilometres but was largely sold only to EESL. The car came equipped with a 21.5 kWh battery pack and two charging ports for fast charging as well as slow charging.

By 2020, however, Tata was ready with a coup of sorts. The company unleashed the electric variant of the wildly popular Tata Nexon, priced at around Rs 13.99 lakh and with a range of 312 kilometres. The Nexon was one of the company’s highest-selling models, and the EV provided an opportunity to test the market. The Nexon, which was launched in 2017, was envisaged as a bridge vehicle as the company undertook a restructuring of its product platforms. Platforms are design architectures that include the underfloor, engine compartment, and frame of a vehicle.

“We did a survey, and it came out that the minimum range that a customer is looking for to avoid range anxiety is 200 kilometres," Chandra says. “That means a certified range has to go above 300 kilometres or so. At the same time, the customer is not willing to give more than 25 percent premium." That meant that the company’s best bet was the Nexon, which was retailing between Rs 7 lakh and Rs 12 lakh. “If you have to give a 300-kilometre battery pack in a Tiago, the cost will be the same, but the premium will be high."

In September this year, the company announced that it had sold 10,000 EVs in the country. “The extent of bookings that we are getting is between 3,500 and 4,000," Chandra says. “Last year, we had been ramping up supplies. At the start of this financial year, we were supplying around 600 vehicles which grew to 1,000 and then 1,100. We are now approaching closer to 1,500 supplies per month." In addition, the company has also launched the XPRES T electric sedan, an exclusive vehicle option for fleet customers. “We have a 100 percent market share there," adds Chandra.

“India’s EV revolution ideally should have been led by Maruti Suzuki as it’s the largest player," says Puneet Gupta, director for automotive forecasting at market research firm IHS Markit. “Instead, it is Tata Motors which is leading the revolution and is likely to be followed by Mahindra. Globally there is a paradigm shift underway when it comes to decarbonising the mobility sector and the Tatas clearly have a first-mover advantage. The ongoing pandemic has changed people’s mindset and that means Tata’s first-mover advantage will pay off."

Then, as part of its plan to bring in wider adoption, the group has built Tata UniEVerse, an ecosystem that will leverage group synergies, where several Tata companies have come together to provide EV solutions to consumers. The company has partnered with Tata Power to provide end-to-end charging solutions at home, the workplace, and public charging facilities. Under this partnership, the company has installed fast-charging stations in metros, including Mumbai, Delhi, Pune, Bengaluru and Hyderabad, in addition to chargers on highways. So far, Tata Power has set up 1,000 EV charging stations across India in some 180 cities.

![]()

The company has also tied up with Tata Chemicals in its attempt to build a component supplier ecosystem and manufacture lithium-ion battery cells, in addition to looking at active chemical manufacturing and battery recycling.

“The current technology and range specs are quite evolved frankly," Sharma of Nomura says. “We must keep in mind that these products have undergone much evolution since the introduction and Tata has been listening patiently to market feedback and hence the technology is fairly acceptable. Regarding range, there’s always going to be a difference between test conditions and real-world usage owing to climate, driving patterns, and terrains, but frankly, anything beyond 200 kilometres is good enough in the current scenario pragmatically."

A rounded play

Yet, it’s not that the company is entirely pivoting to EVs as many global manufacturers have announced.

Over the past few months, everyone from General Motors to Ford Motor Company, Volkswagen and Honda have been making commitments to shift their entire fleet to electric vehicles, over the next few decades. General Motors now plans to sell only those vehicles that have zero tailpipe emissions by 2035, while Japanese automaker Honda made it clear that the company intends to only sell EVs and fuel cell vehicles by 2040. In Europe, American automaker Ford said it will only be offering electric cars from 2030.

By 2025, Volkswagen wants to build and sell up to 3 million all-electric cars per year with over 50 purely electric-powered variants. All this follows the massive success story of Tesla, which has gone on to join the coveted trillion-dollar club after the company announced a plan to sell 100,000 vehicles to Hertz, indicating a massive shift underway from a demand perspective too.

“The Indian market story might be slightly different," Chandra says. “Today, the Indian passenger vehicle market would be 3.5 million units a year. If you fast forward to 2030, this will grow by double to nearly seven million. If you take a 30 percent penetration, it would mean two million EVs. There is an opportunity on the EV side to grow from zero to two million." The rest of the seven million, Chandra reckons, will be ICE vehicles. “So, there is a growth opportunity in both these spaces," Chandra says. “ICE vehicles will become more emission friendly."

![]()

That’s why the company is looking to launch as many as 10 new products over the next decade. That includes first-generation vehicles, which are essentially ICE vehicles that will be converted to electric vehicles. That will be followed by architectures that will be suited for EV and ICE vehicles and eventually born EVs. Much of the work will be undertaken at the company’s EV facility in Pune and Chandra and the team are currently in the midst of setting up the subsidiary. The automaker is also lining up a $2 billion investment towards product development while also planning to launch sales in over 100 cities and some 255 touchpoints through the year.

“Our teams will be separate, and that’s the reason why you’re seeing us creating two different companies," Chandra says. “One will fund itself and be able to support its growth and investment in new technologies, platform, and product lifecycle management. The other requires a massive investment phase which is why we went for separate funding." As of now, the company has a 60 percent localisation of its components, which it wants to ramp up to 85 percent by 2025.

Meanwhile, it’s not just passenger vehicles that Tata Motors is betting on to drive the change.

The commercial vehicle division, which comprises buses, trucks and light commercial vehicles, is also beginning to witness higher electrification. So far, Tata Motors has supplied a total of 618 e-buses that have run approximately 20 million kilometres to date.

“The number of vehicles we have been selling would have been higher if not for Covid-19," says Girish Wagh, head of commercial vehicles at Tata Motors. “There has been a collapse in the bus market. But, with the cost of vehicles increasing with every emission regulation and rising fuel prices, the total cost of ownership parity is becoming closer and closer when it comes to electric vehicles."

That means even though sales are now largely led by government orders, the company reckons that private buyers, especially corporates and ecommerce companies, could lead the charge when it comes to the adoption of EVs. “Corporates have their own net-zero targets," adds Wagh. “Ecommerce companies, which are focusing on last-mile connectivity, are also seeing benefits in operating costs." At the moment, Tata’s electric buses have a range of over 100 kilometres which it plans to ramp up to between 140 kilometres and 200 kilometres.

Then, there is also the focus on alternative fuels, such as hydrogen fuel cells, which Wagh reckons is crucial when it comes to long-range travel. “Battery electric vehicles are generally suitable for the lower range and lower power," Wagh says. “But when you start looking at commercial vehicles and the medium-heavy commercial vehicles, they generally travel 1,000 kilometres a day. They also carry 10 tonnes to 15 tonnes of load. So, it’s a completely different kind of transportation and there, battery-electric doesn’t work, and that’s where we work with hydrogen."

The path ahead

It helps that the global automobile ecosystem is now shifting towards EVs. Then, over the past few years, India has seen a significant rise in fuel prices. India’s import of crude oil required for vehicular fuel has been increasing over the years. It stood at $40 billion in 2017 and is projected to more than double to $90 billion by 2030 at the current pace. At the same time, battery cost has reduced from $800 per kilowatt-hour in 2011 to $137 per kilowatt-hour in 2020.

According to Niti Aayog, the country’s EV financing industry is projected to be worth Rs 3.7 lakh crore in 2030, about 80 percent of the current retail vehicle finance industry.

Between 2020 and 2030, the estimated cumulative capital cost of the country’s EV transition will be Rs 19.7 lakh crore across vehicles, electric vehicle supply equipment, and batteries (including replacements).

“Tata’s commitment to EV cements the belief in electric power trains being a near future in India and not being an exotic propulsion system for developed markets only," says Sharma of Nomura. “The market has surely taken notice of this shift and both OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) and consumers respect and appreciate this development. Tata is leading the electric mobility chapter in India from the front, and we see its payoff panning out well for Tata as they are co-developing the ecosystem and hence addressing a much wider part of the value chain."

“There is a broad scenario of how the whole penetration will move and therefore we have set certain aspirational targets," Chandra says. “We are working towards that and the network planning and charging infrastructure planning is being aligned to that. This kind of an opportunity will attract people and some of them will take a proactive approach like us and some would just like to wait and watch."

![]()

Despite all the narrative around EVs, there haven’t been substantial gains. Last year, India sold some 156,000 units of EVs, of which 126,000 were two-wheelers. In contrast, over 21 million vehicles that run on internal combustion engines were sold in FY20, of which 17 million were two-wheelers. China sold some 1.3 million EVs in 2020, according to Singapore-based market research firm Canalys, in a year marked by a pandemic, accounting for over 40 percent of the global EV sales. “This is an industry where word of mouth is crucial," adds Chandra.

All that means Tata Motors has a long way to go, and it’s only getting started after its phenomenal turnaround in fortunes.

“I see the future of electric vehicles to be very strong," Chandra says. “EVs have better running cost and better performance. The only concern is about technology." To alleviate that, the group has been offering an eight-year warranty on the vehicle. “Our competitive advantage is that I’m working in a synchronised fashion with Tata Power, and we are therefore working closely with them in terms of aligning the location of the charging units to where we are selling the cars."

Meanwhile, the company is also aware of the challenges that the global electric ecosystem can throw up. “There will be a lag on the supply side versus demand ramp-up which will happen, and the battery would be one of the key components because today I would imagine that the global capacity of batteries would be 250-gigawatt hours. Fast forward 10 years from now, the requirement might be 2,500 gigabytes," Chandra says. “Therefore, there can be stress going forward, but at the same time, there are entrepreneurs across the world who would like to ride this wave, so they would also be proactively thinking about it."

So, will the first-mover advantage really work? “While they have a first-mover advantage, the combined Kia-Hyundai entity could be a challenge in the future," adds Gupta of IHS Markit. “The Koreans have a significant advantage when it comes to the battery supply ecosystem. But so far, their focus has been on the Rs 15 lakh to Rs 25 lakh market. Others like the Japanese will push until the last minute to stay away from the transformation but it is inevitable. That means, as the first mover, Tata has a massive opportunity, and a challenge in front of them."

Who better than the Tatas to turn a challenge into an opportunity.

Shailesh Chandra, president of Tata Motors’ passenger vehicle segment, has been instrumental in turning around the automaker’s fortunes over the past few years.

Shailesh Chandra, president of Tata Motors’ passenger vehicle segment, has been instrumental in turning around the automaker’s fortunes over the past few years.