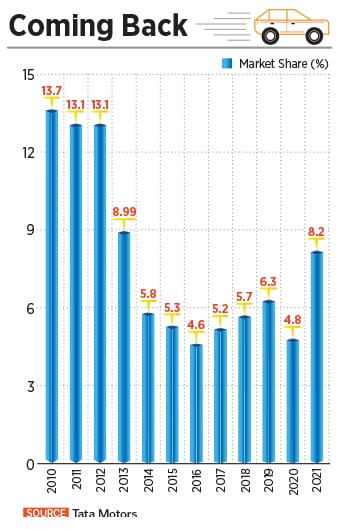

Over the past decade, the Rs 1.05 lakh crore automaker has seen its fortunes tumble in the Indian market, even prompting questions about its relevance in the country’s $104 billion automobile industry, before it began staging a whirlwind comeback.

From a paltry market share of 4.6 percent in 2016, and 4.8 percent in 2020, Tata Motors is now India’s third-largest carmaker, boasting a market share of well over 9 percent in the world’s fourth-largest automobile market. In FY21, the company sold 222,025 units of passenger vehicles, a 69 percent growth in comparison to the year-ago period. In contrast, the country’s passenger vehicle sales in the fiscal fell by 6.2 percent. This April, the company accounted for 9.16 percent of the domestic market, up from 8.77 percent in the previous month, according to the Federation of Automobile Dealers Association.

The phenomenal turnaround also comes at a time when the country’s automobile industry has been stuck in a quagmire for the past few years, with sales dwindling due to a slowing economy, transition into eco-friendly engines, and the Covid-19 crisis. Incidentally, the reversal in fortunes also came after a decade of turbulence when Tata Motors, which made iconic Indian vehicles such as Tata Indica, Tata Sumo, and Tata Safari in the early parts of the millennium, was left on the fringes in the highly competitive Indian car market. With dwindling sales, mostly catering only to the fleet taxi market, the carmaker had fallen out of the radar with personal buyers.

A slew of second-generation vehicles that replaced the company’s much successful first-generation models in the late 1990s and early 2000s, such as Indica, Safari, and Sumo had failed to entice buyers and replicate its initial success, forcing the automaker to go back to the drawing board and come up with a new strategy to revive its struggling passenger vehicle business. A decade ago, Tata Motors held more than 13 percent in the domestic market, which it kept losing steadily to domestic and foreign carmakers.

And through it all, Chandra knew the key was to see through the tough times with his head down and focus on the final outcome. “The commitment of the leadership and the board to the passenger vehicle business was never in question, and it was unfortunate that the second generation (of vehicles) did not work," says Chandra. “We knew if we hit the sweet spots of the market, it will work. There was a phase we had to go through, and it was a time we had to make sure that we"re never forgotten in the market."

In the past year, perhaps, in a strong show of confidence among investors, Tata Motors’ share price has more than tripled, with a market capitalisation of over Rs 1.05 lakh crore. In May, rating agency Moody’s upgraded the outlook from “negative" to “stable" largely due to a continued recovery in the company’s consolidated revenue and profitability, in addition to stronger credit metrics at the company.

"The rating affirmation and change in outlook to stable reflect the continued recovery in TML"s (Tata Motors Limited) consolidated revenue and profitability from the trough during the pandemic in the first quarter of the fiscal year ending March 2021," Kaustubh Chaubal, vice president and senior credit officer at Moody’s said in a report. “We expect the recovery to sustain over the upcoming 12 to 18 months, strengthening TML"s credit metrics."

What worked now

Much of the turnaround over the past few years is largely on the back of the increased sale of four vehicles that have now become the mainstay of the carmaker. Together, they form part of what Tata Motors call the “New Forever" range of vehicles, which boast high safety standards, better engine performance, and driving pleasure, aesthetic design, and rich features, in comparison to some of their previous models.

The Nexon, which launched in 2017, the Harrier in 2019, and the Altroz in January 2020, contributed to as much as 60 percent of the sales in the last fiscal. Of that, Altroz and Harrier were manufactured on the Alfa and Omega platforms, respectively. The two platforms, the first of which was introduced in 2018 on the Harrier and later the Altroz, marked a shift in the company’s practice of developing specific platforms for every model. There is also the company’s hatchback, Tiago, which was initially christened Zica, that has been holding steady in terms of sales, and clocking over 6,000 units a month since the past few years.

![]()

Platforms are design architectures that include the underfloor, engine compartment, and frame of a vehicle. Having just two platforms helps streamline manufacturing, reduces development and manufacturing costs, unlike earlier when there were multiple platforms for various models. It also helps with capacity utilisation, reducing risks, and improving vehicle reliability, and reducing time to market. The Omega platform was based on the wildly successful SUV Discovery, owned by Tata Motor’s subsidiary Jaguar Land Rover.

“Out of the many SUV platforms available at Land Rover, D8 was evaluated and found to be most suitable for the evolving Indian market," Chandra says. “The optimisation of the platform in terms of materials and innovative manufacturing technologies helped the team to keep the costs under control without touching the core characteristics, thus leading to the development of our Omega Architecture." The Altroz was built on the indigenously developed Alfa platform.

While the shift to the new platform began only in 2018, Tata Motors also saw off a period post-2016, when it had to rely on what it calls “bridge products" that would help bring traffic to the showrooms, and in the process, recall value for the brand. Much of those bridge products relied on the company’s new design philosophy and safety features.

“There was a period where we had to bring bridge products to bring excitement among personal consumers, and the backbone of that became impact design and safety," Chandra says. “The bridge products were the Tiago, Tigor, and Nexon of which the Nexon was in between the old and new architecture, and that helped us come back strongly. But even that was only to a limited extend."

The Nexon has truly changed the fortunes of Tata Motors. “In many ways, it was the game-changer," says Puneet Gupta, the director for automotive forecasting at market research firm IHS Markit. “Somehow it managed to understand the pulse of the customer. There is no doubt that the past five years have seen a significant turnaround and most of their launches during this time have been timely and targeted the mass segments. Along the way, they also ensured they addressed issues of quality and even brought on board global suppliers which helped quality standards." In the last fiscal, Nexon was the top-selling vehicle for the group.

Of course, much of the credit for the recent turnaround at Tata Motors’ passenger vehicle business must also go to the company’s CEO Guenter Butschek, who joined the automaker in February 2016. The month before, Tata Motors sold a paltry 10,728 units of passenger vehicles in the country. By the time he came on board, the company was selling 149,420 units of passenger vehicles a year. That grew to 172,504 in 2017 and 210,200 in 2018. By 2019, the company was selling almost 100,000 units more than what it did in 2016 to close at 231,572. However, 2020 was a lacklustre year as vehicle purchases across the country fell significantly on the back of poor credit and the Covid-19 crisis.

After the company began sales in May 2020, it clocked well over 21,000 units every month. Last year, Tata Motors sold 222,025 units despite much of April and May not seeing any sales due to the nationwide lockdown. It also helped that an ongoing resentment against China as a result of the border skirmishes in 2020 led to a push for more domestic products. Tata Motors meanwhile unleashed a digital campaign, Atmanirbharta by Tata Motors, highlighting localisation in the company’s products.

“The journey of winning back our market share has been on the back of a long-term strategy, which took into consideration the changing market trends, in terms of changing customer preferences, segmental shifts, regulatory changes, and technology shifts," Chandra told Forbes India. That also meant understanding the key differentiating pillars and a renewal of the product portfolio to become future-ready. “There was also a shift in our focus towards world-class quality in product development and manufacturing systems." Among others, the company also began offering world-class brands and components such as JBL or Harmen in its vehicles.

In 2018, the company’s hatchback, Tata Nexon, became the first made-in-India, sold-in-India car to achieve Global NCAP’s coveted five-star crash test rating. That was followed by the Altroz, which in 2020 became the second car from the Tata Motors stable to win five stars in the ratings.

The genesis of the repeated success in meeting global safety norms lies in the groundworks that the company laid out in 1998, Rajendra Petkar, the chief technology officer at Tata Motors had told Forbes India earlier. “If you look at it, it’s not that we made some structural changes in the past few years," Petkar had said. “It dates back to the time of the Tata Indica in 1997." Tata Motors was the first Indian manufacturer to invest in a crash test facility in 1997, a time when there were no crash-testing benchmarks in India.

Yet, none of that would have worked had it not been for the rethinking of the company’s rather tasteful designs, helmed by Pratap Bose who has now left the company after 14 years. “Introduced in January 2018. Impact Design 2.0 is a sharper, more contemporary expression of Tata Motors’ Design language, which immediately captures the attention of the customers," says Chandra.

Then, last July, Tata Motors upgraded its flagship SUV, the Harrier, giving it more power as part of the company’s plan to meet India’s environmental norms. The Nexon too got a facelift and an engine upgrade. “Our strong comeback in FY21 and reclaiming our 3rd rank has been on the back of unleashing the full potential of every product in our portfolio," Chandra says. “Re-imagining the front end has created a strong foundation entailing robust channel health and engagement. The Tata brand is also witnessing a jump in terms of, awareness and consideration. There has been a fostering of a culture that focuses on retail, and bringing end-to-end value-chain alignment and systematic micro-market actions."

This will go a long way in roping in more buyers, especially across various price points. “At the downstream side, Tata Motors has been upping its ante with simplification and digitising of customer journeys and by offering an array of financing options with low EMIs, longer tenures, and up to 100 percent on-road funding," says Harshvardhan Sharma, the head of automotive retail practice at Nomura Research Institute Consulting & Solutions. “This means that now Tata Dealers have products starting from Rs 5 lakh to Rs 20 lakh, so effectively there’s a car for everyone, making the mix sustainable for dealers."

It also helps that most of the current models have 10 to 14 variants, which allows for a choice for the buyer at every Rs 20,000 mark. “What’s even remarkable is that average selling price has been growing and tactical offers (discounts) have come down significantly, indicating a shift to value-based selling instead of price point-based approach," adds Sharma.

All that only means the brand has now returned to being among the top considerations while making a purchase. “Five years ago, the brand had very little recall value," says Gupta of IHS Markit. “Many had stopped considering it while purchasing vehicles. But there were a lot of changes to the process that were made in addition to ensuring quality. Tata Motors also kept refurbishing their dealer network, bringing in new energy. Today, there is no doubt that the company is among the real frontrunners in the passenger vehicle market."

Timely intervention

Of course, the lessons from the past decades have a significant role in what lies ahead.

To begin with, the company will certainly have to ensure it doesn’t lose its share of personal buyers once again, in addition to continuing to churn out products that can excite the market. Among others, future launches from the Tata stable include the Tata HBX, codenamed Hornbill, a new micro-SUV, apart from electric variants of its popular models including the Altroz. In February, the company had launched its iconic Safari, which sits above the Harrier.

“Tata Motors is a classic turnaround story, one of an Indian brand that not only survived but thrived among the behemoths of auto industry globally," adds Sharma of Nomura. “The strategy of expanding their portfolio and faster time to market seems to have worked well combined with gains from focusing on customer-centricity and cost rationalisation."

That was something, that was certainly missing earlier. “We did not even address 50 percent of the market because we had no product," Guenter had told Forbes India. “We invited the competition to take our space, and it had nothing to do with changes in the regulatory environment. It was just our inability to take quick actions and translate changes into a proper product."

That meant, with the company losing out on the domestic market between 2006 and 2017, and profits taking a serious hit, its suppliers and dealers too were being hit hard by sluggish sales. That also brought with it some serious domino effect of heavy discounting that was followed by a vicious cycle of even more profit erosion. “An even greater concern was that the majority of sales were attributed to the fleet segment which, as most OEMs would agree, is a taxing segment to operate in," says Sharma.

Meanwhile, Chandra who took charge last May, reckons the carmaker, with its current portfolio of six vehicles, is already “doing much better" than many of its rivals who have eight or nine products in their portfolio in the domestic passenger vehicle market. “With five or six products we are doing much better than players with the 8-9 products and in an addressable market which would be between 50-55 percent of the total industry volume (TIV)," Chandra says.

All that has meant that the company is on a reasonably strong footing now, compared to a few years ago. During the January-March quarter of FY21, it posted a net profit of Rs 1,646 crore on a standalone basis, as against a loss of Rs 4,871 crore in the year ago period. Revenues on a standalone basis more than doubled to Rs 20,045 crore during the same period. “Passenger vehicle absolute Ebitda is the highest in last 10 years," the company said while announcing its results. “Cash savings of Rs 9,300 crore was delivered against a target of Rs 6,000 crore.

On a consolidated basis, however, Tata Motors had a difficult year largely due to a one-time restructuring underway at Jaguar Land Rover. The company reported a consolidated loss of Rs 7,605 crore in the March quarter, as it had to write off some Rs 15,000 crore at JLR as part of the electric powertrain-focused Reimagine strategy underway at the British automaker. For the full financial year 2020-21, the company reported a consolidated net loss of Rs 13,395 crore, against a net loss of Rs 11,975 crore in the previous year.

“JLR"s restructuring efforts and its solid growth in China, as well as the recovery in other key markets such as Europe and North America over the coming quarters, will improve its profits and leverage," Moody’s said in its May report. “Success from new product launches earlier this year such as The New Safari and HBX expected to be launched later in 2021 along with its other products such as Altroz, Nexon, Harrier and its variants constitute a wide offering across hatchback, sedans and SUVs, which should help TML to further strengthen its market position."

The company is now looking to hive off its passenger vehicle business into a separate subsidiary to look at partnerships and alliances as it looks to its next phase of growth in the new decade. “The subsidiarisation process is currently ongoing and expected to complete over the next few months. It will enable PV business to explore and forge mutually beneficial strategic alliances for access to products, architectures, powertrains, new-age technologies, and capital," says Chandra. “While securing a mutually beneficial alliance is a priority, it is not an imperative for today but an opportunity to be secured for tomorrow."

Now, as the Covid-19 crisis rampages through, Chandra and Tata Motors know it’s not an easy task to sustain the turnaround. “Going forward, our strategy will be to ensure the strengthening of our product portfolio in terms of competitiveness, and a comprehensive set of powertrain and technology options," says Chandra. That means further enhancing the portfolio towards a higher addressable market, including strengthening the SUV portfolio. Then, there is also a focus on the electric vehicle business, which Tata Motors sees as a considerable play in the future. Already, the Nexon’s electric variant has leapfrogged to one of India’s top electric vehicle models.

“The last decade and this decade are different," Chandra says. “This is the most difficult decade for the industry with multiple transformations with technology, safety, and climate changes driving the changes. That would mean further investment and one needs to manage the investments carefully. At the same time, the market is ruthless in terms of what the consumer wants to buy. That would mean collaborations as well, but it’s not a desperate need for the day."

So where does Tata Motors go from here? “We want to get into the double-digit zone of market growth," Chandra says. “In the next 6-7 years, differentiating ourselves on safety, design, and driving pleasure will be a priority. We have not unleashed our full potential, and we are one of the manufacturers with the highest levels of pending orders, which means the potential is huge."

The rough tide has passed. Tata Motors has managed to stay afloat and anchor itself well. Now for the smooth sailing.

Graphics: Pradeep Belhe

Shailesh Chandra, President - Passenger Vehicles Business Unit, Tata Motors at Ahura Centre, Mumbai Image: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India[br]

Shailesh Chandra, President - Passenger Vehicles Business Unit, Tata Motors at Ahura Centre, Mumbai Image: Neha Mithbawkar for Forbes India[br]