How to tame the elephant in the economy

The RBI expects inflation to peak by the quarter ending March, but that may depend on a clutch of imponderables

The rise in core inflation—which excludes food and fuel—is a big concern. The central bank largely uses consumer surveys to gauge inflation, and expects CPI or retail inflation to peak at 5.7 percent in the fourth quarter of the current fiscal. Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

The rise in core inflation—which excludes food and fuel—is a big concern. The central bank largely uses consumer surveys to gauge inflation, and expects CPI or retail inflation to peak at 5.7 percent in the fourth quarter of the current fiscal. Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur

"Price stability remains the cardinal principle for monetary policy. Our motto is to ensure a soft landing that is well timed."

- Shaktikanta Das, RBI governor

This statement reflects the unrest in the minds of most global central bankers as they precariously tackle "stubborn inflation" and focus on the "overarching priority at this juncture to broaden the growth impulses’. In this spirit, Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Governor Shaktikanta Das checked all the boxes in his earnest attempt to assure the Street that the central bank would remain "accommodative as long as necessary to revive and sustain growth on a durable basis", even though "the monetary policy is reaching an inflection point’.

In line with this, on Wednesday, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) decided to retain its accommodative stance, and the benchmark rate was left unchanged at a historic low of 4 percent. The status-quo policy outcome was on expected lines despite mounting inflationary concerns. Indira Rajaraman, veteran economist and former director, RBI Central Board, says, "The situation right now is extremely difficult, and one cannot justify a rate cut at all. But, given the uncertainty around the omicron variant, RBI cannot justify a rate hike either."

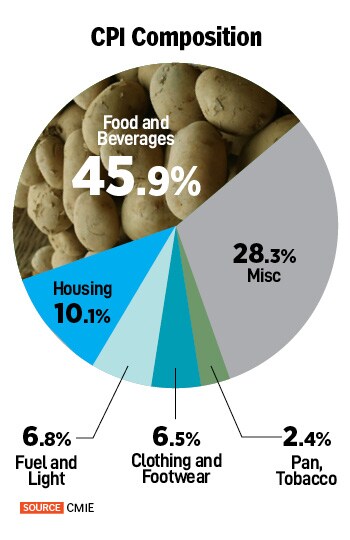

On the face of it, inflation seems to be aligned with the MPC"s target of 4 percent [with a +/- margin of 2 percent]. But many economists are wary of underlying dynamics masking the "real" inflationary pressure, given the overall composition of the consumer price index (CPI) basket [Exhibit 1]. The cost of 131 out of 293 (or 45 percent) low-weightage items in the CPI basket rose by over 6 percent. So, the headline inflation at 4.5 percent in October could have been higher if not for the recent moderation in food prices (which was largely due to statistical reasons), says Madan Sabnavis, chief economist, Care Ratings.

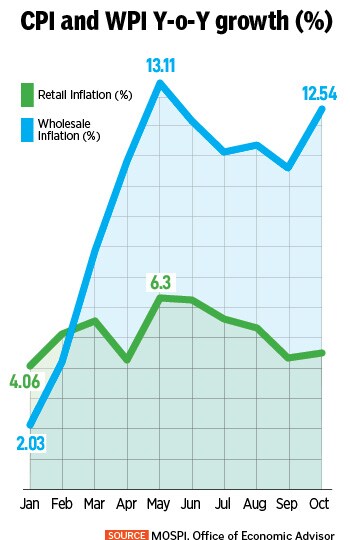

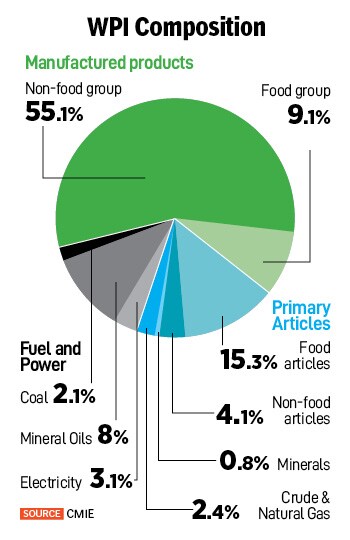

The rise in core inflation—which excludes food and fuel—is a big concern. The central bank largely uses consumer surveys to gauge inflation, and expects CPI or retail inflation to peak at 5.7 percent in the fourth quarter of the current fiscal [Exhibit 2]. But, the wholesale price index (WPI) basket [Exhibit 3]—comprising over 55 percent non-food items—was burning red hot at 12.5 percent in October, and crossed the double-digit barrier for the first time in April [Exhibit 4]. Raghuram Rajan, former RBI governor, had replaced the use of the WPI with the CPI for setting the benchmark rate.

The rise in core inflation—which excludes food and fuel—is a big concern. The central bank largely uses consumer surveys to gauge inflation, and expects CPI or retail inflation to peak at 5.7 percent in the fourth quarter of the current fiscal [Exhibit 2]. But, the wholesale price index (WPI) basket [Exhibit 3]—comprising over 55 percent non-food items—was burning red hot at 12.5 percent in October, and crossed the double-digit barrier for the first time in April [Exhibit 4]. Raghuram Rajan, former RBI governor, had replaced the use of the WPI with the CPI for setting the benchmark rate.

Public finance expert M Govinda Rao, former director, National Institute of Public Finance and Policy, says, "I don"t think this is alarming to policymakers yet even though people are suffering. Earlier such high WPI could have posed a huge challenge for governments." Rao is concerned that a high WPI will significantly stoke the inflationary trend if fiscal measures are not deployed to augment supply of raw materials like coal, since a rate cut does not seem to be on the cards for now. On his part, Das put the ball in the government’s court, suggesting a reduction of excise duty and VAT on petrol and diesel to cool inflation.

The growing gap between the CPI and WPI [Exhibit 4] can potentially erode profit margins of small business owners and manufacturers. This can lead to a roll back in production plans and adversely affect economic efficiency, growth and employment. Rising input costs have a spiralling effect and can derail the growth momentum if unchecked. Das alluded to this when he said, "Persistence of high core inflation since June 2020 is an area of policy concern. Input cost pressures could rapidly be transmitted to retail inflation as demand strengthens."

The RBI has retained its GDP and inflation projections at 9.5 percent and 5.3 percent respectively for FY22 [Exhibit 5]. But Aurodeep Nandi, economist and VP at Nomura, believes the central bank"s macro view of the economy "somewhat downplays the inherent upside risks on inflation, especially with firms across various sectors starting to raise their prices amid potential demand side pressures that would start to build up as the output gap closes".

To be sure there are several factors in play that could considerably push inflation in the coming months, and RBI"s projection of inflation peaking in March could be optimistic at this point. For example, with state elections round the corner, there is the likelihood of populist measures, like an increase in minimum support prices (MSP) which could add to inflation woes. Similarly, telecom companies have hiked or are looking to hike tariffs to boost ARPUs (average revenue per user), and this could potentially offset any benefits from duty reductions on oil. In fact, Nandi sees room for a rate hike of 100 basis points in calendar year 2022.

To be sure there are several factors in play that could considerably push inflation in the coming months, and RBI"s projection of inflation peaking in March could be optimistic at this point. For example, with state elections round the corner, there is the likelihood of populist measures, like an increase in minimum support prices (MSP) which could add to inflation woes. Similarly, telecom companies have hiked or are looking to hike tariffs to boost ARPUs (average revenue per user), and this could potentially offset any benefits from duty reductions on oil. In fact, Nandi sees room for a rate hike of 100 basis points in calendar year 2022.

However, the RBI MPC has clearly reiterated its stated mission to support growth and "normalise liquidity conditions when warranted" in a "non-disruptive way". Though rising inflation poses a threat to sustainable macro objectives, since economic growth is still not durable [Exhibit 5], the central bank is likely to focus on measures to support growth and not hike rates or change its dovish stance this fiscal, explains Sabnavis.

Importantly, the US Federal Reserve recently signalled a shift in monetary policy to address surging inflation despite the threat posed by the new Covid variant omicron. Should the US Fed taper its balance sheet sooner than expected, there can be fresh challenges for the domestic economy in the form of "spillovers". "In such a scenario, domestic macro fundamentals need to be resilient, with appropriate policy stances and actions, and strong buffer," said Das.

There has been some “fine-tuning" as the RBI governor elaborated a 14-day VRRR (Variable Rate Reverse Repo) auction as the primary mode to mop up excess liquidity from January 1, 2022. This is in addition to tools like OMOs (Open Market Operations) to manage liquidity operations. In essence, this is as effective as a reverse repo hike, according to market participants. They see this in line with the central bank’s objective “to ensure that financial conditions are rebalanced in a systemic, calibrated and well-telegraphed manner while preventing build-up of financial stability risks."

There has been some “fine-tuning" as the RBI governor elaborated a 14-day VRRR (Variable Rate Reverse Repo) auction as the primary mode to mop up excess liquidity from January 1, 2022. This is in addition to tools like OMOs (Open Market Operations) to manage liquidity operations. In essence, this is as effective as a reverse repo hike, according to market participants. They see this in line with the central bank’s objective “to ensure that financial conditions are rebalanced in a systemic, calibrated and well-telegraphed manner while preventing build-up of financial stability risks."

After the MPC announced the bi-monthly credit policy, the stock market ended the trading session in the green, with the S&P BSE Sensex closing over 1016 points higher at 58,649.68 points. Most brokerages do not expect the RBI to hike the repo rate this fiscal. “We expect the RBI MPC to turn neutral in April and hike policy repo rate in June 2022," said BoFA Global Research analysts in a report dated December 8.

Clearly, the focus on nurturing economic recovery overshadows the looming threat of inflation in the background. Worldwide, inflation is no longer seen as a transient pain, yet most central banks, RBI included, are hesitant to err on the hawkish side in this Catch-22 situation. Most economists do not see an alternative monetary policy response to this conundrum either. But they do suggest fiscal measures, such as a cut in high taxes on fuel, to ease the prospect of high inflation and its cascading impact on the economy.

Given the state of the economy, most policymakers see the new coronavirus variant omicron as a bigger source of disruption than inflation, even as they prepare for a ‘soft landing’ in an increasingly volatile economic backdrop. One wonders if this extract from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland resonates with central bankers in these perplexing and unprecedented times:

“In that direction," the Cat said, waving its right paw round, “lives a Hatter: and in that direction," waving the other paw, “lives a March Hare. Visit either you like: they’re both mad."

First Published: Dec 09, 2021, 14:45

Subscribe Now