Can Karbonn mobiles fight back?

After being relegated to the margins, the maker of Karbonn mobiles is back with a four-pronged attack. Will the gambit pay off?

A comeback is always stronger than a setback. It will take time but I am ready to grind it out and be back with a bang: Pardeep Jain, Managing Director, Jaina Group

A comeback is always stronger than a setback. It will take time but I am ready to grind it out and be back with a bang: Pardeep Jain, Managing Director, Jaina Group

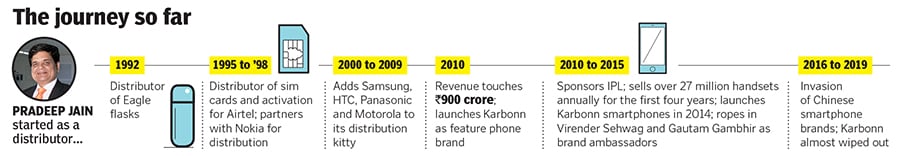

Image: Amit Verma[br]At 52, Ray Kroc was taking the boldest and riskiest bet of his life. After two decades of being a salesman—selling paper cups and milkshake machines—part-time pianist and real estate agent, the plucky American had opened his first McDonald’s franchisee outlet at Des Plaines, Illinois, in 1955. The unlikeliest candidate anybody would hedge money on, Kroc had survived the First World War, and had seen his father amass and lose his fortune in speculation and stocks.

Six years later, in 1961, Kroc went on to buy McDonald’s. “Achievement must be made,” the unflinching entrepreneur wrote in his autobiography Grinding it Out, “against the possibility of failure, against the risk of defeat. Where there is no risk, there can be no pride in achievement, and consequently, no happiness.”

Cut to India. At 50, Pardeep Jain is doing a Kroc. “He has an inspirational story of never giving up in spite of multiple failures,” says the managing director of the Jaina Group, which had hit a high in early 2014 when the maker of the Karbonn mobile cornered a 10 percent market share, making it the third biggest smartphone brand in India.

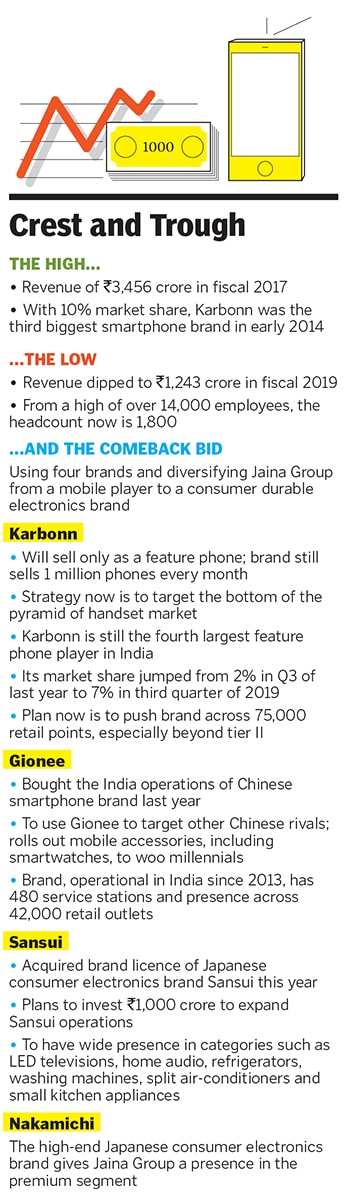

Five years later, fortune has swung to the other end. Karbonn, along with other homegrown handset players like Micromax, Intex and Lava, has been muscled out by Chinese smartphone players such as Xiaomi, Vivo and Oppo. Jaina Group, which boasted of a revenue of ₹3,456 crore in fiscal 2017, hit a new low of ₹1,243 crore two years later. [br]“If Kroc can dream big at 52, so can I at 50,” says Jain, flashing a small red-yellow book cover with golden arches. Grinding it Out not only finds pride of place on Jain’s spacious work station at his corporate office in the industrial area of Okhla in Delhi, but also happens to be the Bible for the intrepid entrepreneur who started his journey in 1992 as a sales distributor. It was only a decade later that he launched Karbonn.

[br]“If Kroc can dream big at 52, so can I at 50,” says Jain, flashing a small red-yellow book cover with golden arches. Grinding it Out not only finds pride of place on Jain’s spacious work station at his corporate office in the industrial area of Okhla in Delhi, but also happens to be the Bible for the intrepid entrepreneur who started his journey in 1992 as a sales distributor. It was only a decade later that he launched Karbonn.

Jain reckons he has reasons to be optimistic. Although Karbonn is no longer a smartphone brand, as a feature phone it clocks sales of 1 million phones every month. “The brand recall is still very high and it is finding wider acceptance at the bottom of the pyramid of the handset market,” says Jain. Karbonn, he points out, is still the fourth largest feature phone player in India. “Market share jumped from 2 percent in the third quarter of last year to 7 percent a year later,” he claims, citing Counterpoint Research numbers.

The smartphone space vacated by Karbonn is being filled by Gionee, the Chinese brand whose India rights Jain bought last year. “So there is a Chinese brand to take on Chinese rivals,” he says, adding that the brand has a retail reach of over 42,000 outlets across India. “While the urban market is crucial, there is a huge untapped market beyond tier II,” he contends.

What Jain is also betting big on is the opportunity that millions of feature phone users provide whenever they upgrade to smartphones. By tying up with Sansui—the Japanese consumer electronics durable label that had been selling in India for three decades with Videocon—Jain is trying to hedge his bets by moving away from phones. Nakamichi, a high-end Japanese electronics player, gives him a play at the premium end of the market. “The four-pronged strategy is well designed to take the group to the next level of growth,” he says.

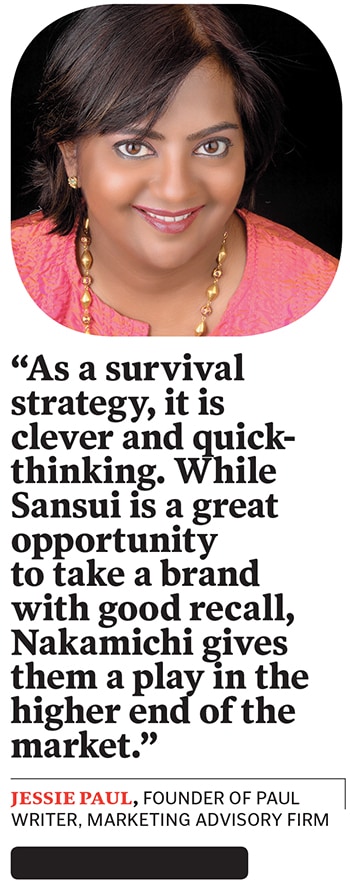

Marketing experts are impressed with the fightback strategy. “Necessity is the mother of invention,” says Jessie Paul, founder of Paul Writer, a marketing advisory firm. The smartphone market, she points out, is no longer conducive to Indian players in any segment, and Jaina Group needs to look elsewhere for survival. While Sansui is a great opportunity to take a brand with good recall and leverage their trade network and manufacturing skills, Nakamichi gives Jaina a play in the higher end of the market. “They have identified the weakness of Videocon as an opportunity and are moving in with a range of similar products,” she says. As a survival strategy, Paul lets on, it is clever and quick-thinking.

Paul lists out the big opportunity that Jaina is gunning for across the product categories. Take, for instance, the refrigerator market which is dominated by a few brands like LG, Samsung, Videocon, Godrej and Whirlpool.

“If they are able to displace Videocon, then they will immediately be among the top few,” she contends. While TV as a category—especially smart TV—is being disrupted by smartphone players like Xiaomi and OnePlus, the opportunity lies in capturing the new, emerging market which is price-sensitive and not brand-conscious. “The Jainas have assumed that their trade networks built from their cellphone business combined with the Sansui brand will be sufficient to win,” she adds.The going, however, might not be a cakewalk. A comeback strategy, avers Deepak Kumar, founder analyst at B&M Nxt, is not easy to thrash out in today’s smartphone market, which is literally divided between Samsung and a small set of Chinese players. There was a time when Indian handset players had successfully captured the handset market in the feature phones era. With the advent of smartphones, the game rapidly changed and Indian players were pushed to the brink of extinction, he underlines. “Jaina Group’s strategy of distributing select smartphone and consumer electronics brands is good but not enough in today’s market dynamics,” maintains Kumar. A lot will depend upon how deep and wide the strategy is, he adds.

What would also come into play is the way the new strategy is executed. For example, it would be crucial to see if Jain is looking at just the individual market segments such as the smartphone and the TV, or if he is looking at a wider smart-screen play. Similarly, it would be worth watching if they are looking at consumer electronics such as TVs, fridges, and washing machines as standalone market opportunities or as an integrated internet-of-things (IoT) play, says Kumar. While a strong distribution network could help push piecemeal products to an extent, it is only a well-knit digital home strategy that could make an initial success repeatable and sustainable, he adds.

Jain, meanwhile, knows that the fightback won’t be easy. But he is not ready to give up. “I am willing to grind it out,” he says. Kroc, it seems, is not only inspiring him to struggle but also making him love the grind.

First Published: Dec 02, 2019, 12:45

Subscribe Now