Rapid testing: Race against time

After a slow start, will India's efforts to ramp up testing for Sars Cov2 or the coronavirus be quick enough?

In India, phone booth or kiosk testing is being actively explored to contain the spread of cornavirus. Kiosks were installed at Ernakulam Medical College in Kerala on April 6

In India, phone booth or kiosk testing is being actively explored to contain the spread of cornavirus. Kiosks were installed at Ernakulam Medical College in Kerala on April 6

Arun Chandrabose / AFP via Getty Image

Until March 20, the only way to get tested for Sars Cov2 in India was if you’d travelled abroad or come in contact with someone who had and reported a fever, cough or difficulty in breathing. And even then it was incredibly hard to get tested.

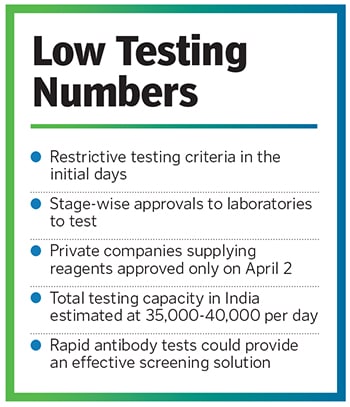

The strict testing definition for a virus that had been declared a pandemic masked the crucial lack of testing capacity. In order to get tested, one had to report to a government facility and have nasal or throat swabs taken. They were sent to the National Institute of Virology in Pune and results were made available two days later. With a testing criteria narrowly restricted to foreign travel, it’s hardly surprising that India had conducted only 13,316 tests by March 20 with 236 testing positive. During March, which would later turn out to be a crucial month, scores of travellers with flu-like symptoms slipped through.

By then the speed of the virus’ spread had taken the world by surprise. Just like in India, the initial low infection rates in Italy, Spain, the UK and US had lulled governments into a false sense of calm. “It was the virulent nature coupled with the long incubation period that allowed the virus to spread unhindered,” says Dr Harish Mahajan, chairman, Center for Advanced Research in Imaging, Neuroscience and Genomics. This was unlike Sars, which took three days to incubate, making it was easier to isolate infected people.

While the government has steadfastly maintained that the lack of testing capacity is not to blame for its decision to restrict the initial rounds of testing, interviews with people who run laboratories and make testing kits suggest that crucial time was lost in February and early March. Had larger numbers been tested (along with stricter quarantines for international travellers), isolation decisions could have been taken earlier. “Our (and the world’s) biggest problem was that we didn’t have a model to follow and so we had to make things up as we went along,” says the founder of a company that has recently received approval for testing kits.

In a situation where every day makes a difference in the infection curve, the steps taken by the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) were incremental. As a result, laboratories are still struggling to get testing kits and deploy them and, while rapid antibody tests have been approved, the earliest deployment is at least a fortnight to a month away. “Our aim is to first stop transmission and flatten the curve,” says Dr Rajni Kant, director, planning and coordination, ICMR, pointing to the fact that its containment strategy hasn’t worked.

Testing Infrastructure

The first reported case of the Sars Cov2 virus on Indian shores was on January 31 when three students returning from its epicentre Wuhan tested positive in Kerala. These were early days in understanding the virus Wuhan had only been locked down a week earlier. The Indian response was limited to cancelling visas of Chinese nationals. Over the course of the next 45 days, airports carried out limited screening on incoming passengers. Samples of suspected cases were sent for testing to Pune.

That changed on March 20 when the speed and geographical spread of the virus increased. In a series of steps, the government progressively widened the definition of "would be tested" and worked on increasing the number of testing laboratories. First, laboratories in state capitals were brought in, then district government hospitals, then private hospitals with laboratories accredited to the National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories (NABL) and finally private diagnostics laboratories. At the time of writing in mid-April, there were 166 government and 70 private laboratories approved by ICMR. R Kailashnath, Managing Director, CPC Diagnostics

R Kailashnath, Managing Director, CPC Diagnostics

But opening up the number of laboratories was only half the battle. There were two other issues that would slow testing. The first was sample collection. Given the highly contagious nature of the virus, lobotomists had to necessarily wear personal protective equipment (PPE) suits, which were in short supply. The swabs had to be transported in refrigerated containers to avoid contamination and be tested only in biosafety level 2 laboratories.

“These restrictions mean that there are only a limited number of laboratories in India that can run the tests,” says Arunima Patel, founder of iGenetic, which has received ICMR approval to test for Sars Cov2. She advocates loosening the restrictions. To avoid the risk of infection (and contamination) for the person collecting samples, innovations like phone booth testing and drive-through testing have been tried out. In India, the phone booth or kiosk testing is being actively explored. Kiosks were installed at Ernakulam Medical College on April 6.

Second, the reagents needed to run the tests arrived slowly. Here’s how the process works. The swabs collected are put through a thermal cycler also known as a PCR machine. Through a process known as reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RTPCR), they amplify the DNA to check for the virus—a process that takes at least six hours.

PCR machines in laboratories across the country needed reagents to check for the virus. These were in short supply. The initial supply was by the government, but the delay in granting approval to reagents made by private companies meant that private hospitals and laboratories were not able to offer the tests till the first week of April. Even then, they had to rely on imports that are also in short supply. Chandra Sekhar Nair, Chief Technical Officer, Molbio

Chandra Sekhar Nair, Chief Technical Officer, Molbio

Two private diagnostic companies and one supplier of reagents told Forbes India that they are only processing between 100 and 200 samples a day. Netmeds, an online pharmacy, has tied up with private laboratories. “The response has been slow partly on account of the costs,” says Jugal Anchalia, vice president, strategy and new initiatives at Netmeds. That is unlikely to change as a recent Supreme Court order has asked private laboratories to provide free testing only for those eligible under the Ayushman Bharat health plan.

The staggering of approvals for laboratories and companies that supply the reagents has meant that India’s testing capacity is still woefully short and will take at least four weeks to expand. The total stock of PCR machines in the country can process 35,000-40,000 samples a day. Private companies are working to increase that number. “My estimate is that processing 100,000 samples a day soon should be possible,” says Chandrasekhar Nair, chief technical officer of Molbio Diagnostics, that received approval for its point of care PCR platform for testing for Sars Cov2. In the meantime, some workarounds are being explored. Samples from areas that have low positivity rates are being pooled. Up to five samples from such areas can be tested at one go. On April 12, the last date for which data is available, India tested 16,002 samples a day, up from 4,346 on March 30.  Antibody tests

Antibody tests

With the limitation in testing capacity apparent, the ICMR on April 4 approved antibody tests on anyone showing ‘influenza like illness’. These serological tests work on a blood sample drawn intravenously. Results are available in 30 minutes. “The key advantage of these tests is that they can be deployed rapidly and you don’t need an expert to perform and interpret results,” says R Kailasnath, managing director at CPC Diagnostics, which has received IMCR approval for its antibody tests.

Here’s how they work. A person infected with Sars Cov2 would start producing antigens to develop antibodies to the virus. These tests have been used successfully for

other viruses like dengue and measles, but with Sars Cov2, the long incubation period introduces a complication. A person may be asymptomatic and say five days after being infected, has still not started producing an antibody. For such a person, the test would produce a false negative and they would slip through. Recognising this, the ICMR has mandated confirmatory PCR tests for positive cases, but advises them also for negative cases where there is suspicion.

Where the antibody tests score are in hotpots, allowing civic bodies to test large number of people quickly and make an assessment about the percentage infection levels in a certain area. The lower accuracy is compensated for by the ease and speed of testing. “We plan to conduct antibody tests to check the proliferation of the virus and also to identify obvious suspects,” says Kiran Dighavkar, assistant commissioner at the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation. State governments plan to roll these tests out in the next month with Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu placing orders for 100,000-300,000 tests.

As the race to contain the virus continues, the real use of antibody tests is likely to come between six and 12 months from now. Once a substantial portion of the population gets infected and recovers, they’d develop antibodies and would be better prepared to handle a second wave of infections. (An important caveat is that we don’t know if and how the virus will mutate over the course of the year.) At that point, rapid testing through point of care antibody kits would allow people to check for immunity. Think of these as point of care tests like a diabetes test or a pregnancy test that could be done at home.

Testing quickly for antibodies could allow authorities to make quick decisions on when to open up or shut down areas as well as allowing individuals back at workplaces and in crowded places. These testing kits, which may work with just a finger prick test are under development and could hold the key to living with the virus as well as being prepared if and when the next one strikes.

First Published: Apr 29, 2020, 10:39

Subscribe Now