Just having completed a rigorous 12-hour shift, Dr Prerna Tayal needs to recoup, and requests that we do the interview later. The 26-year-old is a third-year post-graduate gynaecologist, working as a resident doctor at the Lady Hardinge Medical College in New Delhi. Her shift done, Tayal doffs her personal protective equipment (PPE), sanitises everything, especially her pruney hands, and heads back home.

![prerna tayal b prerna tayal b]() Dr Prerna Tayal is a third-year post-graduate gynaecologist, working as a resident doctor at the Lady Hardinge Medical College in New Delhi

Dr Prerna Tayal is a third-year post-graduate gynaecologist, working as a resident doctor at the Lady Hardinge Medical College in New Delhi

Tayal says it is difficult to calm a labouring woman down, when she is in a lot of pain and distress, while wearing PPE. Moreover, companions are not allowed inside the labour room during the pandemic. “It becomes difficult for us to take the patients’ blood samples as we cannot easily trace the veins, due to the blurry vision through the goggles,” she says.

In these three months of Covid-19 duty, Tayal went through a tough bout of depression. “Things were getting too much and I was having negative thoughts about everything. But I got back to normal with the support from friends and family, who kept reminding me about how I was making everyone proud at a young age,” she recalls. “When I wore PPE gear for the first time, I felt quite motivated but all of it went off after being in it for an hour. I wanted to get rid of it and breathe some fresh air…trust me this is not easy!”

Resident doctors like Tayal are in training to gain a master’s degree or are employed post their bachelor’s in MBBS or other medical field. Each day at work during the pandemic has been like a new battle, much like being sent to war. As the day progresses, the vision becomes blurred, the stomach longs for nutrition and the mind begs for a break. Decision-making becomes difficult. They just wait for day to end, and there comes a new patient admission. The grind restarts.

![dr satish tandale in ppe dr satish tandale in ppe]() Dr Satish Tandale is a third-year PG Resident at Nair Hospital in Mumbai and President of Maharashtra Association of Resident Doctors (MARD)

Dr Satish Tandale is a third-year PG Resident at Nair Hospital in Mumbai and President of Maharashtra Association of Resident Doctors (MARD)

For Dr Satish Tandale, 30, being left behind in his specialisation subject of Pathology is a matter of concern, and at times, one of the reasons for anxiety. “Since almost three months now we’ve stopped working in our specialisation department, unlike at other hospitals where residents are rotating between Covid-19 and non-Covid19 duties. It’s a monumental academic loss for us,” says the third-year PG Resident at Nair Hospital in Mumbai and President of Maharashtra Association of Resident Doctors (MARD). “We do have mental breakdowns at times, due to several reasons. But we console ourselves with the fact that we are needed in this pandemic, and this is a small sacrifice to make. As they say, all’s fair in love and war,” he says.

For resident doctors, their responsibilities include pulling trolleys, shifting patients, drawing blood, taking rounds, presenting patient reports and status to senior doctors, counselling patients who are panicking and also informing patient’s relatives about their current status.

“It gets too much to bear at times, especially when you lose patients despite your efforts, or can’t do anything to help in the first place. The number of patients has been so high that resources are exhausted, and you can’t provide the care that is required. Some patients come so late and in such a bad state that nothing can be done. This causes a lot of mental anguish,” explains Tandale adding that while wearing PPE gear for six to eight straight hours, he loses almost two litres of sweat in each duty, post which he suffers dehydration, muscle pain, cramps and weakness. “I really miss my family but obviously can’t go home,” sighs Tandale, who is from Beed, Maharashtra and lives alone in a Mumbai hostel.

Resident doctors who have just begun their careers also have to deal with angry patients who are unsatisfied with the hospital facilities. For instance, 25-year-old Dr Saurav Kumar, a resident doctor from Lok Nayak Jai Prakash (LNJP) Hospital in New Delhi, says, “There are patients who don’t like the quality of food or any other arrangements, and they take it out on us. I try and empathise but it also mentally affects me—I’m human too. Dealing with a pandemic at the beginning of your career is tough.”

Inadequate quarantine and testing, violence, stigma, low salaries, resource scarcity—these are some of the issues that resident doctors face, even though they form the pillars of most medical institutions, explains Dr Shivaji, President of Federation of Resident Doctors’ Association (FORDA), India.

On condition of anonymity, a resident doctor from Osmania Medical College in Telangana shares some every day stories: “This pandemic has taught me more life lessons than subject matter. For one, we are being trained to become insensitive to pain and death. There’s little value of life when it comes to the underprivileged. I know we don’t have great health infrastructure but we’re not even utilising what is already available wisely.”

Poor people who don’t have the money for treatment are sent to isolation wards and left there—and without any treatment, resident doctors are asked to inform their families of their demise. “I really feel sad for the patients who come here with a hope for tertiary care...I say this with tears in my eyes…’No….we’re not doing total justice to many of the helpless patients coming here."”

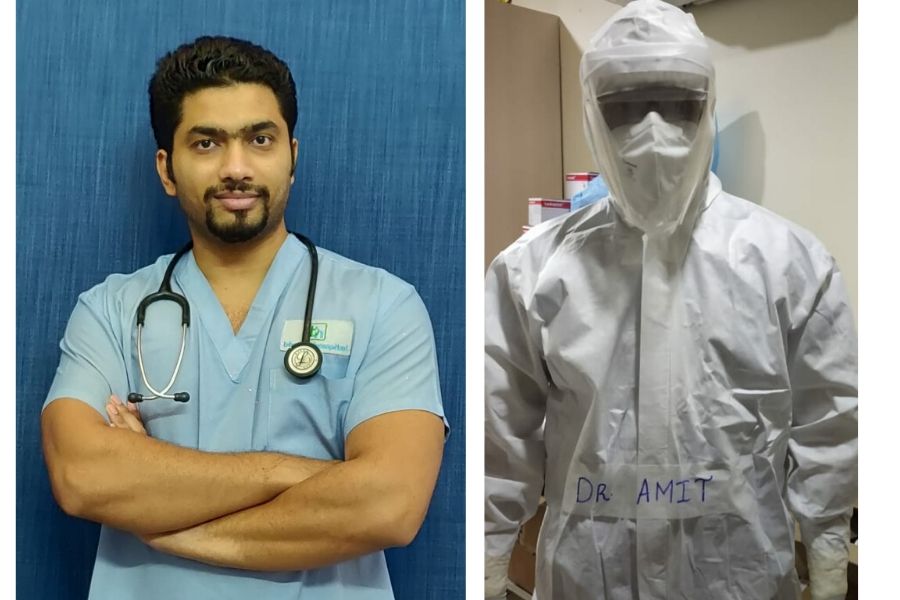

![dr amit dr amit]() Dr Amit Dhekane tested positive for Covid-19 and was hospitalised for 18 days, but got back to the battlefield soon after

Dr Amit Dhekane tested positive for Covid-19 and was hospitalised for 18 days, but got back to the battlefield soon after

Dr Amit Dhekane, a senior intensivist at Bhatia Hospital in Mumbai is pursuing an Indian Diploma in Critical Care Medicine (IDCCM). Due to a stressful work schedule, it becomes difficult for him to prepare for his final exams, which are coming up in two weeks. “The hospital does pay well in terms of incentives, but we are here at the cost of family life,” says Dhekane, who has been away from his family for three months.

Dhekane has to deal with very critical Covid-19 patients each day—even after taking precautions, he tested positive for Covid-19 and was hospitalised for 18 days, but got back to the battlefield soon after. “We have two teams working in rotation—work seven days, with seven days off. In our off period, we are still helping colleagues who are suffering from Covid-19,” he says.

Hospitals, meanwhile, say they can’t do without resident doctors. “Resident doctors are the most vital cog in the organized machine of a hospital,” says Dr Jeenam Shah, a consultant pulmonologist dealing with Covid-19 patients. “Without them, the entire system will crumble. Without recognition, they are working in extreme conditions, holding fort and protecting our community from the deadly virus. I salute them.”

A group of residents doctors at Lady Hardinge Medical College in New Delhi

A group of residents doctors at Lady Hardinge Medical College in New Delhi Dr Prerna Tayal is a third-year post-graduate gynaecologist, working as a resident doctor at the Lady Hardinge Medical College in New Delhi

Dr Prerna Tayal is a third-year post-graduate gynaecologist, working as a resident doctor at the Lady Hardinge Medical College in New Delhi Dr Satish Tandale is a third-year PG Resident at Nair Hospital in Mumbai and President of Maharashtra Association of Resident Doctors (MARD)

Dr Satish Tandale is a third-year PG Resident at Nair Hospital in Mumbai and President of Maharashtra Association of Resident Doctors (MARD)