Aspirations, which belie the difficult realities of their lives, and those of most of their peers at the school, where 70 percent students belong to migrant families. Their parents are daily-wage earners, construction workers, ragpickers or domestic helpers with an average monthly income of less than ₹15,000. Almost 60 percent of Renuka’s friends have either never been to school before, or had been out of school before rejoining.

When the pandemic hit a year ago in March, Rehana’s father, a construction worker, lost his livelihood and decided to migrate to his hometown in Gulbarga temporarily before returning to Bengaluru. By May, the school procured smartphones through a community donation drive. Teachers started sharing lessons through WhatsApp, conducting reading sessions and one-on-one training over phone calls. Parents were required to come in at least once a week to school to collect worksheets and library books.

But there were other challenges. Renuka, for instance, is the eldest of three siblings. Her mother, a domestic help, and her father, a helper to a truck driver, were at home through most of last year. This meant that when Renuka sat down to study, having five people in the same small room made it impossible for her to concentrate.

Their teacher Parvati, who has been with the RG Halli government school since 1995, tells Forbes India that she struggled to get students to study online. “I sent lessons over on WhatsApp, but so many parents did not even download the files,” she says, adding that some parents took their children out of school to make them work in menial jobs, and a few others continued only for the sake of mid-day meals. School for classes 6 and above restarted in January. “I am happy to come back to school because I just could not study at home, and could not meet my friends either,” says Renuka.![chengalpet district school teacher chengalpet district school teacher]() K Kamakshi and V Sumathi, teachers at a government school in Chengalpet, Tamil Nadu, say once children started working, they were not interested in studies

K Kamakshi and V Sumathi, teachers at a government school in Chengalpet, Tamil Nadu, say once children started working, they were not interested in studies

Image: Infant J[br] Such challenges exist even in a school like RG Halli where the government receives a good share of community support. The school was adopted by citizen’s volunteer group Whitefield Ready in 2008. In 2019, English-medium classrooms were launched—through a public-private partnership model involving the Karnataka government, non-profit Teach for India and Inventure Academy—for children of migrant workers from Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and West Bengal who could not understand Kannada, says Sumedha Rao, a lead volunteer with Whitefield Ready.

When the lockdowns were announced, with support from the R₹otary Bangalore IT Corridor and the local community, volunteers organised rations, medical support and even house rents to prevent parents from migrating away and pulling their kids out of the RG Halli school. They also reached out to startups and corporates to collect refurbished digital devices and internet support for children to continue studying with the least amount of disruptions.

Many other government or low-income private schools had to work with far fewer resources and support systems. GH Renukaraj, who teaches classes 8 to 10 in the Arsikere government school in the Pavagada taluk of Karnataka, tells Forbes India that over 90 percent of the 117 students in his school are children of landless farmers. Only half those kids have access to digital devices. “When school resumed, the learning gap was so huge that 80 percent of students had forgotten basic math like multiplication and division, science concepts and writing skills,” he says. “We had to teach them all that again, plus cover the entire year’s syllabus in a matter of five months. Teachers worked additional hours to ensure children do not miss out.”

![smartphone access smartphone access]()

In the Urmal village in Jharkhand, only 10 percent of the 250-odd children in the local school had access to smartphones for study materials sent over via WhatsApp. So teachers printed worksheets for all students and went door to door to deliver them. They would then collect them back and make assessments within a week. To ensure students didn’t drop out and more enrolled despite the pandemic, teachers went to each individual home to speak with parents.

“Most people in this village are illiterate farmers or landless labourers who are not very involved with their kids’ education. We have to incentivise them through mid-day meals, clean uniforms and free books to ensure they keep their children enrolled in school,” science teacher Subhash Chandra tells Forbes India. He adds that during the lockdown, the government had telecast classes and lessons on Doordarshan for students who did not have access to smartphones. “But sometimes there was no electricity supply, so how will they watch lessons on TV?”![digital educatiojn digital educatiojn]() Do the Math

Do the Math

The pandemic resulted in an obscene boom for startups operating in India’s edtech space. These startups raised a total investment of $2.22 billion in 2020, as compared to $553 million in 2019, according to a report titled ‘The Great Un-Lockdown: Indian Edtech’ by Indian Private Equity and Venture Capital Association and PGA Labs. At least 92 startups attracted funding last year, out of which 61 received seed funding. Online education platforms, the report says, had raised $4 billion between 2016 and 2020. Put these figures against the statistics of children struggling to access basic forms of digital education, and the disparity appears as stark as ever.

Union Education Minister Ramesh Pokhriyal said in Parliament in September 2020 that India has over 14 lakh schools. This includes more than 10 lakh government schools that cater to over 60 percent of India’s 32 crore-odd student population. In the wake of the pandemic in March 2020, all schools were forced to go online without warning. As a result, many children were left out of the learning process, mainly due to lack of access to digital devices.

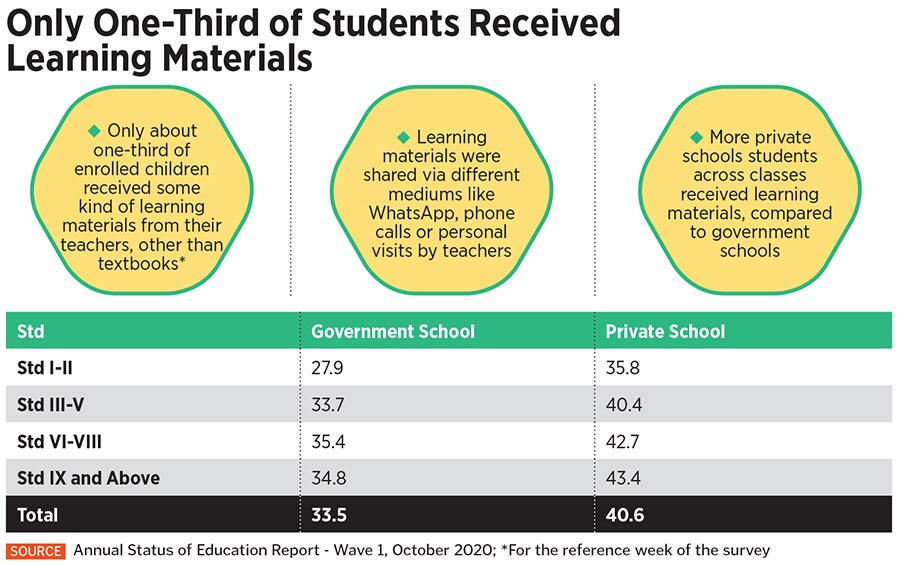

The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER)—Wave 1 facilitated by non-profit Pratham in October 2020 revealed that about 43.5 percent of children in government schools had no access to smartphones. Other than textbooks, only about a third of students received learning materials through mediums like WhatsApp, phone calls, recorded videos or online classes.

“While 35 percent children received learning materials other than textbooks, 70 percent did some kind of learning activity in the reference week. Very few children could participate in live online classes, which was the closest thing to instruction during this period when schools were closed. So there again, you are going to have equity issues,” says Wilima Wadhwa, director of ASER Centre.

She says that states with high learning outcomes performed better in terms of distributing materials to children. As per the report, in states like Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, only 21.5 percent, 21 percent and 7.7 percent children respectively had received learning materials.

Rukmini Banerji, CEO of Pratham Education Foundation, points out that for children to be able to access online classes, schools have to send out lessons on time. As per the ASER 2020 report, 68 percent of parents say that schools did not send learning materials. “Tracking what school systems send to children on an ongoing basis online is also to be taken into account.”

![rural india rural india]()

The field research group at the Azim Premji Foundation undertook a study in September 2020 across 1,522 schools in five states, covering 80,000 children from disadvantaged backgrounds. They found that more than 60 percent of students could not access digital learning for reasons including “absence of a smartphone, multiple siblings sharing a smartphone, difficulty in using apps for online learning etc.”. Over 90 percent teachers in these schools said no consequential assessment of a child’s learning was possible online, while 70 percent of parents felt digital education was not at all effective in helping their children learn.

Even though the government introduced a New Education Policy (NEP) last year, budgets have been slashed. The total budget allocation towards education for FY22 reduced to ₹93,224 crore from ₹99,300 crore last year. E-learning programmes also did not particularly receive a financial boost. “It is a tall ask for the government to make sure every child has access to digital education, but looking at the Union Budget, education is surely not the topmost priority of the government,” says Pramod Sridharamurthy, secretary, India Literacy Project (ILP).

The education non-profit equips teachers like Renukaraj and Subhash Chandra with digital content and visual aids to engage with children more effectively. They have reached over 8.73 lakh underprivileged students across 5,659 remote villages in seven states.

Sridharamurthy adds TV and radio programmes scheduled by the government provided some amount of learning to children, but it was largely a one-sided effort. “Teachers then started conducting classes in small groups of 5-10 kids in open spaces. They carried their laptops loaded with digital content and our low-cost science kits to engage with students,” he explains.![aurangabad aurangabad]() Savita Gajanan Irshid, a nurse from Harsul, Aurangabad, used an app by Rocket Learning to homeschool her three-year-old daughter Aaradhna during the pandemic[br]V Sumathi and K Kamakshi, teachers at a government high school in the Chengalpet district of Tamil Nadu, say these kits and digital aids help them keep children interested in studies. “Many children had no support from family towards academics. Parents sent them to work during the lockdown, because of which the kids were not interested in coming back to school,” Sumathi explains, adding that they have to constantly assuage the fears of many bright students who are worried this learning gap will affect their career or job prospects going forward.

Savita Gajanan Irshid, a nurse from Harsul, Aurangabad, used an app by Rocket Learning to homeschool her three-year-old daughter Aaradhna during the pandemic[br]V Sumathi and K Kamakshi, teachers at a government high school in the Chengalpet district of Tamil Nadu, say these kits and digital aids help them keep children interested in studies. “Many children had no support from family towards academics. Parents sent them to work during the lockdown, because of which the kids were not interested in coming back to school,” Sumathi explains, adding that they have to constantly assuage the fears of many bright students who are worried this learning gap will affect their career or job prospects going forward.

The ASER 2020 report reveals that close to 75 percent children received support from their families in the past year. Among children whose parents had studied only up to class 5 or less, this was lower at 55 percent. Banerji of Pratham says various state governments have also taken initiatives to involve the community in helping underserved children. “In Chhattisgarh, you have mohalla classes. Odisha has a Mo School campaign where alumni volunteer to work with kids during summer holidays. In Nagpur, Maharashtra, Pratham has a radio programme in collaboration with the state government called Shale Baherchi Shala [A School Outside A School] where we see the local panchayats mobilise communities to help children do the programmes the show talks about.” According to her, there is a lot of potential to use various mediums to help underprivileged kids, and edtech companies can certainly chip in to undertake research in this space.

“Edtech for low-income communities usually involves bite-sized content in regional languages that can be grasped even by parents who are not very educated, where you help them engage with and teach children using simple household items instead of fancy toys or gadgets,” says Azeez Gupta, founder of edtech non-profit Rocket Learning that provides foundational education for children up to eight years of age.

Savita Gajanan Irshid, a nurse from Harsul, Aurangabad, wanted her three-year-old daughter Aaradhna to learn basic concepts like addition, subtraction, colours etc. but had to homeschool her due to the pandemic. “The app [by Rocket Learning] helps her understand concepts in a way that she finds fun, and we are required to upload videos of all her assignments and lessons, so it keeps us accountable for her learning as well,” she says. “It’s a good thing we have technology available at home, so we don’t have to worry about our child missing out on school.”

Rocket Learning currently works in Maharashtra, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana, reaching 100,000 children, and around 8,000 teachers. The content is provided in Hindi and Marathi. The startup collaborates with the state governments to enable school and anganwadi teachers to set up WhatsApp groups for their classes. Since the onboarding is done via the government, parents respond to it more seriously.

The non-profit operates close to 10,000 WhatsApp groups, where its artificial intelligence delivers interactive digital content, gamified learning, nudges to remind parents of assignments, regular report cards, and video compilations showing their child’s progress. “Efforts for these children have to be different from typical edtech interventions that we see in upper middle class homes where you have a kid in front of a computer who is motivated enough to study,” explains Gupta. “We also use real-time data to give feedback to the government on which block or district is doing well and which is not, so efforts could be shaped accordingly.”

Nooraine Fazal, co-founder of Inventure Academy, agrees that while it is easy to put curriculum online, learning needs to “have a social context, as per the needs and pace of the learners”. She wants to build the RG Halli school—where enrolments have increased from less than 200 in 2018 to over 450 today—as an example of how collaborating with the private sector can help raise the bar for government schools in the remotest of areas. As part of this, the team is working to put out an open-source learning curriculum that can be used by non-profits, governments or other stakeholders to scale up efforts in public or low-income private schools.

Will Edtech Giants Look This Way?

A few large edtech companies have started approaching rural India as a potential market for their offerings, which might see them put a fraction of their resources into addressing critical access issues. upGrad, the online higher education startup, intends to make an investment of around ₹100 crore over the next two years to develop online programmes for learners spread across remote regions, particularly from a competitive exam preparation standpoint.

Arjun Mohan, CEO-India, upGrad, says people in rural areas always saw more merit in earning a livelihood than spending that time in earning a college degree. But online education has made it more flexible for them to get degrees from the best universities while continuing to earn. “Even companies are more open to hiring people with online degrees now. So we want to take our programmes to people who have restricted access to technology and then connect them to recruiters too. This will help people see that they can study without losing their livelihood and do better in life.” The startup plans to work with local partners from rural communities in order to instil trust in parents and students.

Edtech leader Byju’s has not yet considered rural India as a market, but about 65 percent of its 80 million students and over 5.2 million annual paid subscribers come from outside the top 10 cities, says co-founder Divya Gokulnath. “The internet is making education a level playing field. We understand the inequities in the digital world and want to give children access to lessons irrespective of economic status or geographies.” Byju’s, which opened out the app for everybody during the lockdown, launched its social initiative called Education For All around last November. Its Give Initiative, launched in February, involves people donating old devices for Byju’s to load their courses for free in English or regional languages.

“We have tie-ups with over 40 NGOs working with children across 22 states. It is easier to equip a student with a learning device than build a school with good teachers in it,” says Gokulnath, declining to give numbers on the number of devices collected so far. “Edtech providers can come up with solutions that can go to the remotest part of the country… governments can come forward to set up smart classrooms. Companies can start thinking how they can help teachers and students come online seamlessly. One step in the right direction from every stakeholder can take edtech forward to those who really need it.”

According to Gokulnath, government schools usually have children with different knowledge levels in the same grade. Edtech can help deal with that problem more easily because the content can be personalised and adapted to the child’s pace, she says. “We want to create effective, sustainable and economic models for hybrid learning, reach 5 million students by 2025 and make an impact on the way they learn.”

Banerji of Pratham says we need to invest more in gathering data around children’s learning, so that we can move forward in an evidence-based manner. “When we say children can be helped through digital means and we are concerned about equity, we must have ways to measure these things.”

Students at the RG Halli government school in Bengaluru, mostly children of migrant labourers, farmers and daily wage earners, had challenges accessing digital education in the wake of the pandemic

Students at the RG Halli government school in Bengaluru, mostly children of migrant labourers, farmers and daily wage earners, had challenges accessing digital education in the wake of the pandemic K Kamakshi and V Sumathi, teachers at a government school in Chengalpet, Tamil Nadu, say once children started working, they were not interested in studies

K Kamakshi and V Sumathi, teachers at a government school in Chengalpet, Tamil Nadu, say once children started working, they were not interested in studies

Do the Math

Do the Math

Savita Gajanan Irshid, a nurse from Harsul, Aurangabad, used an app by Rocket Learning to homeschool her three-year-old daughter Aaradhna during the pandemic[br]V Sumathi and K Kamakshi, teachers at a government high school in the Chengalpet district of Tamil Nadu, say these kits and digital aids help them keep children interested in studies. “Many children had no support from family towards academics. Parents sent them to work during the lockdown, because of which the kids were not interested in coming back to school,” Sumathi explains, adding that they have to constantly assuage the fears of many bright students who are worried this learning gap will affect their career or job prospects going forward.

Savita Gajanan Irshid, a nurse from Harsul, Aurangabad, used an app by Rocket Learning to homeschool her three-year-old daughter Aaradhna during the pandemic[br]V Sumathi and K Kamakshi, teachers at a government high school in the Chengalpet district of Tamil Nadu, say these kits and digital aids help them keep children interested in studies. “Many children had no support from family towards academics. Parents sent them to work during the lockdown, because of which the kids were not interested in coming back to school,” Sumathi explains, adding that they have to constantly assuage the fears of many bright students who are worried this learning gap will affect their career or job prospects going forward.