Apollo Tyres: Treading firmly

How the Kanwars of Apollo Tyres built India's most global tyre maker

Onkar (seated) and Neeraj Kanwar choose to move on from their setbacks and focus on growth

Onkar (seated) and Neeraj Kanwar choose to move on from their setbacks and focus on growth

In the long run, successful entrepreneurs rarely look back and brood over what went wrong. Ask Onkar and Neeraj Kanwar, the father-son duo that run Apollo Tyres about the $6 billion in sales target they had set for the company in 2011 and you get a crisp, “That was put aside after the Cooper [Tire] deal didn’t go through.” Neeraj hastens to add that he doesn’t think about the failed deal anymore. Ask them about their exit from the South Africa market in 2013, eight years after paying ₹290 crore for the Dunlop brand and Neeraj says, “I don’t see it as a disappointment, I see it as a learning curve.”

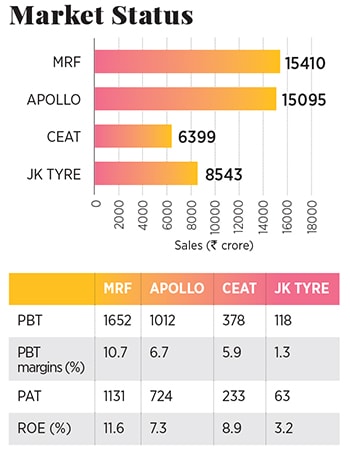

While a five-year financial snapshot doesn’t present a rosy picture, the Kanwars put that down to investments made for future growth. In the last five years sales have been flat, rising 0.8 percent a year to ₹15,095 crore. In the same period, profit fell to ₹724 crore from ₹1,011 crore with a return on equity of 7.3 percent. With investments—a new plant each in Europe and India and a research and development centre in Germany—in place Neeraj, 47, is convinced that the company is on the path to sustained, rapid growth. “Our return on equity will improve going forward,” he says. For now the market has bought his explanation. Despite lower profitability there has been no significant derating on the stock.

Onkar, 77, who nursed a sick company back to health says, “You don’t need money (or incentives from the government). You need an environment to facilitate growth.” Within the company there is a belief that they’ve entered a virtuous cycle of growth that should play out over the next five years. In India the company has a 30 percent market share in the commercial vehicle space and a 25 percent share of the market for passenger car tyres. A 2016 entry into two-wheeler tyres in the Indian market has been well received, with a 5 percent market share. And Apollo has taken measured steps in building a premium brand in Europe with the acquisition of the Verdestein brand.

Gaining Traction

April 2016 was Apollo’s European coming out party. A large contingent of company officials and dealers descended on Budapest for the inauguration of Apollo’s sixth global manufacturing facility. Clearly the company was confident of demand for its Verdestein brand in Europe, which it had positioned as a premium brand. “From being a replacement market-focussed company in Europe, we will soon be starting supplies to leading OEMs in Europe,” said Onkar at the ceremony for &euro475 million plant, which had a capacity of 5.5 million car and 675,000 truck tyres a year. They’d even received their first orders from the Volkswagen Group and Ford.

Getting there had been long and arduous, but the ultimately satisfying journey started with the failed buyout of Dunlop’s South African business in 2006. While the business had initially done well, things went south after the 2010 football World Cup. Electricity rates rose sharply and cheap Chinese imports caused a lot of pain for domestic manufacturers. Labour costs rose to 28 percent versus 16 percent in Europe, 6 percent in India and 3 percent in China. Apollo’s buyout terms meant that they could only sell the Dunlop brand in Africa. The company gradually came around to the view that it wasn’t prudent to invest in a brand that they couldn’t take global. In 2013, they ended up selling business to Sumitomo Rubber that had global right to the brand.

These learnings were put to test when the opportunity for Verdestein came up. Neeraj and Sunam Sarkar, chief business officer at Apollo Tyres, had visited the plant in the Netherlands in 2002 and were impressed with its technological prowess. Verdestein’s acquisition would neatly dovetail into Apollo’s stated objectives of globalising, being technologically self-sufficient and training their personnel. When the opportunity to acquire the company came in 2009 the Kanwars lapped it up for an undisclosed sum.

In the first 100 days Apollo set about utilising Verdestein’s best talent. An R&D centre was set up in the Netherlands and work began on snow tyres for the European market and making tyres that last 100,000 km on Indian roads.

The Kanwars also decided to back their new brand with advertising through tie-ups with European football clubs, such as a deal with Manchester United. “As the European market is oversupplied it becomes critical to be seen,” says Sarkar. (Apollo has started advertising in the Indian Super League and has a higher brand recall than MRF, according to a study by Brand Finance.)

While Apollo has a small market share, of 2 to 3 percent, in Europe, it has got orders from the Volkswagen Group, a validation for the company. This should also allow Apollo to increase its aftermarket share, as car buyers tend to stick to the same brand while replacing tyres. Apollo has also worked with trade magazines to showcase tyres, like one that runs at speeds of 320 kmph, and acquired Reifencom, a German tyre distributor. Despite a small market share, volume numbers in Europea are large and, at ₹4,629 crore in 2018, it accounted for almost a third of revenue.

The Indian market has also proved to be a happy hunting ground. Apollo in the last five years has closed the perception gap with MRF. While MRF is still the market leader and is able to command better pricing, Apollo has worked steadily with dealers to make sure that it gains an increasing share of the aftermarket. Its early bet on radialisation of commercial vehicle and later passenger car tyres paid off and it now sells 500,000 tyres to car makers a month. Plans include a dual brand strategy where Verdestein tyres would be sold as a premium brand in India.

“One sign of the growing confidence in our customers is the fact that they have started putting our tyres on export models as well. In the past they would stick to global brands like Bridgestone for the models they exported,” says Satish Sharma, president, Asia, Middle East and Africa at Apollo Tyres. Completing its brand offering the company has also entered the two-wheeler space in 2016. Here too it decided to make use of a superior technology proposition and launch radials. “We realised we couldn’t be the nth brand in this segment,” says Sharma.

Future Course

After five years of flat topline growth, the first nine months of financial year 2018-19 have seen Apollo Tyres get back in the growth groove. Revenues were up 20 percent to ₹9,292 crore and profit rose 22 percent to ₹486 crore. Most major capital investments are in place including a recently laid foundation for a fifth plant in Andhra Pradesh and a capacity expansion at the Chennai plant. The reduction in Chinese imports on account of an anti-dumping duty has also helped. Neeraj Kanwar has been quoted as saying the company plans to make an attempt dethrone MRF by 2020.

In the last year Apollo has also seen controversy over Neeraj’s pay whose salary rose 42 percent to ₹42.75 crore even as profits fell 34 percent to ₹724 crore. Minority shareholders joined hands to defeat the resolution at the annual general meeting. The Kanwars who own 40.8 percent of the company had no option but to back down. The issue was finally settled after the promoters agreed to take a 30 percent pay cut. Both father and son will now have their salaries capped at 7.5 percent of profit before tax.

The Kanwars see themselves as owner-managers and argue that they deserve a fair compensation in addition to the dividend income they draw from the company. When asked about the flak he received Neeraj argues that the tyre industry is capital intensive and so it takes a few years for investments to reap their benefits. Still he agrees, “It is a learning,” and could have been handled better. As for future growth and revenue targets, “We’re working on our Vision 2025,” is all he is willing to let on.

First Published: Feb 21, 2019, 14:21

Subscribe Now