Can New York's High Line be replicated in India?

As The High Line turns 10, we take a walk down the iconic park and ponder the possibilities

The High Line is one of a handful of elevated green spaces across the world, created out of an abandoned railway line

The High Line is one of a handful of elevated green spaces across the world, created out of an abandoned railway line

Images: Shutterstock

The city of New York has been abuzz about the recent facelift of the Hudson Yards district, with the mysterious and massive Vessel installation at its centre. Designed by London-based Thomas Heatherwick, it is a climbable and interactive monument that was opened to the public this March. Another landmark in the same neighbourhood has quietly reached a significant anniversary: It is ten years since The High Line was opened to the public. In this past decade, the park has become a hot favourite among both residents and visitors to the city that boasts the likes of Central Park and Brooklyn Botanical Gardens.

On a spring morning, I met up with Mary Hannah of Urban Adventures for a walking tour of The High Line that welcomes 8 million visitors every year. What started off as a gentle breeze from the Hudson river nearby, turned into a frosty gale by the time we climbed up the steps. After all, the park is 30 feet above the ground, and seemed to have its own weather patterns.

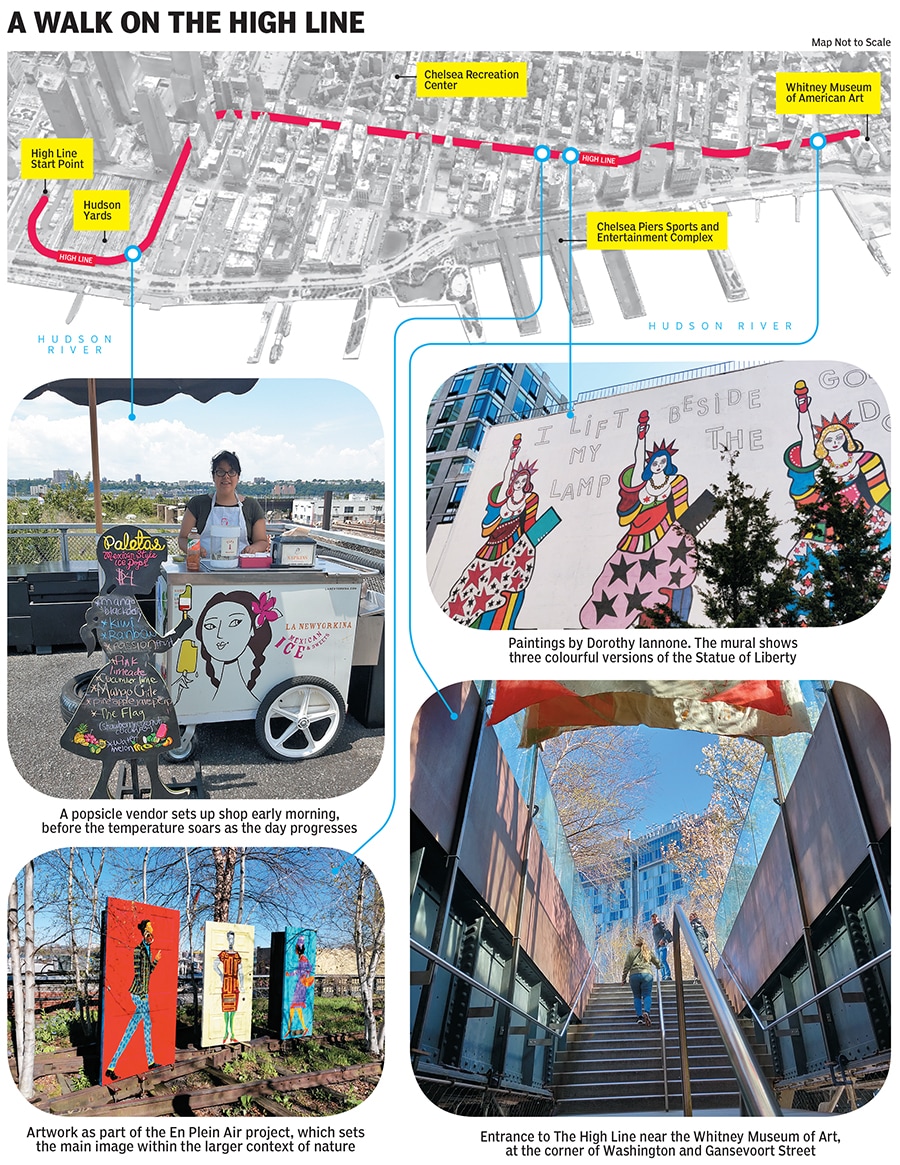

Although it was early morning, there were groups of tourists all along its 1.45-mile length, taking selfies and photographs in front of wildflowers growing in gay abandon and the cheery art pop-ups along the sides. The latter is part of High Line Art, the public art programme that commissions artwork and installations based on specific themes that change frequently and are aimed at sparking debate.

When I visited, the En Plein Air project had just been commissioned and a range of paintings by international artists greeted us. The project is a nod to the French method of painting outdoors (“in the open air”) that sets the main image within the larger context of nature. Further down the track was ‘I Lift My Lamp Beside the Golden Door’ by Dorothy Iannone, an American artist now living in Berlin. Supremely relevant to these times, the mural shows three colourful versions of the Statue of Liberty, with the words running between them, the final line from ‘The New Colossus’, Emma Lazarus’s poem about how America is the promised land for immigrants the evocative lines immortalised in bronze on the original statue.

Down below, New York carried on as usual, with traffic on the streets and coffee shops doing brisk business. But none of that noise or frenzy touched the mood up at the park it was a cocoon, a quiet haven in the middle of the urban chaos. The park is 30 feet above the ground and down below, New York carries on as usual with traffic on the streets[br]The High Line is one of a handful of elevated green spaces across the world, created out of an abandoned railway line that transported goods to and from the Meatpacking District from the 1930s onwards for a few decades. It had to be raised to such a height because of the frequent accidents on the road that was initially used by horse carriages, motor cars and trains. Things got so bad that 10th Avenue began to be called Death Avenue, and a man rode on a horse—the Westside Cowboy, as he was known—in front of the trains, waving a red flag to warn pedestrians and other vehicles.

The park is 30 feet above the ground and down below, New York carries on as usual with traffic on the streets[br]The High Line is one of a handful of elevated green spaces across the world, created out of an abandoned railway line that transported goods to and from the Meatpacking District from the 1930s onwards for a few decades. It had to be raised to such a height because of the frequent accidents on the road that was initially used by horse carriages, motor cars and trains. Things got so bad that 10th Avenue began to be called Death Avenue, and a man rode on a horse—the Westside Cowboy, as he was known—in front of the trains, waving a red flag to warn pedestrians and other vehicles.

But soon after the last train had run its route in 1980 (with freight transportation moving to trucks), these tracks were abandoned and fell into decay, along with much of the surrounding area. Friends of the High Line, a community residents’ group, came to the rescue nearly two decades later, in 1999, and began a fight to preserve and repurpose the space into something useful and even beautiful. As it was, most of the city was not even aware of this piece of potential paradise until the two founders of Friends of the High Line, writer Joshua David and artist Robert Hammond, along with fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg (who still has prominent retail space right below the park) put together a collection of photographs to showcase The High Line across seasons. According to my tour guide Hannah, even the most sceptical New Yorker was taken aback by the flowers that bloomed and birds that nested in the midst of the ruin. Thus, the fate of the space was decided.

In 2003, the city authorities ran a contest inviting ideas to transform the abandoned railway line into a public space, and received hundreds of ideas, including some wild ones of a mile-long swimming pool and a roller coaster. The winning idea came from landscape architect James Corner, who was invited along with design studio Diller Scofidio + Renfro and planting designer Piet Oudolf to work on the derelict space. Wildflowers and dense shrubs are common on the 1.45-mile stretch[br]It is 10 years now since The High Line was opened on June 8, 2009, to great outpouring of praise from New Yorkers, with the New York Times saying, “A subtle play between contemporary and historical design, industrial decay and natural beauty sets the tone”. The decay has not all been removed or hidden away, with enough remnants of rail line’s history scattered along the park, including train tracks upon which flowering plants and dense shrubs have grown. When we came across a couple stretched out on wooden lounge chairs, Hannah explained that the chairs were made from wooden train sidings and still stood on the old wheels of coaches. Friends of High Line, the non-profit conservancy, works with New York’s Department of Parks and Recreation to keep it up and running.

Wildflowers and dense shrubs are common on the 1.45-mile stretch[br]It is 10 years now since The High Line was opened on June 8, 2009, to great outpouring of praise from New Yorkers, with the New York Times saying, “A subtle play between contemporary and historical design, industrial decay and natural beauty sets the tone”. The decay has not all been removed or hidden away, with enough remnants of rail line’s history scattered along the park, including train tracks upon which flowering plants and dense shrubs have grown. When we came across a couple stretched out on wooden lounge chairs, Hannah explained that the chairs were made from wooden train sidings and still stood on the old wheels of coaches. Friends of High Line, the non-profit conservancy, works with New York’s Department of Parks and Recreation to keep it up and running.

It has not all been acclaim and adoration for the High Line, though. Rumbles about how it is intrusive and disruptive to the community—traffic snarls, rising real estate prices, and the real chance of strangers peeping into adjoining homes—have been getting louder. Not to speak of the gentrification of the neighbourhood itself, with the Chelsea and Meatpacking districts now among the hippest and most expensive in Manhattan. David and Hammond have rued that the park was “a victim of its own success” and set up a High Line Network to share their learnings with other urban park projects across the US, including Houston’s Buffalo Bayou Park, Philadelphia’s Rail Park and Miami’s Underline.

The High Line is not the first of its kind across the world—in North America, Europe and East Asia—linear and elevated parks have been popular. The Promenade Plantée in Paris is one of the world’s oldest, built in 1993 over an abandoned 19th century railway viaduct. The original Seoullo 7017 in Seoul was built in 1970, with a newer version opened in 2017 that includes plenty of activities for children. The Klyde Warren Park in Dallas, Texas, runs over a freeway and has enough room in its 5 acres for exercise classes and food trucks. In contrast to this, the Bentway in Toronto is under the Gardiner Expressway, and offers an ice-skating trail, with plans to dedicate an open space for art exhibitions, music performances and farmers markets.

And then there are the vertical gardens created around residential spaces (not for public use), such as the Bosco Verticale towers in Milan. Meant to be a prototype for sustainable housing, the vertical garden that wraps itself around each of the two towers contains trees, plants and shrubs that amount to nearly 20,000 sq mt of forest land. In Sydney, One Central Park is a similar design concept, with living green walls of homes and the entire façades covered with trees and plants.

In India, however, urban gardens have to fight for more practical or profitable use of scarce land. For instance, Mumbai’s derelict textile mills could be converted into public green spaces, as was indicated in initial plans drafted by Charles Correa. But that fell through almost immediately. However, Madhav Pai, India director of the WRI Ross Centre for Sustainable Cities in Mumbai, says urban conservation is picking up pace in India. “Especially once a place gets Unesco World Heritage status, conservation and restoration are almost a given,” he says, citing projects like Manek Chowk in Ahmedabad, Fontainhas in Goa and the Edwardian and Art Deco architecture of Mumbai. But this does not necessarily translate into what Sandhya Rao, a Bengaluru-based architect and co-founder of Urban City Labs, calls adaptive reuse—the process of giving a derelict space a new form or different function.

“There is no space in Mumbai that is completely abandoned,” says Pai, “because there are always squatters, children playing, or some such activity going on there.” If there is to be adaptive reuse, then city flyovers would be his first choice, since “so many have been built without any thought for function or design.”

Rao, though, refers to the Kochi Biennale as a “phenomenal example” of how a historic town centre gets converted into a space for public art and culture. “The physical intervention to any of the structures is minimal, but the space gets a new function, defined by a new narrative,” she says. Another such example she cites is Freedom Park in Bengaluru, a former prison repurposed into a park in 2008, where public gatherings and events (including organised protests) take place.

According to Rao, any reimagining of public spaces needs local residents and planners to be engaged in the process and consider the multiple needs of such spaces. “We cannot adopt the Western model directly in India because every space here has multiple roles. For instance, an open maidan can be used to play cricket in the evening and be converted into a puja pandal the next morning by the community.”

Pai has a similar reluctance to approaching the concept from a Western perspective, “Here, people are demanding more basic needs such as education and electricity. Space for walking and leisure is a distant need, so any conservation or restoration planning needs to be married to a practical use. And that vision is missing.” He gives the example of how Mumbai’s CST building got a facelift, but that project was not taken further to include walking spaces or leisure activities around the precinct. “Even in the BMC, there is a roads department for maintenance but there is just no institutional responsibility or authority for the kind of urban regeneration projects we are talking about.”

First Published: Sep 14, 2019, 08:45

Subscribe Now