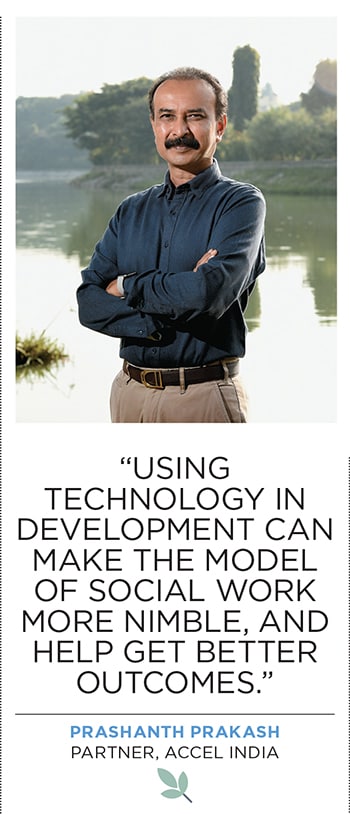

His volunteers and partners managed to reach the 70,000 mark in a week. “Soon, other funders asked us if we could do this for them too,” says Gayatri Nair Lobo, COO, ATE Chandra Foundation. So, along with contributions from donors, including Swati and Ajay Piramal, Hemendra Kothari, Noshir Soonawala, Lalita Gupte, Azmin and Noshir Kaka and others, the ATE Chandra Foundation reached over 10 lakh people in Mumbai and provided close to 2 crore meals in two months, starting April. Out of this, the Foundation, on its own, directly impacted around 2.2 lakh people with 73 lakh meals. Each kit consisted of rice, wheat flour, vegetables, fruits, oil, sugar, salt, pulses and spices that would suffice a family for at least two weeks, along with hygiene products like soaps, sanitisers and masks, says Lobo. A total of Rs 11.47 crore funds were leveraged with the help of co-donors. ![virtuous capital3 virtuous capital3]()

Lalita & Noshir: Getty Images

As his volunteers packed these meals in the NSCI Dome in Mumbai’s Worli (before it was converted into a Covid hospital), Chandra and his wife Archana would visit, spending time with the team and other NGO leaders to guide and motivate them. “Because philanthropy is to lead by example and care for people from your heart,” Chandra says.

The banker-turned-private equity (PE) investor led many other diverse Covid-related health programmes, working with multiple stakeholders. This inacluded building a 219-bed ICU facility operated by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation at NESCO, Goregaon donating close to one lakh personal protective equipment (PPE) kits, 29,350 N95 masks, eight ventilators and five oxygenator machines across Maharashtra and Rajasthan partnering with Harsh Mariwala’s Marico Innovation Foundation to support five scalable solutions around ventilators and PPE kits helping in execution and data analysis of the sero-survey conducted among 15,000-odd people in Mumbai to understand the extent of the infection among the population and organising hygiene awareness campaigns in slum areas of the city.

He directly contributed close to Rs 5 crore for these health initiatives, and leveraged approximately Rs 8 crore from his network. Apart from Covid relief and rehabilitation efforts, his foundation continues its regular programmes of rural development, capacity and leadership-building, and encouraging everyday philanthropic giving among common people.

Chandra, along with his wife Archana [CEO, Jai Vakeel Foundation], donated Rs 27 crore of personal wealth in FY20, according to the EdelGive Hurun India Philanthropy List released in November, earning him the distinction of being the first and only professional to be included in the list that is otherwise populated by entrepreneurs.

India has had a good, and growing, legacy of charitable businesspersons setting aside a certain proportion of their billion-dollar net worth to solve social problems. But Chandra represents an emerging cohort of professionals—venture capitalists (VC), PE investors, bankers, consultants and others—who are taking it upon themselves to not only share money, but also time, expertise and network to benefit the development sector. Technology, transparency and evolving attitudes towards wealth are reshaping approaches to giving, with professionals becoming more results-focussed.

The efforts and contributions made by this group are fragmented, and not much public data is available for consolidation, comparison or analysis yet, as it is in the case of top donors. But experts in philanthropy and strategic giving believe professionals are active now more than ever, with the emergencies imposed by the pandemic increasing their intent and the quantum of financial donations.

![virtuous capital5 virtuous capital5]()

Stronger Together

“We have the Tatas, Premjis and other prominent legacy donors at the top of the philanthropy pyramid. The bottom has retail, everyday givers. It is the middle of the pyramid, comprising professionals and executives, which has been growing from strength-to-strength, becoming more organised and structured,” says Srikrishna Murthy, co-founder of Sattva Consulting, a social enterprise that works in the non-profit space. He says one of the main reasons for this is the structuring and the formalisation of the social sector over the years.

Vidya Shah, CEO of EdelGive Foundation—it brings out the philanthropy list mentioned earlier—says that in her experience, personal income that professionals are willing to invest in philanthropy ranges from Rs 5 lakh to Rs 50 lakh per year. “Their long-term engagement with organisations has resulted in increased quantum over the years,” she says.

The professionals they work with are in the 40 to 50 age group, and from backgrounds including IT, manufacturing, financial services and others. The main difference between them and billionaire givers, according to Shah, is that the former have “openness in accepting innovation in giving and adopting flexibility in funding”.

Professionals are more welcoming, she explains, to fund non-traditional sectors and other areas such as organisational development. “For billionaire entrepreneurs, the landscape of their investments, owing to the size of their contributions, is much larger both in terms of project size and impact. They also prefer self-implementation of programmes, rather than engaging with implementing partners.”

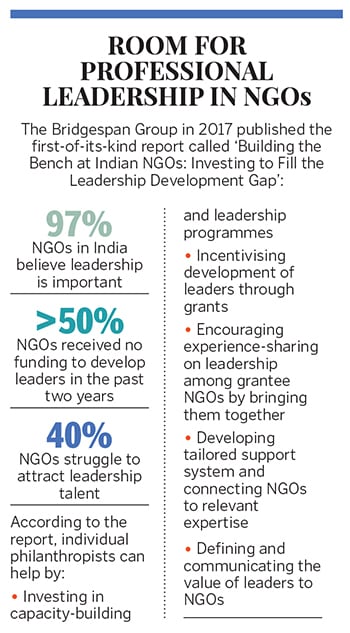

The ACT Grants, a Rs 100 crore Covid-19 relief fund formed by a group of VCs, PE investors and startup executives, is an example of professional philanthropic efforts centred around new-age technological innovations.

Some of the senior professionals who came forward to steer the initiative with their personal money and expertise include Prashanth Prakash, founding partner of Accel India, Mohit Bhatnagar, managing director of Sequoia Capital, and Vani Kola, founder of Kalaari Capital. Few of the country’s top startup entrepreneurs—like Curefit founder Mukesh Bansal, Cred founder Kunal Shah, Freshworks’ Girish Mathrubootham, Rebel Foods co-founder Jaydeep Barman—also came on board to give their time and resources to identify ventures that could be backed.

The financial support to fledgling startups working on products and services to combat the pandemic was in the form of grants ranging from Rs 20 lakh to Rs 1 crore. The investors did not pick up a stake in the selected ventures. A few small grants were made to portfolio companies for retooling their existing offerings to cater to urgent health care requirements of the pandemic. For example, with a grant of Rs 30 lakh, home health care provider Portea Medical came up with a tech-enabled remote patient health and monitoring system in coordination with state governments.

“Many people in the VC ecosystem were doing philanthropic work individually, so we thought that if we could pool in all our resources and expertise under one umbrella, it will help us be much more impactful,” says Prakash of Accel India. The focus of the grants was on sustenance and saving lives, he explains, adding that adapting to new challenges helped them fund scalable solutions that tackled changing situations on the ground. “We could go to the market fast because we were leveraging technology,” he says, explaining that at one point about 70 to 100 volunteers from these VC firms were actively looking at various proposals pro-bono to carry out diligence and present it to the investment committee that met almost every day.

![virtuous capital4 virtuous capital4]()

The consortium provided grants of Rs 86 crore to 54 companies working in 24 states between April and September, and is looking to disburse the remaining Rs 14 crore by December. In 16 priority states, ACT members are working directly with individual state and district-level governments.

Some of the organisations that received support include StepOne, Swasth (telemedicine and home quarantine) InAccel, Nocca (oxygen therapy) CritiCU, Dozee, Cloudphysician (remote monitoring) MyLab, Molbio, Healthians, qure.ai, 1mg (testing and detection) Zetwerk, Clovia, Karkhana.io (PPE solutions) Max Ventilator, Ethereal Machines, HFNC Devices (hospital infrastructure) ePsyclinic, Dost Education (mental wellness) Haqdarshak (sustenance).

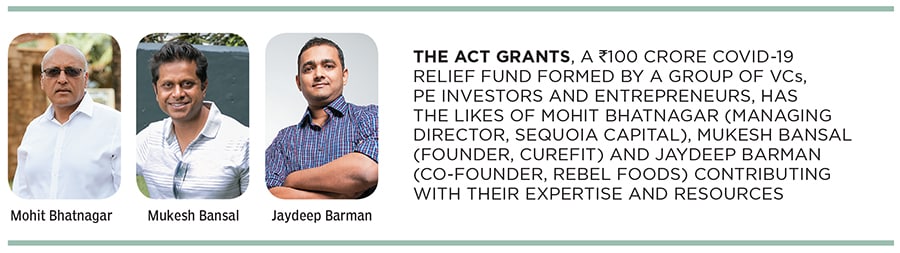

The approach ACT took reflected some of the key learnings from Prakash’s personal philanthropic journey, in which he has supported education and environment conservation causes by working with non-profits for over a decade. “My view has always been to see how technology can play a role in development, so we can make the model of social work more nimble, monitor it closely and get better outcomes,” he says. “We have to bring key aspects of business into philanthropy, like ROI [return on investment], deeper scrutiny of systems, and setting up metrics for results instead of being content with just making donations.”

Most senior professionals who are active philanthropists today have refined their donor behaviour over the years by being on the lookout for the best ways to support causes close to their heart, and learn new things along the way. For example, Kalpana Morparia, chairman, South and Southeast Asia, JPMorgan, who has been championing education of vulnerable children in rural areas in a personal capacity, first started with running a marathon to raise money for a charity. A Mumbai Mirror report from 2007 says that Morparia raised Rs 64 lakh out of the total collection of Rs 6.47 crore, the highest among individual runners.

![kalpana morparia_k5a0385 1 kalpana morparia_k5a0385 1]() Kalpana Morparia

Kalpana Morparia

Morparia describes the marathon as a wake-up call that pushed her to do something more. “It is relatively easy for the wealthy to give money because it is a way to assuage their guilt and feel good about themselves, but it is far more difficult to give your mindshare and your managerial capabilities to social causes. Those are far more valuable to creating a lasting impact,” she says.

Morparia’s mother, who died in 2007, had wanted her to take up the cause of supporting a school for underprivileged children. Her search for a non-profit that would help her work in that direction led her to Sunil Mittal’s Bharti Foundation.

In 2011, the banker visited one of the schools supported by the foundation in rural Haryana and realised that it was not just about educating children, but engaging with them to change behaviours and mindsets that would have a multiplier effect on the community. It was about building confidence, hygiene levels, and nutrition too—she recalls sitting down to have a mid-day meal with the children, only to realise how supply of good quality local food could be ensured by enabling parents to cook meals each day by rotation.

Morparia ended up personally adopting the school, and wrote a cheque of Rs 1.5 crore so that the authorities would not have to depend on anyone else for ongoing support and maintenance. Mittal [founder, Bharti Enterprises] subsequently invited her to be on his foundation’s governing board.

![virtuous capital6 virtuous capital6]()

She has since adopted five more rural schools: Three in Punjab (one of them in June this year), one in Rajasthan and one in Haryana. Her “real contribution” to these schools, according to her, comes from the learnings she draws from the foundation (which works with over 200 schools in the country) about how to develop best practices and work alongside teachers to implement quality support programmes.

Philanthropy is going to take up a “significant amount” of her time post retirement early next year, Morparia says. In her 12 years at JPMorgan, she has steered various causes in a professional capacity too, currently focusing on skilling, literacy and supporting small businesses. In 2019, the bank made a five-year philanthropic commitment of $25 million ($10 million in collaboration with the World Bank) toward these causes.

Inspirational personal stories of professional leaders is what prompted the launch of LivingMyPromise in 2018, a pledge that invites professionals worth more than Rs 1 crore to donate 50 percent or more of their wealth towards philanthropy. Co-founder Girish Batra says he wanted to do something for professionals to contribute along the lines of The Giving Pledge. Initiated by Bill & Melinda Gates and Warren Buffet in 2010, The Giving Pledge got the wealthiest in the world to commit at least half their net worth to philanthropy either during their lifetime or in their will.

“The idea that your parents and your pin code decide the kind of life you lead is what brought us like-minded people together to try and plug this imbalance,” Batra says. The group, which is all about fostering more collaboration among professionals to promote impactful giving, has more than 90 signatories, including Chandra, Luis Miranda, founder-director of the Indian School of Public Policy and founding team member of HDFC Bank, and Pramod Bhasin, chairman, Clix Capital.

Bhasin, along with Rare Enterprises founder Rakesh Jhunjhunwala, is one of the two Indians to be included in the Heroes of Philanthropy 2020 list brought out by Forbes Asia in November. “In a country like India, with its stark disparities, it is incongruous if wealthy people don’t give back,” Bhasin tells Forbes Asia. In the past year, the 68-year-old donated $2 million (Rs 13.3 crore) toward tech-led education and health care, and is estimated to have earmarked upwards of a total of $25 million (Rs 166 crore) for charity.

Shifting Perspectives

Economic progress and faster wealth-creation underlines modern philanthropic efforts, believes Atul Satija, CEO of GiveIndia and The/Nudge Foundation. He says the bandwidth and freedom that professionals have to participate in the development sector today, sometimes even by leaving their corporate careers behind, is because many of them have been able to earn money at an early age. “Historically, philanthropists were all building long-term institutions or doing direct charity in areas where there was structural failure of state and markets,” he explains. “As societies have become more complex, bigger and wealthier, philanthropy has turned to problem-solving by getting deep into a specific development issue for many years.” The latter, Satija explains, is a layered approach that is being practiced more by younger philanthropists.

Aditi Kothari Desai—fifth-generation professional from the Kothari family that owns the firm DS Purbhoodas & Co, and daughter of Hemendra Kothari, who founded DSP Financial Consultants in 1975—concurs with Satija’s observations. She explains how her forefathers contributed to building infrastructure and institutions like hospitals, public drinking water fountains, sanatoriums, schools and hostels. “Today’s giving is not about starting your own school or college or hospital, but strengthening existing institutions. It is about identifying strong social entrepreneurs and backing them in the problems they are trying to solve,” she says.

![aditi_010 1 aditi_010 1]() Aditi Desai

Aditi Desai

Desai, who is head of sales at DSP Investment Managers, is on the board of the Hemendra Kothari Foundation and the Wildlife Conservation Trust founded by her father. As part of her personal philanthropy, she is on the board of Dasra, an organisation for strategic philanthropy, and works with non-profits Muktangan (education), the Resource Centre for Interventions on Violence Against Women at the Tata Institute of Social Science, and the Association for Advocacy and Legal Initiatives in Lucknow that does pro-bono legal work for women’s rights.

Desai helps these non-profits with fundraising, campaigns and outreach. “I can’t just give money and forget, but it’s not for everyone to be that way. So I feel there should be no obligations in philanthropy. If I believe in certain causes and go deep to try and address them, that is a personal choice. There’s no competition, only inspiration,” she says.

Mekin Maheshwari is another young professional who represents this generational shift in the nature of philanthropic giving. After building software platforms at Yahoo and Ugenie, he had a lucrative career at ecommerce startup Flipkart where he rose to become the chief people officer, only to quit after six years and dive into the non-profit space.

It was simply the awareness of social issues that prompted him to do something. “For 35 years of my life, I didn’t even know the development sector existed,” he admits. “And that’s probably true of a lot of people in the country.” Maheshwari’s Udhyam Learning Foundation, launched in 2017, equips small grassroots businesses with training and technology. As per the website, it is inching closer to the goal of creating substantial, sustainable income for about 50,000 small businesses by 2021. Udhyam also introduces entrepreneurship curricula in schools and has reached about a million children.

![mekin maheshwari_5171 1 mekin maheshwari_5171 1]() Mekin Maheshwari

Mekin Maheshwari

Education and small businesses were among the most-affected sectors in the wake of the pandemic, prompting Maheshwari to take charge of creating a WhatsApp group in April. Five like-minded people came together to figure out how they can contribute towards navigating the crisis.

The group, called ‘Startups for Covid-19’, soon migrated to Telegram as hundreds of professionals expressed interest in contributing. Eventually, their discussions not only led to drafting policy interventions to help the government manage the crisis, but also mooted the idea of the ACT Grants.

Maheshwari realises that it is time to forge more collaborations and think out-of-the-box. The development sector is extremely small compared to the country’s humanitarian needs, he says. “Some of the largest organisations are still mostly providing service delivery, which is augmenting or adding to what the government is doing. Building capacity is great, but for change to happen faster, we need more talent, more money and a lot more people thinking about different ways to solve challenges around health, education and other needs.”

On the other end, it is important that non-profits also do not approach professionals only for their money or their network, but also for their skills and leadership qualities, believes Gita Nayyar, senior advisor at Fulcrum Ventures. She says many NGOs are led by well-intentioned people with a background in social work, but very little experience on knowing which company is likely to support which cause, how to prepare targeted proposals, campaigns and strategies.

“When the pandemic hit, CSR [corporate social responsibility] and professional donor behaviour realigned to Covid-19-related causes. The NGOs that are professionally aligned would be able to recover more quickly than those that are not, simply because professionals would help them understand the market and prepare fundraising and outreach accordingly,” says Nayyar, who is on the advisory committee of HelpAge India and a signatory with LivingMyPromise.

While the pandemic is diverting funds from non-Covid sectors, another challenge for NGOs is the recent Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment (FCRA) Act, 2020 that restricts foreign donations to the social sector. This makes domestic philanthropic funding all the more critical now, says Deval Sanghavi, co-founder of Dasra. “We may have set our commitment to Sustainable Development Goals [SDGs] back by five to 10 years now,” he says. “More funds by domestic philanthropists is always better, because it has less regulatory restrictions, and individual donors are also able to provide access to their own networks. So impact will not only be accelerated, but also sustainable.”

Luis Miranda, who is on the board of various non-profits apart from being chairman of the Centre for Civil Society, agrees. Calling the FCRA “badly timed”, he says even though NGOs may have a few bad players, just like there are in business, government or bureaucracy, the whole sector must not be seen as suspect.

![virtuous capital2 virtuous capital2]()

“There needs to be more constructive dialogues and trust between the government, non-profits and philanthropists so that we can solve problems and there is ease of doing charity,” says Miranda, who is also a senior advisor at Morgan Stanley and chairman of ManipalCigna Health Insurance.

Chandra points out that the social sector, which provides employment to millions of people and is a big partner to the government, is likely to see “at least a Rs 10,000 crore dip in funding. Now, the government and philanthropists have to think about how to fill this gap.” As a high-level member of the government’s CSR committee, Chandra says they have made recommendations, including setting up a social stock exchange, tax incentives and smoothening regulatory obstacles.

Going forward, according to Sanghavi of Dasra, it is important that professional philanthropists have the humility to understand the social sector, and know that the “perfect solution” they are looking for doesn’t exist.

“Development is difficult, it’s messy, and not a straight pathway between A and B. Professional givers need to realise that NGOs are actually creating markets. They are changing the way generations have thought about health care, women’s rights, education, and employment, which takes time and needs a long investment horizon,” he says. “But they often do not give the luxury of patient capital when it comes to NGOs as they do in the for-profit space.”

It is important for professional donors to have patience to listen and understand, believes Miranda. “The non-profit sector is different from the for-profit space. To come in here as a know-all will lead to not only you giving bad advice, but also putting off people on the other side. Let’s hear what non-profits have to say first.”

Murthy of Sattva believes that the middle-of-the-pyramid givers are quite young, unlike institutions who have passed the learning curve. “It’ll take at least three to five years for professionals to emerge as more strategic players in the ecosystem, and it’s going to be sporadic as long as they give only their money, and not their time, to the social sector.”

It’s all about starting small, but just starting somewhere, adds Chandra. “Getting into

philanthropy is like investing in the stock market. When you buy a share, you suddenly feel like you have equity. You feel good when it goes up and bad when it goes down. You learn from your mistakes, and that’s how you become a better investor.”

Image: Mexy Xavier

Image: Mexy Xavier

Kalpana Morparia

Kalpana Morparia

Aditi Desai

Aditi Desai Mekin Maheshwari

Mekin Maheshwari