Covid-19: Crowdfunding to the rescue

The culture of giving is picking up in India as crowdfunding platforms flourish and commoners turn philanthropists to help those in need

Image: Chaitanya Surpur

Image: Chaitanya Surpur

August 2020 was an exceptional month for Mumbai-based engineer Mihir Kamat and his wife Priyanka. It began with elation when they became parents to a baby girl, Teera. She was born normal and weighed a healthy 3 kg.

“Three weeks after she was born, her breathing would get heavy while feeding,” says Kamat. “Initially, the doctors thought it was normal and prescribed bottle feeding.” Two weeks later, when she was taken to the hospital, the doctors again proclaimed her healthy.

It struck Kamat during her vaccinations that all wasn’t well with Teera. Unlike normal babies who would cry in pain when given injections, his daughter didn’t seem distressed. “She kept smiling,” says Kamat. “And she wouldn’t push away or show any reflexes.” That’s when they decided, upon their doctor’s suggestion, to take her to a neurologist. And their worst fear came true.

The Kamats’s two-month-old baby was diagnosed with Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) Type 1, a genetic disease affecting the central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, and voluntary muscle movement. The disorder attacks the baby’s nerves and muscles, and as it progresses, makes it difficult for them to carry out basic activities like sitting, swallowing milk, and even breathe. SMA affects one in 10,000 babies and is the biggest genetic cause of infant deaths worldwide.

Thankfully, by the time the disease was confirmed, Mihir had already read up about the potential cure. But it would come at a staggering ₹16 crore. Zolgensma, a one-time gene replacement therapy that targets the genetic root cause of SMA and replaces the function of the missing or non-working survival motor neuron with a new one, needed to be imported to India. Globally, only some 500 children have been treated with Zolgensma so far. “We knew we had to move quickly since this is a fast degenerating disease,” says Kamat. “If I have to raise ₹16 crore, it will take me 16 lifetimes. That’s when we decided to look at crowdfunding.”

Crowdfunding, essentially, is the use of small funds from a large number of individuals to meet any financial requirements ranging from medical emergencies to higher studies. In early November, the Kamats raised a funding request on ImpactGuru, one of the many crowdfunding platforms in the country. In five days since the movement started, the family managed to raise ₹72 lakh from some 1,600 donors. It’s only about 5 percent of the target, and Mihir knows he has a long way to go, but through crowdfunding he’s taking baby steps towards a goal that, otherwise, would seem impossible.

“Every minute, almost 100 persons are admitted to hospitals and 30-odd health insurance claims are filed,” says Piyush Jain, co-founder and CEO of ImpactGuru. “What usually happens is that these treatments end up draining people’s resources severely and put them at the risk of debt. Crowdfunding provides a platform that doesn’t come with any payback liabilities while serving the purpose.”

Crowdfunding to the rescue

Today, crowdfunding in India is spread across numerous areas ranging from health care, education, and arts and culture, to animal welfare and entrepreneurship. Earlier this year, Kamal Singh, a 20-year-old son of an electric rickshaw driver from New Delhi, managed to raise ₹15 lakh for his tuition fees at the English National Ballet School in London on crowdfunding platform Ketto. Kamal was the first Indian to be selected to the illustrious institution.

“My father did not have the means,” Kamal tells Forbes India from London, where he is studying now. “My entire requirement was around ₹25 lakh. Within two weeks, we raised ₹15 lakh. And, so far, we have raised ₹18 lakh.” That was good enough to send him to London. “Of course, living expenses are very high here, and I am still dependent on the funds,” adds Kamal.

Much of the recent uptick in crowdfunding has also come about thanks to India’s massive mobile phone and internet penetration in the past few years, which, in turn, has also boosted social media activity. India currently has about 504 million active internet users, of which about 70 percent are daily users, according to the Internet and Mobile Association of India. The country’s smartphone base is expected to swell to 820 million by 2022, according to consultancy firm KPMG.

“Today, we are seeing a seismic shift in first-time givers,” says Anoj Viswanathan, co-founder and president of Milaap. “The internet has been changing how we interact and more so in our everyday behaviour. Giving is an inherent behaviour in our lives. Some are conscious about it, some aren’t.”

“Today, we are seeing a seismic shift in first-time givers,” says Anoj Viswanathan, co-founder and president of Milaap. “The internet has been changing how we interact and more so in our everyday behaviour. Giving is an inherent behaviour in our lives. Some are conscious about it, some aren’t.”

Viswanathan, along with Mayukh Choudhury, started Milaap in 2010 and has so far raised around ₹1,100 crore on its platform for 300,000-odd initiatives. “Ninety-five percent of this money has come from individual donors,” says Viswanathan. “The remaining have come from high net worth individuals or corporates.” Today, the platform has over 35 lakh users with 50 lakh donations. In fact, at the peak of the lockdown, a single user paid close to ₹40 lakh towards migrant welfare. “With UPI, anybody can transfer amounts as low as ₹1. And we are seeing a surge as a result of the easier payment options,” Viswanathan adds.

Jain of ImpactGuru agrees. “The launch of UPI as a platform has led to an exponential growth in donations,” he says. It has also helped that Facebook-owned WhatsApp has rolled out its payment service for users in India after receiving approval from the regulators. “In China, once WeChat rolled out payments, it was the number one trigger for donations,” adds Jain. “New technologies have been democratising philanthropy and disrupting it for good.”

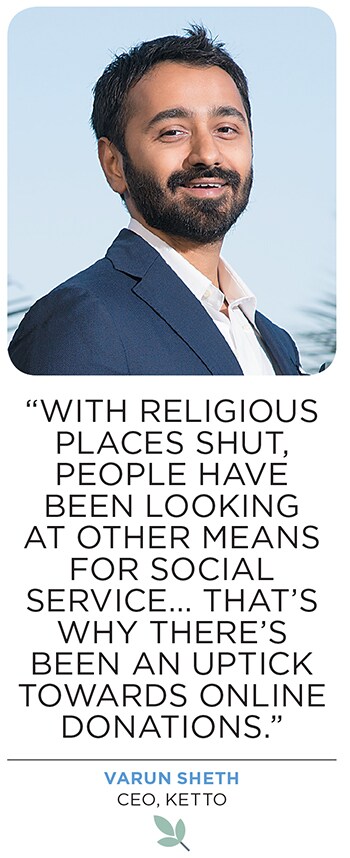

Now, with the Covid-19 pandemic sweeping across the world, there has also been a marked change in people’s approach towards philanthropy. “Pre-Covid, much of the donations would come from Tier I cities, which has changed since,” says Varun Sheth, CEO of Ketto. “Almost 70 percent of our donors fall within the age group of 20 and 35. Also, with religious places and sites shut, people have been looking at other means for social service. That’s why there has been a significant uptick towards online donations.”

Milaap, Viswanathan says, saw some 12,000 unique causes being raised on its platform as a result of the pandemic. Among them was an initiative to provide support to 300 clay artisans in West Bengal. The initiative has raised ₹1.5 lakh so far. On Ketto, at the peak of Covid-19, circus company Rambo Circus managed to ₹12.5 lakh towards supporting 90 artistes, who had been rendered jobless as a result of the nationwide lockdown.

“Giving has increased,” says Atul Satija, founder at The/Nudge Foundation, and CEO at GiveIndia. “There is widespread adoption of technology and we now have one of the cheapest data in the world. Unlike travel, charity is a discretionary spend, and with the UPI revolution, it provides an opportunity to give easily. People are looking at rational causes and, as an industry, we will see sharper targeting as donors’ expectations keep going up.”

Kamal Singh raised ₹15 lakh on Ketto for his tuition fees at the English National Ballet School in London. Image: Arnaud Stephenson

It also helps that such causes often find endorsement from celebrities helping spread the word. For instance, in October, the family of Faraaz Khan, the son of Bollywood actor Yusuf Khan, managed to raise about ₹15 lakh for his treatment after filmmaker Pooja Bhatt sought crowdfunding for it.

Not an easy task

Yet, despite seemingly easy ways of raising funds, companies have also had to ensure adequate protection from possible frauds.

Setting up a fundraiser is often easy on the platforms, and almost all of the current platforms provide that for free. That means once a request for a fundraiser is raised, platforms will do the necessary background checks and weed out those they feel aren’t genuine. These could be through manual verifications, checking with hospitals, seeking bills and other documents etc. “This is essentially the do-it-yourself (DIY) model,” says Sheth of Ketto.

The first round of funding usually has to come from friends and close relatives to ensure authenticity and credibility before others can begin to start donating for the cause. In the meantime, companies pay close attention to the kind of transactions and the location from where the funds are being donated. “We use all sorts of tools to monitor the authenticity of the causes,” says Viswanathan. “There are serious signals through data sciences that help us track suspicious activity.”

The first round of funding usually has to come from friends and close relatives to ensure authenticity and credibility before others can begin to start donating for the cause. In the meantime, companies pay close attention to the kind of transactions and the location from where the funds are being donated. “We use all sorts of tools to monitor the authenticity of the causes,” says Viswanathan. “There are serious signals through data sciences that help us track suspicious activity.”

Under the free model, donors have the chance of tipping the platform for their services. Then, there is a premium model where the platforms charge a commission, usually around five percent of the funds raised, where it will help organise multiple fundraisers and actively promote social media campaigns in addition to content curation. That includes a dedicated relationship manager, who will help with building the narrative.

“Until August 2020, we used to charge a commission for the projects,” Viswanathan says. “Since then, we have decided to make it free with the options for donors to tip us. Making it free has helped us reach out to more people and segments. There has also been a spike in the tip.” In many cases, particularly in the case of health projects, funds are directly transferred to the hospitals. It has also helped that health care companies have begun to invest in crowdfunding platforms. In 2018, ImpactGuru raised funds from the Apollo Hospitals Group, among others.

“We have direct partnerships with over 1,000 hospitals,” says

Jain of ImpactGuru, “which helps us in validating the information.” In many cases, funds raised on the platform are stored in the company’s bank account before they are disbursed to the end-user. “That way we can control the flow of money,” adds Jain. “From manual verification to disbursing, we can then ensure that no fraudulent activities take place. It’s a four-stage due diligence process.”

In case a patient passes away or the funds raised for a cause exceeds what is needed, the platforms inform the donors and either provide a pro-rata return on their donations or seek to use that fund for a similar project. “For the donor, since they have already paid the amount, they mostly ask us to use it for another project,” says Jain of ImpactGuru. “But our job is to be transparent to the donor.”

There is also an attempt at solving problems towards specific causes. For instance, Mumbai-based Wishberry focuses only on creative projects, including films, music, publishing, comics, theatre, and more. Although ImpactGuru helps raise funds for numerous projects, it has been steadily turning its focus on health care.

“Unlike in the US and Europe, there isn’t much help for creative artists,” says Anshulika Dubey, co-founder of Wishberry. So far, Wishberry has raised about ₹ 17 crore towards 600 projects, of which a significant amount has come from the artist community. The company charges a nine percent commission, and in return helps with the pitch note and the kind of rewards they can offer to the donors, among other services. “It doesn’t make sense for us to pitch for a creative project alongside a project to raise funds for a life-threatening disease. That’s why we took a conscious decision to focus on one area.”

The sudden interest around crowdfunding has also brought some serious investor money into the companies. ImpactGuru has raised $2.5 million in equity funding so far from Apollo Hospitals Group, RB Investments, Currae Healthtech Fund, Venture Catalysts, and other investors. Wishberry has raised about ₹10 crore from investors, including former Google India head Rajan Anandan, Sharad Sharma and Series A by Reliance and UFO.

The sudden interest around crowdfunding has also brought some serious investor money into the companies. ImpactGuru has raised $2.5 million in equity funding so far from Apollo Hospitals Group, RB Investments, Currae Healthtech Fund, Venture Catalysts, and other investors. Wishberry has raised about ₹10 crore from investors, including former Google India head Rajan Anandan, Sharad Sharma and Series A by Reliance and UFO.

Ketto, on the other hand, has raised a total of $800,000 from venture capital funds, including Indusage Partners, India Internet Fund, Mumbai Angels, Chennai Angels, and LetsVenture. Milaap has raised some $1.9 million from the National Research Foundation of Singapore, Toivo Annus, the late founder of Skype, Lion Rock Capital, Jungle Ventures, and others. Together, almost all the platforms have raised in excess of ₹1,000 crore for numerous causes since they were founded.

Yet, India still has a long way to go when it comes to charity. According to the World Giving Index, it ranked 82nd among 128 countries for its generosity over the last 10 years. Data showed that only about 34 percent of people had helped a stranger, 24 percent donated money and 19 percent volunteered for some cause. Much of that was largely due to India’s strong culture of unorganised donations towards family, community and religion.

“These are early days for crowdfunding in India,” says Satija of GiveIndia. “The work isn’t over yet. It is only starting, but what gives us the confidence is that giving in India has certainly increased.”

First Published: Nov 26, 2020, 14:53

Subscribe Now