The frugal innovators at IIT-Bombay

Housed in a small shed at IIT-B, the Biomedical Engineering and Technology (incubation) Centre, or BETiC, is nurturing medtech innovators to create low cost, yet high quality medical devices

Video by: Varsha Meghani & Naini Thaker Music by: Sophonic Media

At MEDIC 2015, a five-day hackathon held at IIT-Bombay, two friends, both engineers, decided to find a solution for the 2.8 million people who die of heart or lung diseases in India every year.

The ubiquitous stethoscope, they learnt, was riddled with drawbacks—even sophisticated versions provided only faint sounds of the heart and lungs, making diagnosis arduous. Teamed with a doctor, who knew the problem first hand and was also present at the hackathon, the trio began brainstorming on ways to create a better stethoscope—one that could be used even by primary health care personnel like the Accredited Social Health Activists (Asha) in rural India.

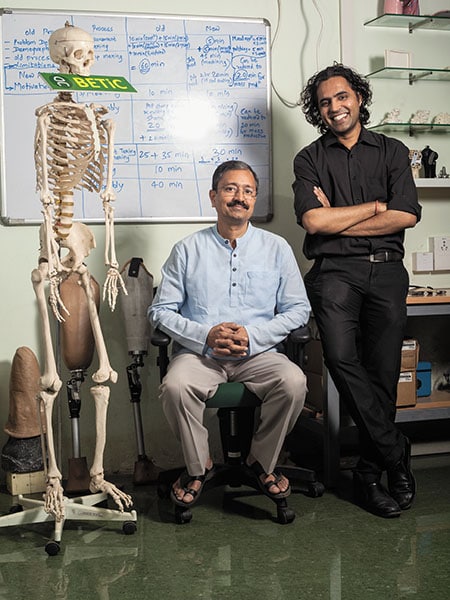

Professor B Ravi (left), the force behind BETiC, and Rupesh Ghyar, senior executive officer

Professor B Ravi (left), the force behind BETiC, and Rupesh Ghyar, senior executive officer

Image: Aditi Tailang

Five days of perseverance paid off as Adarsha K, Tapas Pandey and Dr Nambiraj Konar were able to create a ‘digital stethoscope’. Besides amplifying heartbeats and lung sounds, the prototype also converted them into an audio file, which could then be shared over Skype. “So, an Asha worker in a remote village can capture a patient’s stats and share them with a doctor located elsewhere,” explains Adarsha, while offering Forbes India a chance to check out the device.

Sure enough, the sounds are sharp and clear. The stethoscope he holds out is a refined version of the clunky prototype that has undergone many iterations since the hackathon, where the trio clinched the top prize.

They were later offered a fellowship at the Biomedical Engineering and Technology (incubation) Centre, or BETiC, at IIT-Bombay, where they could refine their prototype, undertake clinical trials and take it to market. “It was a no-brainer,” beams Adarsha, who quit his job at Larsen & Toubro in Mumbai and Pandey at a semi-conductor firm in Hyderabad to take up the offer. “We always wanted to work in the medical devices space.”

For comparison, Adarsha holds out the “BMW of stethoscopes”—the Rs 16,000 Littmann made by US-based 3M. The sounds were faint compared with the Rs 8,000 stethoscope of Ayu Devices, the startup that Adarsha, Pandey and Nambiraj formed in mid-2017 after almost two years of incubation at BETiC, which culminated in clinical trials and regulatory approvals for the device. They have received orders for 60-70 of their stethoscopes with another for 450 devices in the works.

In fact, if a doctor doesn’t want to do away with her regular stethoscope, she can simply attach Ayu’s digital module to her existing device. Pandey adds that they’ve also created a version where audio data can be shared via Bluetooth. Coming up will also be a ‘smart’ version that will leverage Artificial Intelligence to read patients’ data, doing away with the need for doctors in the initial stage. As Adarsha points out, this is useful in a country like India where the doctor-to-patient ratio is a dismal 1:1,700.

Ayu Devices is emblematic of the work progressing at BETiC. Housed in a shed-like structure on the IIT-Bombay campus in Powai, one would not think that the centre—a collaboration between IIT-Bombay, the College of Engineering, Pune and Visvesvaraya National Institute of Technology, Nagpur, set up three years ago—is a hotbed of innovation.

Yet, that is exactly what one stumbles upon.

The digital stethoscope is just one of 12 inventions—screening and monitoring devices to surgical instruments and patient-specific prosthesis—that have been taken to market by BETiC. All this from a pool of 100 prototyped devices 35 patents have also been filed along the way.

Professor B Ravi, the force behind BETiC, is quick to point out that the centre exists “not to write research papers or file patents, but to ensure that the devices actually reach the people they are made for”.

The Indian market for medical devices is estimated to be $5-6 billion (Rs 35,000 crore) and imported devices account for 80 percent of that and they are mostly used in private hospitals. “So poorer patients often go unserved,” says Ravi. Moreover, only about 300 of the 800-odd Indian medical device manufacturers are licenced, so quality is an issue, adds Rupesh Ghyar, senior executive officer at BETiC.

Given this “pull” for indigenous medical device innovation, the duo at BETiC along with experts from diverse fields are channelling India’s medical and engineering talent to create high-quality, low-cost medical devices. “Our work is not about ‘Make in India’ by multinationals, but is in fact ‘Made in India’ with our designs, skills and manufacturing capabilities,” says Ravi.

But creating the infrastructure for ‘Made in India’ devices has been challenging. Especially given the “big fat wall” that stands between academia and industry, explains Ravi. “The academia is happy to do research in labs and create prototypes while industry will invest in manufacturing and distribution only if the product is saleable,” he says. “But who will take the device from prototype to [saleable] product stage? There is a deep ‘valley of death’ between these two.” It is this critical gap—where pilot manufacturing, clinical trials and regulatory clearances are undertaken—that BETiC is trying to plug.

The centre has developed a multi-disciplinary, process-driven approach to do so. In a four-step approach, the teams must first ‘Define’ the problem they want to solve based on their interactions with health workers, then design and ‘Develop’ a prototype. Once a functional prototype is ready, the team must ‘Deliver’ by undertaking clinical trials and securing regulatory approvals, after which they must ‘Deploy’ the device in the market either by licensing it to local companies or setting up their own startups. “Instead of sitting on islands of expertise, we try to bring together medics, scientists, engineers, innovators and entrepreneurs. That’s how innovation happens,” says Ravi.

Throughout this difficult, often lengthy, journey from idea to reality, BETiC provides complete infrastructure assistance at its fully-equipped lab.

Take the case of a prosthetic leg developed by BETiC in consultation with researchers from IIT-Guwahati, IIT-Madras, technicians of Mumbai-based NGO Ratna Nidhi Charitable Trust that provides free ‘Jaipur Legs’ to amputees across India, doctors from the MGM Centre for Human Movement Science, Navi Mumbai, and amputees themselves.

It all began when Rajiv Mehta who runs Ratna Nidhi approached BETiC in mid-2015. He was looking for a more efficient way to make a leg prosthesis as the traditional Jaipur Leg posed problems: It was a time-consuming process (6-8 hours per leg which means the trust could serve only two patients a day), and the plaster mould around a patient’s leg stump was not only painful but could take several hours to dry on a humid day. Moreover, the Jaipur Leg has a rigid knee joint which means patients end up walking awkwardly.

After much research and consultation with domain experts and users, the BETiC team proposed 3D scanning to take an amputee’s measurements and 3D printing to create the mould and socket. In late 2015, Ratna Nidhi was awarded the Google Impact Challenge for Disabilities award, including a grant of $350,000, to make 1,000 prosthetic legs using this new technology.

Several iterations of the prosthesis followed until a scalable product was developed in two years. “We are encouraged to fail early, fail quickly over here, and take feedback from industry and users,” says physiotherapist and BETiC fellow Dr Trimbak Kawdikar, who worked on the project.

Today, after a patient’s measurements are taken tailor-like, the stump and socket are recreated using computer-aided machining of polyurethane foam, as 3D printing proved to be slow. The solution is more precise, has better functionality, and can be completed in 2-3 hours. “This has given me more flexibility and a new lease of life,” says Aslam Sheikh, a bangle-maker, who was one of the first amputees to wear BETiC’s prosthetic limb.

While this patient-specific innovation was taken to market by Ratna Nidhi, other devices like a multi-degree, flexible laparoscope, designed to provide maneuverability when performing minimally invasive surgeries, have been licenced to local companies to take forward the manufacture and distribution. “We discourage our innovators from selling-out to multinationals because the price will shoot up. What’s the point of innovating locally, if the Indian population cannot benefit from it?” says Dr Ghyar.

And so it is. Thanks to the efforts of institutions like BETiC, Indian medical device companies are starting to breed. Padmaja Ruparel, president of the Indian Angel Network which has invested in a handful of medical device companies (not from BETiC), points out that the “Indian health care system, or the lack of it, is enabling young entrepreneurs to create disruptive/low-cost devices for the Indian market, as well as for other countries.”

The potential is huge with the medical devices industry in India growing at about 15 percent annually and set to reach at least $25-30 billion by 2025, according to Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu India.

But for the ecosystem to truly mature, involvement from all stakeholders is key—institutions that allow innovation to flourish, investors with a high appetite for risk and long gestation periods, as well as government support. Only then will quality health care be affordable and accessible to all.

First Published: Apr 30, 2018, 11:36

Subscribe Now