Sutirtha Bhattacharya: Powering Coal India

By streamlining the clearance process and investing in technology, Sutirtha Bhattacharya has engineered a turnaround at Coal India, while not losing sight of environmental issues

Image: Arindam Mukherjee for Forbes IndiaSpend time with Sutirtha Bhattacharya and it becomes apparent that the chairman and managing director of Coal India Ltd has a razor sharp focus on two Es—efficiency and ecology.

Image: Arindam Mukherjee for Forbes IndiaSpend time with Sutirtha Bhattacharya and it becomes apparent that the chairman and managing director of Coal India Ltd has a razor sharp focus on two Es—efficiency and ecology.

The 59-year-old chief of the world’s largest coal producer is passionate about driving this change. Produce more but, at the same time, minimise the environmental impact has been the guiding mantra for Coal India under his tenure that began on January 5, 2015.

The results are for everyone to see. Before Bhattacharya took the helm at the state-owned behemoth, crippling coal shortages had become headline news. Production had stagnated and power plants—the largest customers of Coal India—were running on dangerously low buffer stocks of coal. Though a lot had to do with inadequate transport facilities through railway lines, the end result was unhappy consumers and power blackouts during the peak of summer.

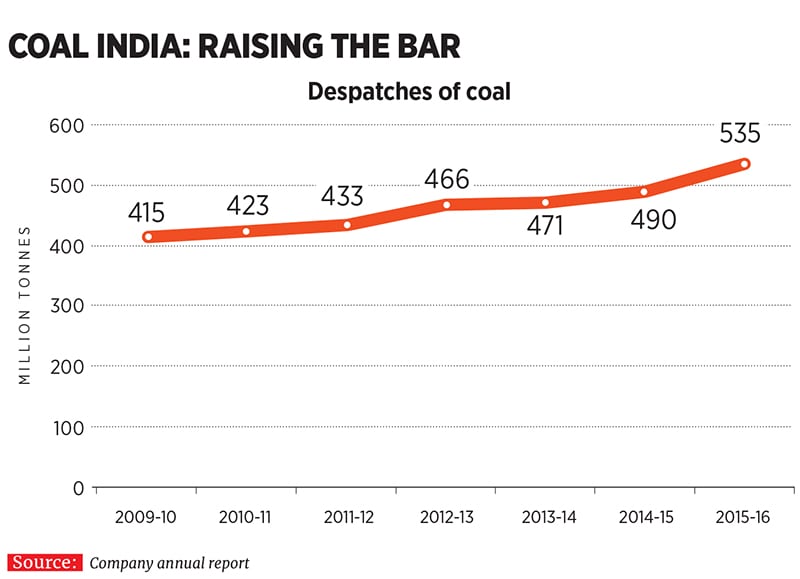

All that started to change after Bhattacharya, a 1985 batch (Telangana cadre) IAS officer, took charge of Coal India. His priority was to “ramp up coal production and supplies” to meet the country’s demand for coal, he had said when he took charge. A year-and-a-half later, coal production has increased to an all-time-high of 535 million tonnes for the year ended March 2016 from 433 million tonnes in 2011, an increase of 23 percent. The company earned Rs 14,274 crore in net profits (lower than the all-time-high of Rs 17,356 crore in 2013, but that is mostly due to a decline in the price of coal), which makes it the most profitable company among the recipients of the 2016 Forbes India Leadership Awards.

A year-and-a-half later, coal production has increased to an all-time-high of 535 million tonnes for the year ended March 2016 from 433 million tonnes in 2011, an increase of 23 percent. The company earned Rs 14,274 crore in net profits (lower than the all-time-high of Rs 17,356 crore in 2013, but that is mostly due to a decline in the price of coal), which makes it the most profitable company among the recipients of the 2016 Forbes India Leadership Awards.

As far as meeting the country’s coal demand is concerned, Bhattacharya has lived up to his word. Coal India ended the previous financial year with a surplus production of 58 million tonnes and an additional 39 million tonnes was with power utilities as buffer stock.

This reversal in fortunes has much to do with the changes Bhattacharya has implemented to clear the bottlenecks in production and mining. Take getting permissions for new mines, for instance. Coal India operates through eight subsidiaries that own and run mines in India’s coal belt of Jharkhand, West Bengal, Odisha and Chhattisgarh, apart from Maharashtra, and each state has its own set of rules and regulations governing mining of coal. Local laws have to be complied with. And most importantly, local communities have to be taken along when a new mine opens in an area.

This was a task that couldn’t be handled from Coal India’s headquarters in Rajarhat, Kolkata, or even the head offices of the local subsidiaries. Company officers had to be present at the local level to get permissions. Soon after Bhattacharya took over, he instituted a process to induct management trainees in environment and corporate social responsibility roles. They were tasked with getting permissions and within a matter of months, new mines started opening and production increased.

The quantum of production from individual mines, too, is monitored on a daily basis. If production falls short of target, reasons are sought from the local managers at the site.

These on-the-ground initiatives were backed by assistance from the central government’s ministry of coal. Industry watchers say it helped that the government appointed a single minister, Piyush Goyal, to handle coal, power, mines and new and renewable energy, which is a departure from previous practice. “The government and regulators have provided us all the support we needed,” says Bhattacharya. The help has come in two forms. First, the centre liaises with states to get bottlenecks eased. Chief secretaries and district collectors are put on video conference calls to ensure that clearances (mainly relating to the environment and land acquisition) for new mines are dealt with in a time-bound manner. “They know that if there is a delay, there will be questions from the top,” Bhattacharya says.

The help has come in two forms. First, the centre liaises with states to get bottlenecks eased. Chief secretaries and district collectors are put on video conference calls to ensure that clearances (mainly relating to the environment and land acquisition) for new mines are dealt with in a time-bound manner. “They know that if there is a delay, there will be questions from the top,” Bhattacharya says.

Second, help from the centre has come in the form of better facilities by the Indian Railways. India’s mines are in remote locations where transport links are either poor on non-existent. Transporting coal from the mine to customers was, and remains, a major challenge.

This is mostly taken care of by the railways and the new rail lines being laid in Odisha and Jharkhand are expected to considerably improve transport. To further expedite delivery, these new railway lines will be connected to the eastern dedicated freight corridor, which is under construction. Without this connection, “we will have a situation where the coal moves from a four-lane highway [the new railway lines] to a two-lane highway [the existing clogged rail network],” explains Bhattacharya.

It is also credit to Bhattacharya that he has taken cognisance of the impact technology can have on the venture. His vast and varied stints in Andhra Pradesh have given him the ideal launch pad to think about Coal India’s future and the role information and communication technology can play in enhancing productivity without harming the environment.

In his first job as district collector of Prakasam in coastal Andhra, Bhattacharya ordered the installation of wireless sets in the area. During a visit by former prime minister PV Narasimha Rao, a widow who had not received her pension complained. In those pre-cellphone days, he was able to check on the status of her pension within minutes by communicating via a wireless set with a local officer in her village.

Time has only increased his penchant for technology. At Coal India, Bhattacharya has led the charge to install software like Minex, which surveys mines and evolves a work pattern best suited to each mine. The programme utilises workmen more efficiently and helps them plan their routes in underground mines better.

This and several voluntary retirement schemes implemented over the years have led to a large reduction in manpower to 322,404 employees, compared with 346,638 in 2014, making Coal India a leaner and more efficient company.

While he was focusing on efficiency, Bhattacharya did not lose sight of the second E—ecology. Under his watch, Coal India has acquired the best global software and equipment to reduce the ecological impact of coal mining. For instance, a terrestrial laser scanner helps Coal India deal with the waste that lies over an area near the mine. Coal that is mined on the surface renders a lot of land unusable. This area is restored by planting trees and other vegetation. The scanner helps the company plan the mining and also gives it an advance picture of what the restored area will look like.

In addition to this, Bhattacharya has moved steadily in the direction of e-procurement. “We saved Rs 600 crore on explosives last year by procuring it through online bids,” he says. Bhattacharya now has one big unfinished agenda—implementing an enterprise resource planning system for the company. While he is happy with the manner in which software has improved operations and efficiency, the lack of one common software system that can handle the various tasks of the company—procurement, waste management, mine surveys, etc—is a major shortfall. He’s engaging the Management Development Institute in Gurugram, Haryana, to plan for it, but says it may not be implemented during his tenure.

Bhattacharya is acutely aware that power plants along the coast prefer imported coal as the landed cost is cheaper. Coal India is now trying to match the lower rates of imported coal. Despite the noise over coal-powered plants, he says it will remain the primary power source for India. What he is keen on is improving the efficiency of energy conversion—more power from less coal. Coal with higher calorific content will also enable this transition.

India’s shortage of coking coal (used in steel manufacturing) has not gone unnoticed by him and the company may make acquisitions overseas to address that deficit. Coal India’s only acquisition to date, a coal mine in Mozambique in 2009, has not worked out as planned. “Unlike oil which is found near the coast or in water, coal is found in remote regions. Getting it to India at a competitive cost remains a problem,” says Bhattacharya.

Through the course of our conversation, it is apparent that the transformation at Coal India has as much to do with government assistance and monitoring as it has to do with the man at the helm. It helps that he’d been power secretary of Andhra Pradesh as well as managing director of Singareni Collieries Company, jointly owned by the central and Telangana governments.

“The working of public sector undertakings has undergone a sea change in the last few years. It is more and more system driven with clear procedures laid down,” says Dharmesh Kant, head of retail research at financial services company Motilal Oswal.

As he leaves the company on a solid footing for the next decade of growth, Bhattacharya has shown how a government company with the right support and intervention can grow. He refuses to comment on the fact that chairmen have very short tenures, but it is clear that longer tenures would go a long way in cementing the gains made.

If one reads between the lines, it also becomes clear that the 1 billion tonne target was more a figure of speech something said to fire up the imagination of employees than a firm number. Incredibly, if the company gets there, it would produce more coal in a single year than all of the US. “We will do whatever it takes to make India import free,” is all Bhattacharya is willing to let on.

First Published: Nov 22, 2016, 07:29

Subscribe Now