Adar Poonawalla: Improving access to vaccines

CEO of the ₹4,837 crore by revenue Serum Institute of India, is looking to grow the low cost, high volume vaccine-maker to ₹10,000 crore by 2022

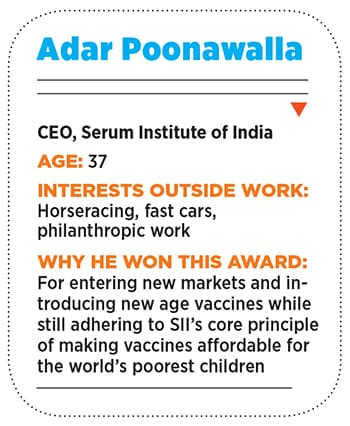

Adar Poonawalla, CEO, Serum Institute of India

Image: Vikas Khot

Forbes India Leadership Awards 2018: GenNext Entrepreneur

In 1996, a quarter of a million children were deafened, disabled and many of them killed by the meningitis-A virus that swept through Africa’s sub-Saharan belt. Every year thousands of children in the 25 countries stretching from Senegal in the west to Ethiopia in the east would get infected, but when the scourge hit its peak, national health ministers scrambled to find a solution. But at around $140 a dose, the vaccines retailed by Big Pharma were exorbitant.That’s when the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisation (GAVI) intervened. An international charity that promotes improved access to vaccines, GAVI partnered with the World Health Organization (WHO) and Seattle-based not-for-profit Path to design a vaccine for Africa—targeting the precise strain of disease while still being affordable. They roped in the Serum Institute of India (SII) to undertake the manufacturing and after four years of research, development and clinical trials in the mid-2000s, the vaccine—dubbed MenAfriVac and costing less than 50 cents a dose—was rolled out in 2010. Today, the meningitis-A virus has been all but wiped out of the vaccinated areas of the sub-Saharan belt.

“[SII’s] contribution to global health has been phenomenal,” noted Microsoft founder Bill Gates, during his visit to the vaccine-maker’s headquarters in Pune in 2012. (His foundation funds GAVI.) Founded by Cyrus Poonawalla in 1966, SII is the largest vaccine manufacturer in the world by number of doses produced. The privately-owned company claims to provide 1.3 billion shots every year to over 140 mostly low-and-middle-income countries.

“My father’s vision was always to provide low cost, yet high quality vaccines to the masses,” says Adar, chairman Cyrus’s 37-year-old son who took on the role of CEO in 2011. Settled into an ornate couch in one of SII’s baroque boardrooms, where awards, recognitions and pictures of visits by dignitaries, including Prince Charles and the late former President of India APJ Abdul Kalam line the walls, Adar, dressed in a sharp suit, talks of the time he joined the business. “Back then [2001, fresh off his undergraduate studies at England’s Westminster University] we supplied vaccines to about 30 countries,” he says. “I took it upon myself to increase our international presence. Today we’re in 140-plus countries.” Revenues too have grown at a CAGR of 32 percent since 2011 to ₹4,837 crore today. “We’re targeting ₹10,000 crore by 2022,” he slips in. *****Cyrus’s father, a horse breeder by profession, owned a stud farm in Pune. When the racehorses reached retirement age, they were donated to the government-owned Haffkine Institute in Mumbai, which made vaccines from horse serum.

As a 20-something, Cyrus, now 76, wondered why they couldn’t make those vaccines themselves a chance meeting with a veterinary doctor convinced him. He borrowed $12,000 in starting capital and set up a small laboratory in one corner of the stud farm—now contained within SII’s present-day 150-acre Pune campus—to extract the serum from horses and create vaccines. By 1967 the company rolled out its first tetanus antitoxin. Today, SII mass manufactures about 15 varieties of vaccines ranging from DTP (diphtheria, tetanus and polio) jabs to MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) shots.  The Serum Institute of India’s R&D facility in Pune. Adar Poonawalla claims many of their vaccines sell for less than the “price of chai” “The Poonawallas have had an underlying social motive to their work right from the beginning,” says Sanjiv Bhasin, executive vice president at the Mumbai-based financial services firm IIFL. “For them,” he continues, “it’s all about access. By mass manufacturing vaccines, they leverage economies of scale but also keep profit margins very low.”

The Serum Institute of India’s R&D facility in Pune. Adar Poonawalla claims many of their vaccines sell for less than the “price of chai” “The Poonawallas have had an underlying social motive to their work right from the beginning,” says Sanjiv Bhasin, executive vice president at the Mumbai-based financial services firm IIFL. “For them,” he continues, “it’s all about access. By mass manufacturing vaccines, they leverage economies of scale but also keep profit margins very low.”

In fact, Adar notes that many of SII’s vaccines sell for less than the “price of chai”. “By selling some of our vaccines at ₹5 [a dose] we often sell at a loss,” he rues. On average, margins are 20-30 percent, he says, which sometimes fall to 5 percent.

Because a majority of SII’s business is in the tender space—whether selling to the Indian government, or to international agencies such as Unicef, WHO and GAVI, who Adar counts as his big customers—price is the sole differentiator between winning and losing a contract. Moreover, tender prices go down by 20-30 percent every year. “It’s a great situation for the consumer, but as a manufacturer it’s not healthy because you spend five years developing a vaccine and in three to four years you see a huge price erosion,” says Adar.

“But the flip side,” he continues, “is that children will be vulnerable if we don’t provide the vaccines to immunise them.” He claims that every two out of three immunised children in the world are jabbed with SII’s vaccines. According to GAVI CEO Dr Seth Berkley, just like his father, Adar has shown “unwavering dedication” in improving access to vaccines around the world.

Philanthropic underpinnings aside, the reason SII has been successful thus far is because the company undertook early investments in infrastructure and capacity building. When demand spiked, they were able to meet it by drawing on these economies of scale. Says Adar, “At the time the move was risky, but we were able to foresee the demand. That’s why we have the largest capacities in the world today.” Sure enough, globally, SII is the largest vaccine manufacturer by volume, though value-wise it lags behind. GSK, Merck, Pfizer and Sanofi together make up 80 percent of the world’s vaccines sales by value. “We sell 1.3 billion doses of vaccines every year, but our turnover is just three-fourth of a billion dollars,” points out Adar, “Our average selling price is far less than a dollar.”*****undefinedSII claims to provide 1.3 billion shots every year to over 140 mostly low-and-middle-income countries[/bq]

The low price, high volume strategy might have worked for SII so far, but for how much longer? “Globally we have a 60 percent market share for the vaccines we produce. To grow from there in the existing vaccine space is difficult,” notes Adar. Quietly, he’s been plotting for the future by making fresh investments and new vaccines. A pneumococcal vaccine to take on pneumonia—a major killer of babies —will be launched next year. Earlier this year a rotavirus vaccine used to prevent death by diarrhoea in children was launched. In the pipeline is also a meningitis vaccine that will tackle five strains of the virus in one jab, and a cure for the dengue virus.

Adar also has his eye on European and American markets where margins are in the 200 to 300 percent range. SII acquired Dutch firm Bilthoven Biologicals, a leader in the manufacture of injectable polio vaccines (IPV), for &euro40 million in 2012 and spent another &euro72 million to scoop up defunct vaccine facility Nanotherapeutics in the Czech Republic in 2017. SII will spend another &euro30-40 million to get the facility up and running in the next two to three years, says Adar. Following a WHO recommendation for polio immunisation to be undertaken using inactivated, injectable polio vaccines, rather than the less safe oral varieties, there’s been a “huge shortage” of the former, explains Adar, adding that SII aims to become the largest IPV maker by 2020.

“The stronghold of SII is its efficient production technology… IPV might have been the main reason for the acquisition of Bilthoven but it is also a signal of the step-up to a higher market segment,” says Roeland van Dam, former CEO of the company who now serves in an advisory role. The step-up will of course come with its share of challenges, including pitting SII in competition with the makers (GSK, Pfizer, Merck, etc) of some of the world’s best-selling vaccines. But Adar remains unfazed. “We’re ready for the competition,” he says.

Neither is Adar discouraged by the current turmoil in the NBFC sector as he looks to diversify in the area. He’s set aside a corpus of ₹400-500 crore to provide loans to the salaried class. While the venture has only just taken off, Adar hopes to grow it “steadily and systematically”. Real estate is another area of growth, he contends, as he looks to develop his family’s large parcels of land in and around Pune into townships. A hotel built in partnership with the Ritz Carlton is slated for launch next year.

Clearly for Adar—who enjoys racehorses, fast cars and jet planes, but also makes the time for philanthropic work, notably, his ‘Adar Poonawalla Clean City Initiative’ that aims to make Pune more livable and sustainable—the galloping has only just started.

First Published: Nov 22, 2018, 17:35

Subscribe Now