How Takaya Awata became a QSR billionaire

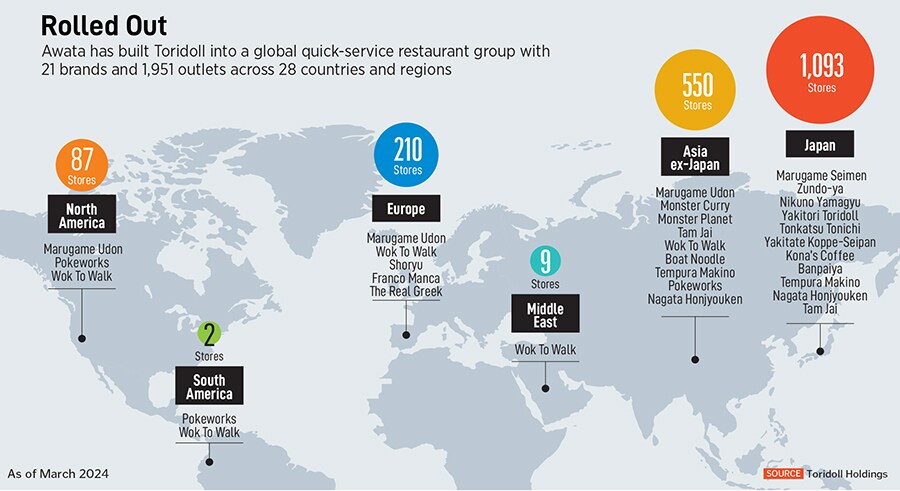

Awata started out with a modest ambition of owning three restaurants, yet today Tokyo-listed Toridoll Holdings has a network of nearly 2,000 quick-service restaurants across 28 countries and regions c

It was a promise to himself that stores number one and two were only a matter of time and he would soon achieve his modest goal of owning three restaurants.

Four decades later, Awata’s Tokyo-listed Toridoll Holdings has a network of nearly 2,000 quick-service restaurants across 28 countries and regions covering 21 brands. The flagship is Marugame Seimen, Japan’s largest udon noodle chain by both revenue and store count. The entrepreneur’s fast-food success has made him a billionaire and honed his ambitions.

“I would like Toridoll to compete on a global scale," says the 62-year-old president and CEO at his headquarters in Tokyo’s Shibuya district, adding that he’s aspiring to make it a ¥1 trillion ($7 billion) company by revenue in the next decade. To achieve those lofty targets, Awata wants to reduce Toridoll’s dependence on domestic diners in a shrinking home market and focus on overseas expansion.

The global quick-service restaurant industry grew at a compound annual growth rate of 5 percent between 2019 and 2023 to more than $1 trillion, the fastest-growing sector among the overall food-service market, Tommaso Nastasi, a Milan-based partner at consulting firm Deloitte, says by email. But in Japan, which is facing the challenges of a greying population, fewer full-time jobs and stagnant wages, restaurant operators must also grapple with rising costs and worker shortages.

Moreover, the country’s food business is intensely competitive, Awata notes. To grow domestically would mean snatching market share from rivals such as Hanamaru, the local udon chain owned by the more-than-century-old beef-bowl giant Yoshinoya Holdings, and Tokyo-listed Zensho Holdings, best-known for its affordable Sukiya beef-bowl chain, founded by fellow billionaire Kentaro Ogawa. Toridoll also has to contend with American juggernauts such as McDonald’s and KFC, which between them operate over 4,000 stores in Japan.

The competition for diners comes not only from other restaurants but also convenience stores’ bento box lunches and rice balls as well as supermarkets’ ready-to-eat meals, according to Tokyo-based Daiwa Securities analyst Shun Igarashi. “With the diversification in eating trends, companies are scrambling to get customers," he says.

A Marugame Seimen open kitchenImage: Courtesy of Toridoll

A Marugame Seimen open kitchenImage: Courtesy of Toridoll

Despite this, Toridoll, buoyed partly by an influx of tourists into Japan, posted record revenue of ¥232 billion in the latest fiscal ended March, with 38 percent generated from overseas. Net profit was up by 48 percent to ¥5.7 billion, helped by a weak yen that bolstered repatriated profits from overseas branches. But Toridoll’s shares, which had been trading at high earnings multiples after the pandemic as people resumed dining out, corrected 5 percent in the past 12 months. Awata, who became a billionaire last year and earned a place in the ranks of Japan’s 50 Richest, has a recent net worth of $1.1 billion.

By March 2028, Toridoll targets a more-than-threefold increase in net profit on ¥420 billion in sales—of which nearly half would come from outside Japan. This can be achieved, he explains, by more than doubling the total store count to 4,900, of which 3,000 should be overseas branches. (The company owns all but four of its nearly 1,100 domestic stores, while half of its 861 overseas shops are operated as franchises or joint ventures.) Awata says he expects overseas revenue to be higher, closer to 60 percent in the next three to five years.

Toridoll’s flagship brand, known as Marugame Udon outside Japan, already has 264 stores abroad, in locations as far-flung as Hawaii and Phnom Penh. Awata caters to local tastes, offering, for example, spicy broth in Indonesia and cold udon bowls with salad greens and fried chicken in the US. Apart from the udon chain, the company’s portfolio includes restaurants serving a range of cuisines, from Asian street food, ramen and yakitori to some Western fare, including pizzas and pancakes.

According to a report released in June by the Nikkei newspaper, 44 percent of Japan’s restaurant operators with outlets abroad are planning to add more, up from 28 percent in the previous survey published last year. Zensho, for example, plans to open 1,450 new shops by next March of which over 90 percent will be located overseas. Meanwhile, Osaka-based Food & Life Companies, best known for its conveyor-belt sushi chain Akindo Sushiro, with more than 1,100 eateries across Asia, entered the US in April.

According to a report released in June by the Nikkei newspaper, 44 percent of Japan’s restaurant operators with outlets abroad are planning to add more, up from 28 percent in the previous survey published last year. Zensho, for example, plans to open 1,450 new shops by next March of which over 90 percent will be located overseas. Meanwhile, Osaka-based Food & Life Companies, best known for its conveyor-belt sushi chain Akindo Sushiro, with more than 1,100 eateries across Asia, entered the US in April.

Awata, however, is convinced that he has the secret sauce to succeed. “We’ve put a lot of thought into how to attract customers," he says. “We work on creating moments that make them think, ‘Oh, that looks good’."

Just before noon on a weekday in May, the lunch crowd had begun to line up outside Marugame Seimen in Tokyo’s Shinjuku office district. The self-service eatery is known for its friendly pricing and such bestsellers as kamaage udon with fish stock-based dashi dipping sauce. But it’s not just about wolfing down cheap eats in a casual setting. An open kitchen allows customers to see the wheat-flour-based Sanuki-style noodles being kneaded, rolled, cut and cooked, making for a visual treat as well as a culinary one.

After collecting their udon, which start at ¥340, or under $3, a bowl, customers can add unlimited free condiments such as scallions and minced ginger, rounding it off with a garnish of crispy tempura bits. There’s more to Marugame Seimen than its freshly made, affordable food, insists Awata. “We’re not just selling a product," he says. “The most important thing is selling the value of the experience."

Emil Fazira, Singapore-based food insights manager at UK research firm Euromonitor International, agrees that this is where the quick-service industry is heading: “Fast and seamless services but at the same time… something unique."

Awata upped the ante recently by deploying menshokunin, or skilled udon masters, at all of his 840 Marugame stores in Japan. To qualify, they were required to pass a test, with only 30 percent making the grade. “With this [attention to the dining experience] as our major competitive edge, we’d like to take on the global market," he says.

To realise that ambition, Awata has earmarked up to ¥100 billion for acquisitions. So far, roughly 20 percent of that amount has been deployed, though the company says it has received over 100 investment proposals from various brands. Meanwhile, Awata has planned more branches for both Marugame and Hong Kong-based rice noodle chain Tam Jai, the company’s two biggest overseas revenue drivers.

In March, Marugame added Canada to its current footprint, which includes Asia (minus mainland China following a disagreement with a franchise partner in 2022), the US and the UK. Tam Jai will open new outposts in Australia, New Zealand and the Philippines by year-end, and Malaysia in early 2025. Toridoll bought Tam Jai in 2018 for $243 million—its biggest purchase to date—and took the company public on the Hong Kong stock exchange three years later, retaining a 74 percent stake.

Aaron Jourden, director of international research and insights at US restaurant-consulting firm Technomic, says by email that while Toridoll has “a strong differentiated brand with Marugame", the company needs Western fast-food chains that serve up fare such as burgers, fried chicken and pizza if it wants to compete with giants like McDonald’s and Yum! Brands.

Awata agrees that noodles are “a little bit niche" while the market for Western fare is much larger. That led him to spend £93 million ($118 million) last year to buy Fulham Shore, the London-listed operator of Franco Manca pizzerias and The Real Greek restaurant chain, with 70 and 26 stores, respectively. Awata wants to take Franco Manca further afield, seeing particular potential for the UK chain, which makes sourdough pizzas from scratch in front of customers and already has a store in Spain.

Hong Kong-based rice noodle chain Tam JaiImage: Courtesy of Toridoll

Hong Kong-based rice noodle chain Tam JaiImage: Courtesy of Toridoll

According to Fulham Shore CEO Marcel Khan, “Awata-san doesn’t invest in any business that doesn’t have an element of kando." The Japanese word denotes a deep emotional connection, a business philosophy Awata shares with other Japanese companies such as electronics giant Sony.

The entrepreneur says that as he battled the odds to create his own venture, he was also inspired by the success of Zensho’s Ogawa, a former labour organiser and shipyard worker, after seeing him featured on a Forbes Asia cover in 2011. Says Awata, “I want to create a globally recognised Japanese restaurant business too."

Awata’s path to entrepreneurship—and to the three-comma club—wasn’t easy. He was 13 when his father died and he was brought up by his mother in Sakaide, a city in Kagawa prefecture. He dropped out of Kobe City University of Foreign Studies to help support the family, and it was while working at a coffee shop that he discovered his calling. “I found joy in cooking, serving dishes to customers and hearing them say how delicious it was," he recalls.

Determined to save up to start his own restaurant, Awata became a truck driver, the highest-paying work he could find, hauling goods around the clock and living in a company dormitory. Life was bleak, he says, but he found solace in the friendly atmosphere of a nearby grilled chicken stand. It inspired him to open his own yakitori restaurant, which he ran with his wife. (Awata says the name Toridoll has no meaning, and he chose it because it’s easy to remember.)

A visit at the end of the 1990s to his late father’s hometown of Marugame in Kagawa, famous for its Sanuki udon made from locally grown wheat, salt and water, gave the budding restaurateur a fresh idea. One udon stall in particular attracted long lines for its noodles cooked in front of customers. The result was the first Marugame Seimen, established in Kakogawa in 2000 (seimen is Japanese for noodle-making).

A Franco Manca pizzeriaImage: Courtesy of Toridoll

A Franco Manca pizzeriaImage: Courtesy of Toridoll

Asia’s bird flu epidemic in 2004 hurt sales at Awata’s yakitori stores, which had grown to dozens by then, and forced him to scrap plans for an IPO. Switching track, he poured his energy into growing the udon restaurants. He opened a noodle stall in a food court because it was a cheap option, then added stands for ramen and stir-fried noodles, realising he could double or even triple his takings in one location by offering different dining options.

Most of this expansion was funded by bank loans and cash flow, until the company was big enough to list in 2006, by which time he had 100 Marugame Seimen outlets. “If the bird flu outbreak hadn’t happened, I wouldn’t have expanded to this extent," he says, “So, it feels like that failure led to a significant success."

The motivation for going global came from a visit in 2009 to Hawaii, where seeing the tourist crowd spurred Awata to launch his first overseas restaurant. That Marugame Udon store, opened in Waikiki in 2011, generates monthly sales of more than ¥100 million, the highest takings among his stores worldwide, according to Awata.

Starting in 2015, he spent upward of ¥9 billion on an acquisition spree, snapping up Netherlands-based Wok To Walk that year (persuaded by the long lines outside its restaurants) a 49 percent stake in the operator of Malaysia’s Boat Noodle chain in 2016 Banpaiya casual bars and Zundo-ya ramen shops in Japan in 2017 and a 70 percent stake in MC Group, operator of Monster Curry in Singapore in 2018.

Like most restaurant companies, Toridoll was clobbered by Covid-19 and swung to a loss of ¥5.5 billion in the year to March 2021. It has since returned to a profit, bolstered by more takeout meals and such initiatives as udon in a cup and its first drive-through store. Takeaway now accounts for between 10 percent and 20 percent of Marugame’s sales in Japan, Awata says, up from around 2 percent pre-pandemic. Awata also keeps an eye on refreshing menus Marugame recently introduced “udonuts", chewy doughnuts made with udon dough, sprinkled with powdered sugar or curry powder.

To stay fit Awata used to run half marathons but now sticks to morning walks, jogging and golf.

He also collects contemporary art, such as the works of Japan-based Chinese artist Lou Zhenggang, known for her abstract monotone paintings. Awata’s art collection grew so large he bought a house in Tokyo’s fashionable Hiroo area and converted it into a private gallery for her works, and added a sushi counter in the basement.

As for the future, he has three adult children but says they are all “doing their own thing", and won’t take over the business. The company says it will announce succession plans at the appropriate time. The chief executive often drops into his restaurants unannounced to sample the food. Most of the time he is unrecognised by the staff and is treated like any other customer. “I sometimes get warned to wait in line… and I do."

Meanwhile, he’s holding onto his dream of building a global food empire. “I have this desire to run a large business," he says. “I don’t want to end here."

First Published: Nov 20, 2024, 13:14

Subscribe Now