In a room filled with artifacts like Dylan’s leather jacket from the 1965 Newport Folk Festival and a photograph of a 16-year-old Bobby Zimmerman posing with a guitar at a Jewish summer camp in Wisconsin, a digital display lets visitors sift through 10 of the 17 known drafts of Dylan’s cryptic 1983 song “Jokerman." The screen highlights typed and handwritten changes Dylan made throughout the manuscripts, showing, for example, how the line “You a son of the angels/You a man of the clouds" in the song’s earliest iteration was tweaked, little by little, to end up as “You’re a man of the mountains, you can walk on the clouds."

The “Jokerman" exhibit is one instance of how the organizers of the $10 million Dylan Center — which opens Tuesday, after a long weekend of inaugural events featuring Elvis Costello, Patti Smith and Mavis Staples — have tried to bring Dylan’s paper-heavy archives to life and entice newcomers and experts alike.

It also points to the center’s larger aim of using Dylan’s vast archive, with documents and artifacts from nearly his entire career, to illuminate the creative process itself. In addition to exhibits focused on Dylan’s work, the two-floor, 29,000-square-foot facility will have a rotating gallery featuring the work of other creators. First up is Jerry Schatzberg, the filmmaker and photographer who shot the cover of Dylan’s 1966 album “Blonde on Blonde."

“We’re really hoping that visitors walk away with a sense that they can tap into their own creative instincts, their own impulse for artistic expression, in whatever medium that might be," Steven Jenkins, the center’s director, said on a recent tour.

![]() Original props belonging to the photographer Jerry Schatzberg sit before a photograph of Bob Dylan holding them during a photoshoot, at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla., April 30, 2022. A new space to display Dylan’s vast archive, celebrates one of the world’s most elusive creators, and gives visitors a close-up look at notebooks and fan mail. (Joseph Rushmore/The New York Times)

Original props belonging to the photographer Jerry Schatzberg sit before a photograph of Bob Dylan holding them during a photoshoot, at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla., April 30, 2022. A new space to display Dylan’s vast archive, celebrates one of the world’s most elusive creators, and gives visitors a close-up look at notebooks and fan mail. (Joseph Rushmore/The New York Times)

The Dylan Center, located at one end of a century-old brick industrial building in downtown Tulsa — the Woody Guthrie Center, devoted to Dylan’s early hero, is at the other — is the museumlike space founded to display items from the Bob Dylan Archive, which was acquired in 2016 by the George Kaiser Family Foundation and the University of Tulsa for around $20 million. (The Kaiser foundation later bought out the university’s share.)

The full archive, with about 100,000 items, is available only to credentialed researchers. It includes huge amounts of paperwork as well as films, recordings, photographs, books, musical instruments and curiosities like matchbooks on which Dylan scrawled a few words. (For fire safety reasons, the matchbooks are kept elsewhere.) Among the many highlights: a newly discovered film soundtrack from 1961 and four typewritten drafts of “Tarantula," the book of disjointed prose poetry that Dylan wrote in the mid-60s.

![]() A metal gate crafted by Bob Dylan welcomes visitors to the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla., April 30, 2022. A new space to display Dylan’s vast archive, celebrates one of the world’s most elusive creators, and gives visitors a close-up look at notebooks and fan mail. (Joseph Rushmore/The New York Times)

A metal gate crafted by Bob Dylan welcomes visitors to the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla., April 30, 2022. A new space to display Dylan’s vast archive, celebrates one of the world’s most elusive creators, and gives visitors a close-up look at notebooks and fan mail. (Joseph Rushmore/The New York Times)

In characteristic fashion, Dylan — fully active at 80, with a tour on the road and a new book coming out in the fall — has stubbornly avoided engaging with attempts to examine his own work, and had no involvement in the center that bears his name, aside from contributing one of his ironwork gates for the entryway. (His business office in New York, however, has been closely involved.) When he performed in Tulsa last month, at a theater just a few blocks away, the Nobel laureate made no acknowledgment of the institution in his honor about to open just down the street.

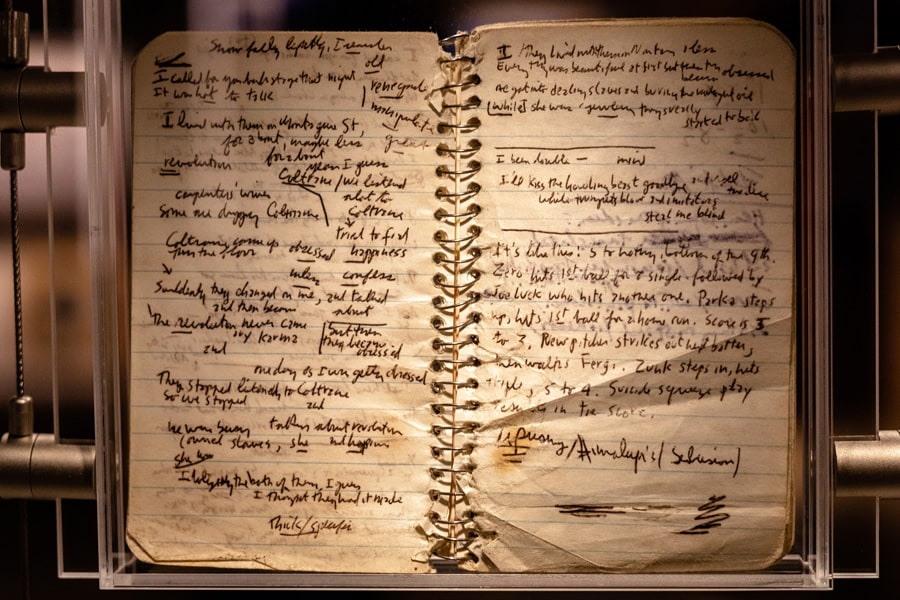

The challenge for the Dylan Center is to make the archive understandable to lay audiences while also drawing on its depths to please the fussiest Dylan experts — the types who may be well-versed on minutiae like the murky provenance of the red spiral notebook Dylan used for “Blood on the Tracks," which is at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York.

![]() A bag of fan mail directed to Bob Dylan in 1966, on display at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla., April 30, 2022. A new space to display Dylan’s vast archive, celebrates one of the world’s most elusive creators, and gives visitors a close-up look at notebooks and fan mail. (Joseph Rushmore/The New York Times)

A bag of fan mail directed to Bob Dylan in 1966, on display at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla., April 30, 2022. A new space to display Dylan’s vast archive, celebrates one of the world’s most elusive creators, and gives visitors a close-up look at notebooks and fan mail. (Joseph Rushmore/The New York Times)

One step was to not call the new facility a museum at all, but rather a “center" that would encourage debate and welcome multiple perspectives.

“I’m more interested in this as a living archive than as a museum," said Alan Maskin of Olson Kundig, the architecture and design firm behind the Dylan Center. “Museum implies a voice that everyone accepts as truth."

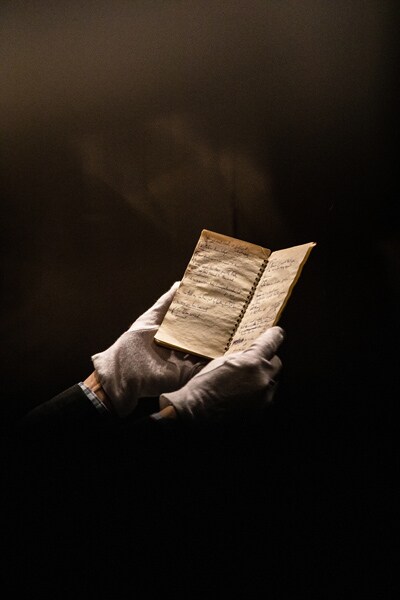

![]() One of three notebooks containing original handwritten lyrics used on the Bob Dylan album “Blood on the Tracks," on display at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla., April 30, 2022. A new space to display Dylan’s vast archive, celebrates one of the world’s most elusive creators, and gives visitors a close-up look at notebooks and fan mail. (Joseph Rushmore/The New York Times)

One of three notebooks containing original handwritten lyrics used on the Bob Dylan album “Blood on the Tracks," on display at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla., April 30, 2022. A new space to display Dylan’s vast archive, celebrates one of the world’s most elusive creators, and gives visitors a close-up look at notebooks and fan mail. (Joseph Rushmore/The New York Times)

Some items, like a duffel bag of fan mail from 1966, deliver an immediate emotional impact. In letters from the beginning of the year, fans plead for photos and autographs as if Dylan were any pop idol. Get-well cards poured in after his motorcycle accident that July. A November letter from a soldier in Vietnam describes a young man hearing “Blowin’ in the Wind" on the radio while mourning three fallen friends in a “blood drenched country."

![]() A prop piano that did not belong to Bob Dylan sits in an immersive gallery that nods at how prolific the singer-songwriter has been over his seven-decade career, at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla., April 30, 2022. (Joseph Rushmore/The New York Times)

A prop piano that did not belong to Bob Dylan sits in an immersive gallery that nods at how prolific the singer-songwriter has been over his seven-decade career, at the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Okla., April 30, 2022. (Joseph Rushmore/The New York Times)

Yet Dylan never read this correspondence. According to Mark A. Davidson, the curator of the Dylan Archive, the bag had apparently sat untouched for years, and when archivists received it, none of the mail had been opened.

The center, and the archive, are already evolving. Exhibits like the jukebox will rotate among guest curators. And the Dylan Archive has been steadily expanding. In 2016, it purchased the original tambourine of Bruce Langhorne, who inspired Dylan’s song “Mr. Tambourine Man." More recently it has acquired extensive collections from Mitch Blank in New York and Bill Pagel, who owns two of Dylan’s childhood homes in Minnesota, as well as books and LPs from Harry Smith, the filmmaker and polymath known for compiling the seminal “Anthology of American Folk Music" (1952).

But market values for music archives have soared, in part as a result of Dylan’s own deal. Davidson said that many well-known musicians have offered to sell their collections, saying, “We want Bob Dylan money." Jenkins, the center’s director, said that while the Kaiser foundation covered about half of its $10 million opening cost — the rest was raised from donors — the institution will seek to establish enough revenue sources to become financially “self-sustaining."