Samhi Hotels: Express check-in

In just under a decade, Samhi has emerged as India's third-largest hotel ownership company

Ashish Jakhanwala, who set up Samhi

Ashish Jakhanwala, who set up Samhi

Image: Amit Verma[br]There is a quiet sense of satisfaction in Ashish Jakhanwala’s voice as he talks about a recent acquisition. In 2017, Samhi, the hotel management company he set up in 2011, acquired Premier Inn’s five properties in India. The hotels run by Whitebread PLC, which operates UK’s largest hotel chain, hadn’t been able to prosper in the Indian market. Jakhanwala, 44, saw it differently: The five properties were located in business centres, such as Kharadi in Pune and Whitefield in Bengaluru the brand was largely unknown in India but with the right marketing (and a name change) tariffs could go up from ₹2,300 a night to ₹3,500.

The hotels were acquired and immediately closed for extensive renovations, which lasted six months. Rebranded Fairfield by Marriott, they reopened with all the amenities a business traveller needs, from fitness centres and wifi, to meeting rooms and car rentals. Tariffs moved up, and mid-week rates for June stood at ₹5,200 at the Bengaluru property, and ₹4,000 for the Pune one. “Though it’s still early days for the acquisition, the initial signs are encouraging,” says Jakhanwala.

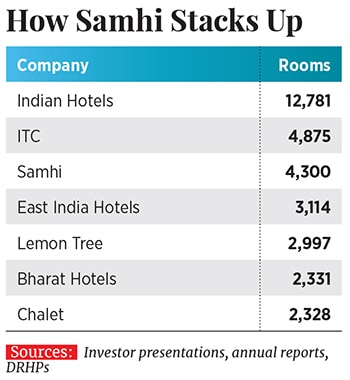

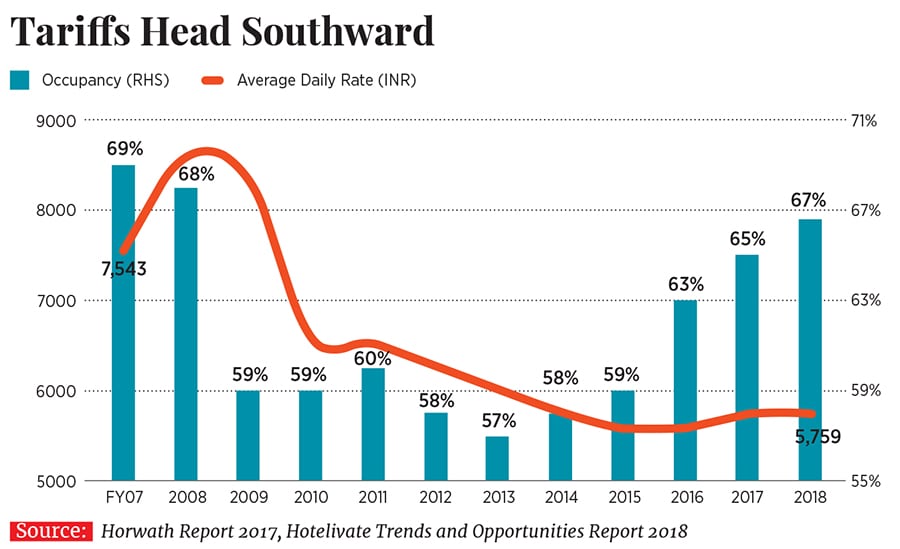

Samhi, with 4,300 rooms, is now the third-largest hotel owner company in India, after Indian Hotels and ITC. Backed by billionaire property investor Sam Zell (Equity International), Goldman Sachs, the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation and GTI Capital, it is agnostic to location, brand and segment and has steadily built its portfolio of rooms in the last five years. Its journey is an apt lesson in how patient capital works, and why investors often need to take a multi-decade approach to the Indian market. In a November 2017 interview with Forbes India, when asked to describe Samhi’s journey, Zell used just one word: “Incomplete”.While a part of Fairfield’s numbers—they are expected to clock 60-65 percent occupancy by 2020—are on account of the new management, equally important is the demand-supply equilibrium the hotel industry finds itself in. After falling off a cliff in late 2008, both occupancies and average room rents have increased. According to the Horwath Report, an industry newsletter, occupancies in FY2018 were at 67 percent, 1 percent below 2008 numbers. The intervening decade saw occupancies fall to as low as 57 percent, dragging tariffs down by 45 percent from their 2008 peak. If current trends continue, the market could witness a supply squeeze in the coming years, with occupancies slated to touch 76 percent in FY2021. “India is underserved by quality hotels,” says MR Jaishanker, MD, Brigade Enterprises, which owns five hotels in Bengaluru, Mysore and Chennai. “In FY19, occupancy rates are up 10 percent and room rates up 7 percent.”

Higher occupancies have also resulted in better operating performance for hotel companies over the last year. In the year ended March 2019, Indian Hotels, which runs the Taj brand, saw profit increase by 189 percent to ₹287 crore. Lemon Tree Hotels saw a 271 percent jump to ₹52.7 crore. With rising tariffs, the industry expects to post better numbers in the present fiscal. The market has also priced in the improvement in performance with their stocks quoting at a PE multiple of between 50 and 80 times. Hyatt Regency, Pune[br]The Early Days

Hyatt Regency, Pune[br]The Early Days

In the decade after he graduated from the Institute of Hotel Management in Lucknow in 1996, Jakhanwala held a variety of jobs—at a management consultancy that planned facilities for hotels, and a part of the team that set up the first hotel for budget chain Ibis in India.

What India lacked in those days was a pure play hotel ownership firm. Constructing hotels from the ground up was, and continues to be, a cumbersome task best left to builders. “Pure play (ownership/management) companies are more respected by investors,” says Jakhanwala. Scaling up is faster, and companies find it easier to distinguish their management skills. But like any hard asset business it is a capital guzzler, and hence initially the ramp-up can be slow.

In 2011, Jakhanwala found himself in New York with a business plan. He’d been introduced to Sam Zell’s Equity International and was clear that he needed long-term investors. (The other initial investor was GTI Capital.) Over a series of meetings over five weeks, Equity International tested the robustness of the business plan, in which Jakhanwala had invested all his personal savings of ₹70 lakh. Finally, Samhi received $70 million (₹350 crore) from Equity International and $30 million (₹150 crore) from GTI Capital.

In the decade till 2010, India’s hotel industry had seen significant oversupply, which distorted the market. Both institutional capital and single hotels set up by high net worth individuals were to blame. Sample this: In 2006, Gurugram had 300 rooms spread across The Trident, The Bristol Hotel and Fortune. When Accor set up Ibis in 2006, the city’s installed room capacity doubled overnight. “This was a story that repeated itself across various micro markets,” says Gyana Das, vice president of corporate strategy at Samhi. Room rentals and occupancies collapsed. (See Downward Slope)[br]With consolidation within the industry, there were rich pickings for Samhi. “We prefer to buy market dislocations and not just distress,” says Jakhanwala, whose team keeps a sharp eye on growth in airline traffic and office space leasing, as well as occupancy trends. They move in on properties when occupancy levels are ideally between 60 and 70 percent.

Further aiding them is the fact that the sector is now capital starved. Banks are unwilling to lend, and although institutional capital is adding rooms, the supply is nowhere near a glut. “In the 2000s, adding 500 to 700 rooms doubled supply in a market. Now with Gurugram having 9,000 rooms and Bengaluru 15,000, the market can easily take in 500-1,000 more rooms a year,” says Rajat Mehra, financial controller at Samhi. For now, the kind of supply needed to disrupt the market is not there, as yields at 6 to 8 percent still don’t justify building new hotels. Sheraton, Hyderabad[br]Acquiring and Branding

Sheraton, Hyderabad[br]Acquiring and Branding

Globally, hotel ownership companies have been market favourites and Host, a Marriott spin-off, manages 100,000 rooms and has a $13.5 billion market cap. On a smaller scale, Samhi aims to recreate this in India.

It’s properties are segment- and brand-agnostic, and cover upscale to budget business hotels. It is market-agnostic too, being present in 14 cities. The only thing it has consciously avoided is to build hotels, which have a three to five-year construction cycle.

Once it acquires an asset, Samhi has a two-pronged strategy to increase room rates (rev par in industry parlance) and optimising costs. Its hotel generates 27 percent of their electricity from renewable sources, and contracts rate with vendors are renegotiated. The rooms are renovated and repriced in accordance with market conditions.

In 2018, with 14 of its 29 hotels shut for renovation, Samhi had a topline of ₹420 crore, with an Ebidta of ₹75 crore. In 2019, with all its hotels open, Samhi has budgeted for a significant increase in topline.

Samhi’s journey shows how patient capital can build sustainable businesses. Jakhanwala, who has so far raised $208 million (₹1456 crore), has also taken debt of ₹1,700 crore. All equity investors, who own 93 percent of the company, have the same rights—there are no different classes of shares—and employees own 7 percent of the company. Equity International and GTI Capital upped their stakes in a second round of financing in 2015.

“The hotel market in India is expected to enjoy a long and strong upcycle, underpinned by domestic tourism and business travel,” says Tom Heneghan, CEO of Equity International. “The structural increase in demand is similar to other markets we operate in, like Mexico and Brazil.”

With 4,300 rooms at an average cost of ₹68 lakh per room, Samhi has scale and a war chest to make more acquisitions. As it moves in to make the most of a cyclical upturn, Jakhanwala is optimistic as there isn’t significant capacity coming in. “There may be minor dislocations in micro markets due to new hotels coming in but the story for the next few years shows rates moving upwards,” he says.

First Published: Jun 25, 2019, 07:24

Subscribe Now