Cover story: How SpiceJet is relearning to fly

Beleaguered with financial problems, SpiceJet is looking to leverage existing revenue streams to stay afloat in turbulent times. But the pandemic may not be the only headwind blowing its way

Ajay Singh, chairman & managing director, SpiceJet, believes India"s aviation sector is bouncing back

Ajay Singh, chairman & managing director, SpiceJet, believes India"s aviation sector is bouncing back

Image: Amit Verma[br] By his own admission, Ajay Singh has always hated living a placid life.

That’s precisely why, every now and then, he relishes taking up new challenges, particularly those that his friends and well-wishers consider impossible. The last time he did so was five years ago when he decided to buy an airline that had nearly gone bankrupt.

SpiceJet, then owned by Tamil Nadu-based billionaire Kalanithi Maran, had to shut operations after debt spiralled out of control. Singh stepped in, bought the controlling stake, and turned in 18 consecutive months of profits. “You know, when I took over SpiceJet, people told me, you"re completely nuts. You"re crazy. This is impossible. It"s never been done anywhere in the world,” says the chairman and managing director of SpiceJet. “For me, it was easier to revive something than to set it up again. It’s all about a never-say-die attitude.”

Perhaps, it’s this attitude that has helped the airline stay afloat despite some heavy tailwinds in the past year, particularly as the coronavirus pandemic ravaged the world. When India announced a two-month nationwide lockdown, and the airline industry came to a standstill, there wasn’t a single day when SpiceJet didn’t operate its aircraft were engaged in transporting medicines, personal protection equipment (PPE) kits, and farm produce. In fact, Singh claims, his airline was the first to approach the government to allow carrying cargo, specifically medical equipment and medicines, on passenger seats.

“There was not a single day when we didn’t speak to the government,” Singh says. “And there was not a single day when we didn"t fly, because we realised that when you take passenger capacity out of the market, goods will still need to flow. Especially during Covid-19, medicines, PPE kits and other such things need to be transported.” In the early days of the lockdown, the airline even took to the skies with just one PPE kit, procured from China and flown to Coimbatore, upon a government directive to help Indian manufacturers make them locally. SpiceJet is betting big on cargo movements and is planning to ramp up its cargo aircraft to 20

SpiceJet is betting big on cargo movements and is planning to ramp up its cargo aircraft to 20

Image: Courtesy Spicejet[br] “We felt very good about that, and we did that at our own cost,” Singh says. “It is so great to be part of a national effort to fight the crisis." Working for the nation perhaps comes naturally for Singh. After all, the 54-year-old engineer-turned-businessman is often perceived to be closely affiliated to the Bharatiya Janata Party, and is often credited with the slogan ‘Ab ki baar Modi sarkar [This time around, a Modi government]’, which the party used while campaigning for the parliamentary elections of 2014.

Over the past six months, the airline has also flown repatriation flights across the world, bringing home more than 1.3 lakh Indians.

These included over 1,000 flights from the Philippines, Russia, Italy, the Netherlands and the Gulf countries. “There were so many Indians stuck around the world,” Singh says. “We just needed to get our people back.” SpiceXpress is the dedicated air cargo service arm of SpiceJet, and the airline believes the demand for pilots will see an uptick over the next one and a half years

SpiceXpress is the dedicated air cargo service arm of SpiceJet, and the airline believes the demand for pilots will see an uptick over the next one and a half years

Image: Courtesy Spicejet[br] Turbulence in the Air

Yet, despite all the heroics over the past few months, it hasn’t been easy for the airline. To begin with, its fleet of 13 new Boeing 737 Max aircraft has been grounded for more than a year. SpiceJet had placed orders for over 200 aircraft, of which 123 were 737 Max variants. These were to become functional between 2018 and 2024 to help expand operations and market share (SpiceJet is India’s second-largest airline by market share).

Boeing’s 737 Max aircraft were globally grounded in March 2019 after more than 300 people died in two fatal air crashes, in Indonesia and Ethiopia, leading to scrutiny of the American aircraft maker’s business practices. The Federal Aviation Administration, US’s civil aviation regulator, subsequently sought changes to the aircraft, updating its software, wiring and crew procedures. Boeing is now targeting to fly the aircraft in early 2021.

“It was an aircraft that was doing wonderfully for us,” Singh says. “And then, it just came to a halt and this is the longest ever grounding in the history of any aircraft. We expect to start flying it early next year. But yes, that put a lot of pressure.”

Then, as the Covid-19 pandemic hit, SpiceJet, in Singh’s opinion, has been subjected to far more scrutiny than its peers, although all of them are reeling under the same problems. In July, the Airports Authority of India (AAI) put the airline on a cash-and-carry mode before revoking that plan a day later. Under a cash-and-carry mode, the credit facility given by AAI is withdrawn, forcing the airline to pay cash upfront for using airports, putting serious financial stress on the airline. Around the same time, SpiceJet"s auditor expressed doubts about its ability to continue operations, as losses in two successive years had led to erosion of its net worth.

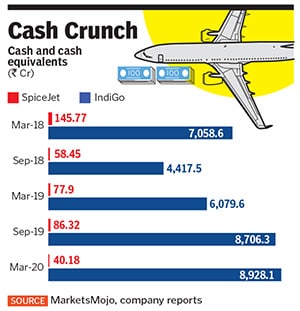

“The overall situation at the airline isn’t quite good,” says an industry insider who didn’t want to be named. “Their cash flow is pretty bad, and they have not been able to raise any cash. There have been reports that lessors are now knocking on their doors to recover aircraft. The million-dollar question is whether the government can afford another airline to fail, especially since it has always enjoyed the blessings of the current government.”

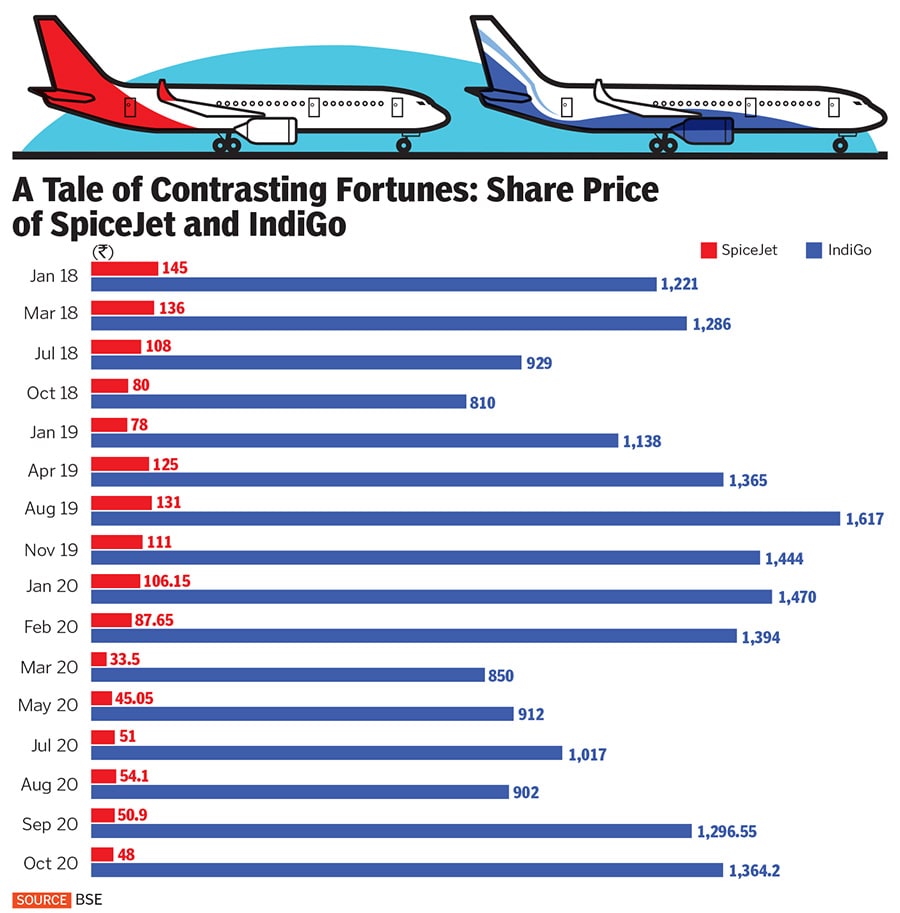

This looming concern is also perhaps why the share price of the company, once the world’s best-performing aviation stock, has taken a severe beating. Between June 2019 and October 2020, it has tanked 68 percent, even as the benchmark Sensex remained rather flat.Shares of InterGlobe Aviation Ltd, the parent company of IndiGo, India’s largest airline by fleet size and market capitalisation, only fell less than 20 percent during the same period.

“Deep down, even institutional investors know very well that it’s not all fine at SpiceJet,” says Mark Martin, founder of Dubai-based Martin Consulting. “Singh has to cough up $100 million for ensuring the upkeep of aircraft. Even that hasn’t happened. He is on the backfoot now.”

In early October, two lessors of the airline, BOC Aviation and Wilmington Trust Services, took the airline to court in London, claiming outstanding dues in excess of ₹200 crore. BOC Aviation has claimed ₹48 crore in dues for rent and accrued interest, while Wilmington Trust Services claim the airline has not paid monthly rent since April 2019 and owes dues of ₹156 crore, including interest.“These relate to the aircraft that have been grounded,” says a company executive on condition of anonymity. “The Boeing 737 Max has been grounded, and since we operate on a sale-and-leaseback model, the grounding wasn’t our fault, and liabilities should be borne by Boeing.” Sale-and-leaseback is an industry term for a transaction that allows a company to lease an airline to itself after selling it to a third party.

Meanwhile, in August this year, Kiran Koteshwar, a veteran at SpiceJet and its CFO, quit and took charge as CFO of Green Africa, a Lagos-based fledgling airline. “Who in their right mind would leave a company that is India’s second-largest airline,” asks another industry insider who didn’t want to be named. “He had seen the airline through the crisis, and the resignation only points to how things aren’t all well.”

In the midst of this, in September, the Delhi High Court asked the airline to deposit ₹243 crore with the court within six weeks in an ongoing arbitration case with its former owner Kalanithi Maran and his company KAL Airways. The case relates to a deal in which Maran transferred his entire stake of 350 million shares in SpiceJet to Singh in return for redeemable warrants of ₹700 crore. SpiceJet has already deposited ₹579 crore with the court.

Singh remains unperturbed. “I can understand what people or competition might have said. SpiceJet is perceived to be a smaller airline, already under pressure for the Boeing 737 Max problem. We were extremely confident that nothing would go wrong, and unlike our peers who didn’t pay anything to their employees [through the lockdown], we continued to pay ours.” SpiceJet also claims that it did not lay off any employees, even as others, including IndiGo, laid off staff.

“I told everybody from day one, we are not going to go down,” Singh says. “We went through a far worse time in 2015. We came out of that.” According to the latest data from India’s Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA), SpiceJet had the highest passenger load factor (PLF) among Indian airlines at over 70 percent in July and August. PLF is an industry term for how much of an airline’s passenger carrying capacity is used.

India has firmed up plans to allow domestic airlines to increase their operations to 75 percent of capacity, with passenger traffic limping back. According to rating agency ICRA, domestic passenger traffic in September stood at 3.9 million, as against 2.8 million in August, indicating a 37 percent growth. “While some airlines have sufficient liquidity or financial support from a strong parentage, which will help them sustain over the near term, the airlines that are already in financial stress are now facing an existential crisis,” ICRA said in a statement. Currently, over 44.01 percent of promoter shares at SpiceJet are pledged.

Perhaps, that’s also why, despite the recent uptick in passenger traffic, Singh isn’t at ease, and is laying out grand plans to de-risk his business, and foray into newer areas and expand SpiceJet into a formidable air transport player.

Firing From All Cylinders

Much of the plan to foray into newer areas comes from a strong belief that being an airline operator alone isn’t sustainable.

India’s aviation industry has been stuck in a rut for a long time, largely due to the very high cost of operations, particularly taxes. “There is a saying that airlines don’t make money but everyone around them do, including infrastructure providers,” Singh says. “SpiceJet certainly wants to see that we are part of the whole game of aviation, and not just in passenger-flying. That also reduces the risk.” For this, he is betting on five different verticals, including cargo operations, maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO), cadet training, air ambulances, and merchandise.“These businesses, which are ancillary, are already a significant part of the revenue,” he says. “So the mix will change.”

The focus, however,will be on the cargo and MRO businesses, which Singh reckons will provide massive opportunity, and are currently dominated by foreign carriers and hubs. Through the lockdowns of the past months, SpiceJet transported about 50,000 tonnes of cargo, which earned significant revenue.

The airline has since been adding to its capacity of cargo aircraft. “We"re the largest cargo operator, and we have been looking at this segment because it"s almost unbelievable that a country of 1.3 billion people had just five freighter aircraft,” Singh says, perhaps referring to BlueDart, for long India’s only air cargo operator with six aircraft. “China has hundreds of these aircraft, the US has thousands. All the stuff that comes into India from different countries, and all the stuff that goes out, is carried by foreign carriers 95 percent of the share is with foreign carriers.”

India’s foreign cargo operators include Qatar Airways, Emirates and Etihad, while the domestic cargo business is dominated by BlueDart and IndiGo, which is also looking to build its cargo play. “It’s a shame,” Singh says. “Why should we have foreigners take our stuff in and out. So, we built a cargo business, and it got a fillip with the Covid-19 crisis.”

SpiceJet has 16 dedicated freight aircraft, including five Boeing 737s and three Bombardier Q400s. The airline recently inducted a wide-body Airbus A340 for long-haul cargo operations, in addition to converting a few of its passenger aircraft for cargo movements. “With 20 dedicated aircraft, we will have the largest cargo fleet,” Singh says. “We have two wide-body aircraft, we are getting a third in October and are trying to add two in November.”

The focus on cargo has begun to show promise, making Q1FY21 revenues jump by 144 percent. “This September, cargo revenue was four times that of last September,” Singh says. “We were close to ₹32 crore, and now we are at ₹125 crore. We have inducted a wide-bodied aircraft, which nobody imaged doing in a situation so bad for the aviation sector.” It has also helped that in September, the government amended its policies to reduce foreign freight charter flights from all airports to just six airports (Delhi, Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, Bengaluru, and Hyderabad).

With tectonic shifts taking place in India’s ecommerce industry, there could be serious merit in SpiceJet’s cargo gamble, industry insiders say. “Undoubtedly, there is a massive opportunity,” says a former vice president at Jet Airways, once India’s largest airline. “Companies like Kingfisher had tried this. But you must have your last-mile and first-mile connectivity integrated so that you can premiumise the operations. There is, of course, huge money to be made, as BlueDart has shown. But you must ensure the 360-degree integration for the business to survive.”

But, there could be more to Singh’s plan than meets the eye. “He is probably looking to hive off the cargo business as a separate entity to raise finance,” says the industry insider quoted earlier. “Banks are refusing to lend right now, and SpiceJet hasn’t been able to show cash flow. That’s where the cargo business comes into play.”

The government has brought down tax on the maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) industry from 18 percent to 5 percent since April. Singh wants to offer MRO services to the defence sector in addition to commercial aircraft

The government has brought down tax on the maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) industry from 18 percent to 5 percent since April. Singh wants to offer MRO services to the defence sector in addition to commercial aircraft

Image: Courtesy Spicejet[br]

Gearing Up For A Challenge

The Gurugram-headquartered company is also trying to emerge as one of India’s foremost maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) player.

Last year, SpiceJet set up Spice Technic, a fully owned subsidiary to focus on the MRO business. “It makes no sense for a country like India, which has such a fast-growing aviation sector, to send its aircraft overseas for repairs and checks,” Singh says. “So we set up Spice Technic a year or so ago, and we started to do most of the C-checks in-house.” A C-check is an extensive list of checks of systems and components, and is undertaken every 18 to 24 months.

Although India had long been touted as a potential hub for MRO operations, the sector had been stuck in a quagmire, mostly because of high taxes. The government pegs the industry at $900 million (₹6,608 crore), expects it to grow to $4.33 billion (₹31,500 crore) by 2025, growing 15 percent annually. According to the Economic Survey for 2019-20, the annual import of MRO services by Indian carriers was estimated to be around ₹9,700 crore.

“The problem was partly with taxation, but the government has helped rectify a lot of it,” Singh says. “We have been telling them this is a labour-intensive business. India should be the MRO capital of the world, but Indian carriers are sending their aircraft to different parts of the world.” Until this March, MRO services were taxed at 18 percent, after which rates were brought down to 5 percent.

India is expected to need 2,380 new commercial airplanes, worth $330 billion, over the next 20 years, says Boeing. To operate and maintain these, operators are expected to spend $440 billion on services, including maintenance and engineering, providing a massive impetus to the domestic MRO sector.

SpiceJet also senses an opportunity in targeting MRO services for fighter and transport aircraft of the defence forces. Although this aspect of the business was set up six months ago, Singh thinks it could take some more time to take off: “In our business, we can’t have one aircraft out of service for too long. In the defence sector, the time frames are more flexible. But there is no reason why there should be a wall between civilian and defence aircraft.” So, for now SpiceJet wants to cater to commercial airlines in Southeast Asia, before branching outward.

Experts, however, feel things will not be easy. To begin with, the company claims to have two MRO facilities, one each in Chennai and Gurugram. “They have converted hangars and are claiming those to be MRO facilities,” says the industry executive quoted earlier. “It is a capital-intensive business, and nobody, not even the defence sector, will think of sending their aircraft to them. As it is, the Air Force is never dependent on private contractors, and even if they were, Hindustan Aeronautics Limited will have a role to play.”

Besides, for a cash-strapped airline, setting up an MRO business won’t be easy. “Entry into fields like MRO requires massive investments, coupled with talent that is familiar with on-ground challenges,” says Satyendra Pandey, a partner at advisory firm AT-TV and former head of strategy at GoAir. “On that front, several questions remain. All too often, the industry has resorted to hiring consultants who bring in academic views that are not implementable and are at odds with reality. A foray into such a space has to be planned and thought out, especially given that returns in many cases don"t even cover the cost of capital. It is no coincidence that private equity, financiers and existing players have been reluctant to enter this sector.”

Going Beyond the Usual

SpiceJet is also trying to bring in business from its aviation academy and an air ambulance business.“Temporarily there is a problem, because airlines don’t need pilots or they need fewer pilots than before,” says Singh, about the potential of the academy, which is often a money churner, largely because it includes upfront payments from candidates. “We were on a massive growth trajectory a lot of people wanted to be pilots. In a year and a half, we have to start planning again for future growth.”

That’s also how long Singh expects it will take for the industry to recover from the ongoing crisis. India had shut down air travel in March, before resuming it in May, at just 33 percent of existing capacity. “I think it"ll take another couple of years,” he says, about the time it would take India’s aviation sector to return to a period of growth. “The bounce-back has been a little faster than we expected we didn’t expect to be at 50 percent. What is now uncertain is international travel.”

In early October, the airline announced plans to launch services to London, at nearly half the existing fares, as part of an air bubble between India and the UK. Air bubbles allow designated airlines of two nations to fly passengers either way without any restrictions. In August, SpiceJet had secured slots at London’s Heathrow airport to operate flights from September 1.

Now, Singh and his team are laying out plans to ramp up international operations. “We are looking for opportunities,” he says. “Can we fly more international? What is so sacrosanct about a long-haul flight? The cost was high, but now it"s lower.” This decline is largely due to a steep fall in oil prices that have brought down aviation turbine fuel (ATF) prices. ATF prices, which constitute about 40 percent of an airline’s operational cost, was ₹39,000 per kilolitre this September, compared to over ₹64,500 this January.

“During this pandemic, the government has been a little more proactive about structural problems that the aviation industry faces,” Singh says. “Everybody is now talking about the importance of aviation and connectivity. Secondly, the crisis has forced people to re-evaluate how our policies compare with other countries.”

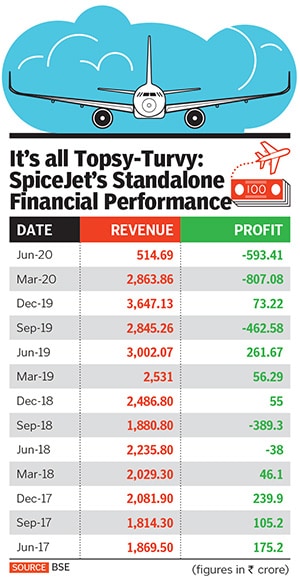

Meanwhile, the ongoing crisis has allowed the airline to renegotiate some of its contracts, particularly of aircraft lease, engineering and maintenance, to lower expenses. “This is the time when you can renegotiate contracts,” Singh says. “The crisis can help get you to a level that makes the company profitable for several years.” SpiceJet has incurred a net loss of nearly ₹600 crore between this April and June.

Its net worth, which was already negative, dipped further to ₹2,170 crore, as on June 30, 2020.

“When it comes to SpiceJet, I am not clear what is their focus,” says Bhavin Shah, founder and fund manager at Sameeksha Capital, an Ahmedabad-based wealth management company. "They did have a strong opportunity to be a number two, low-cost carrier in India. But their financials are far more precarious compared to IndiGo. The Boeing 737 Max crisis affected them, and perhaps they did try to expand a bit too fast. On cash reserves, whether it is ₹40 crore or ₹70 crore, having very little cash clearly puts them at a very high risk of running out of money.”

Singh says he has his hands full with the passenger airline, cargo business, MRO, and the ancillary services. But for a company that has remained India’s second-largest airline for a while, it is surprising that its market share hasn’t exceeded 15 percent over the past few months. “The market share will go up as new aircraft come,” he says. “It’s a function of capacity.”

Singh remains optimistic, and ready to take up a challenge. “I think the landscape will change. India has a fantastic opportunity because unlike other countries, its aviation sector is bouncing back. That gives us a lot of leverage with OEMs and lessors. We just need to set up the infrastructure and lower costs. But this is the very first time I"m seeing actual action on the ground… We have only ourselves to blame if we can"t make the most of this.”

First Published: Oct 26, 2020, 13:37

Subscribe Now