Where are India's TikTok stars headed?

Many new short video platforms have sprung up since the ban on Chinese apps, and are vying for the loyalty of former TikTok stars. But how many will survive?

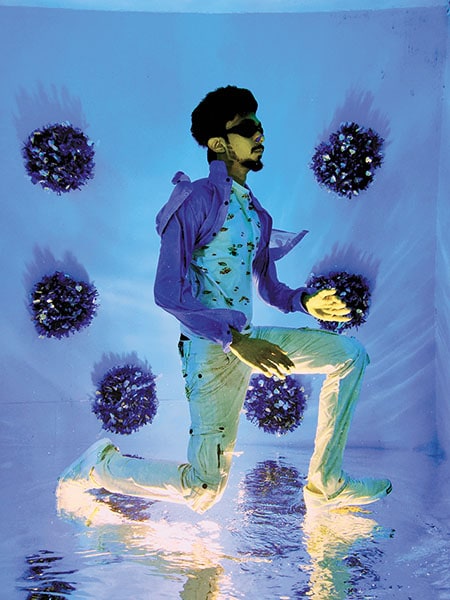

Jaydeep Gohil, better known as Hydroman on TikTok, shot to fame when he posted a video of himself dancing underwater. After practising in a swimming pool in his hometown of Rajkot for almost a year in 2012, Gohil convinced his father, a businessman, to build an over-the-ground concrete tank at home. “In the pool I could only practice for one hour, after that the next batch of swimmers would come in,” says the 25-year-old.

His father agreed and when he saw what his son was up to, thanks to an underwater camera, he was taken aback. Within a year, he bought him a 10,000 litre glass tank to let people see his moves live. In 2015, Gohil entered the India’s Got Talent competition and made it to the semi-finals. Since then he’s been touring cities across India with live performances.

In early 2019, Gohil came across TikTok and decided to post a video on it “just for fun”. The video showed him dancing underwater to a peppy Bollywood tune, surfacing every now and then to breathe. Within minutes, the video went viral. “I then put up more videos, and all of them went viral,” says Gohil. He’s since showcased acts like cutting and eating fruit underwater, playing with a basketball, strumming a guitar, dressing up like a superhero, and frolicking with fish. His unique performances helped him amass 5.6 million followers on TikTok, and collaborations with brands such as Pepsi, Tide and Idea.

With TikTok now banned in India, along with 59 other Chinese apps, owing to data security concerns, Gohil faces an uncertain future. “This is all I’ve done since I completed my Class 12,” he says. Yet he’s optimistic. “Other platforms will come up and I’ll rebuild my fan base.”

Sure enough, a handful of Indian platforms have sprung up since the ban was announced. Chingari, Mitron, Rizzle, and InMobi-owned Roposo, which has made a comeback since its initial launch in 2014, are all vying to fill the gap left by TikTok. The ByteDance-owned, Softbank-bankrolled app had claimed 200 million downloads in India, representing its largest user base outside of China.

Local language social media platform ShareChat launched Moj—its TikTok-like offering—within 36 hours of the ban and is nearing 20 million downloads already. Even Facebook-owned Instagram launched Reels, a short video offering, 10 days after the ban was announced. According to a key TikTok influencer who chose to remain anonymous, Instagram had reached out to him and several other top TikTokers right after the ban. “They told us not to join any other platform as they would be coming out with one in a week or so,” he says. “I don’t want to move to any new platform in haste. If all the good video creators come together and go to one app, that’s better for all of us. So I’d rather take my time, think it through and go to a platform where my brand value will not diminish.”

Geeta Sridhar, or ‘Geeta Ma’ as her 1 million fans on TikTok knew her, used to post Tamilian cookery videos. She was a MasterChef India finalist in 2014 and started blogging after the competition on the insistence of her daughter. She soon discovered TikTok, and became an “addict”, she says. She used to earn ₹50,000 to ₹60,000 per month through brand collaborations, but more than that she says, the love she received from her followers was what kept her going. “Sometimes I would post 13 to 14 videos in day. I loved the platform so much,” she gushes. Like Gohil, she says she supports the ban on TikTok, but misses the platform. “I started using Chingari, but I exited it in hardly a day. On Instagram also, I barely get a five to 10 likes for my videos, whereas on TikTok I got thousands. It’s difficult to match the features of TikTok,” she says.

“For a video app to be successful, it needs velocity and virality,” says Sanjay Mehta, founder of early stage fund 100X.VC. “By velocity, I mean paid growth is needed to get traffic on the platform. That requires huge amounts of capital. Second, virality is needed so that the network effect kicks in.”  Jaydeep Gohil performing one of his underwater acts[br]According to one industry insider who spoke to Forbes India on condition of anonymity, ByteDance “literally threw money at people” to grow the platform. “They were desperate for the Indian market. They spent as much as $20 million to $30 million a month,” he says.

Jaydeep Gohil performing one of his underwater acts[br]According to one industry insider who spoke to Forbes India on condition of anonymity, ByteDance “literally threw money at people” to grow the platform. “They were desperate for the Indian market. They spent as much as $20 million to $30 million a month,” he says.

Without that kind of capital, most apps that have sprung up in the recent past will fizzle out, he adds. Or they might pivot to some other business, like video gaming and eventually sell out, given that many already claim to have garnered millions of downloads.

“Only one or two players can take the pole position in this market,” says Mehta. “Once those winners become clear, capital will flow to them, but until then I have my doubts as to how much money Indian venture capitalists will put into this space.”

*****

This isn’t the first time TikTok has run into controversy in India. It drew scrutiny last year for encouraging pornography, inciting religious hate and promoting data theft. The app was briefly banned in April 2019 by a court order, which was then reversed. In July 2019, three of TikTok’s biggest stars were arrested after they posted a video on the death of a Muslim man. Later that month, the company announced it would set up a $100 million data centre in India to allay the government’s security concerns.

Moni Kundu, an accounts officer-turned-homemaker, supports the government’s decision to ban TikTok and other Chinese apps. She started using the platform as a means of entertainment after leaving her job at an MNC, following the birth of her child. Her now six-year-old son often features in her comic videos that have attracted the attention of brands like Parachute, Emami and Nivea Cream.

“Initially we would do it for our own amusement and family fun. It was effortless,” she says. But when—within a month of joining TikTok in August 2018—her videos went viral, she started looking into it more seriously. She taught herself how to edit videos, add sound bytes and mix music. She also researched how people were monetising the platform.

Just before the ban was announced, Kundu had 6.2 million followers on TikTok and 100,000 on Roposo, which she joined around the same time as TikTok. However, since the ban, her Roposo followers have jumped to 400,000. “Rebuilding my fan base will, of course, take time,” she concedes. “But I believe in focusing on the positive. Platforms will keep changing, but our talent remains. We’ll move on.”

First Published: Jul 16, 2020, 12:36

Subscribe Now