"We have 30 extra years": A new way of thinking about aging

People around the world are living, working, and learning longer. Get ready to upgrade your old ideas about longevity

As one of three co-teachers of a Stanford Graduate School of Business course on the rapidly growing importance of older consumers and workers, Rob Chess likes to say that his colleague Laura Carstensen, the founding director of the Stanford Center on Longevity, is the expert on aging his fellow lecturer in management, Susan Wilner Golden, has the entrepreneurial angle covered and he represents the demographic in question. “I just got my Medicare card," he says with a chuckle.

A serial entrepreneur who has founded and led several successful biotech companies, Chess is having a bit of fun at his own expense. But the growing cohort of older adults he belongs to — and the opportunity it represents — is no joke.

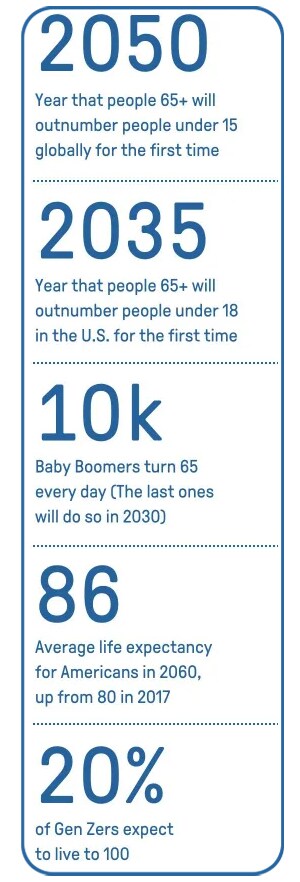

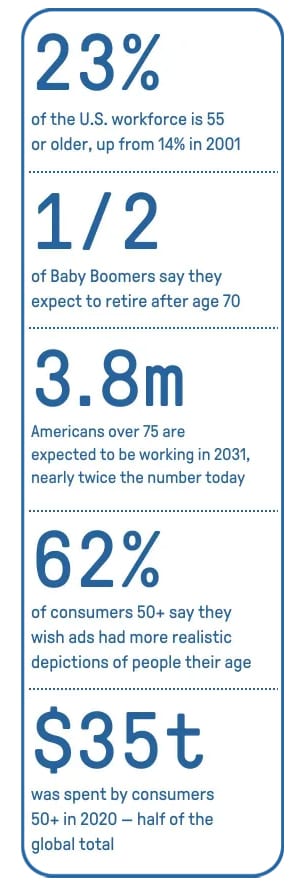

Thanks to advances in medicine and public health, people are living longer, healthier lives. The world’s population of people 60 and older is growing five times faster than the population as a whole. Global life expectancy has doubled since 1900, and experts say that children born in developed countries now have a good chance of living to 100. A “silver tsunami" is already sweeping the U.S. labor force: the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that 36% of people ages 65–69 will remain on the job in 2024 — up significantly from the 22% who were working in 1994.

These longer-lived, longer-working individuals generate an ever-bigger slice of global GDP and control an expanding tranche of global wealth. In her recent book Stage (Not Age), Golden estimates that the “longevity economy" is worth more than $22 trillion — $8.3 trillion in the United States alone. That may be a conservative figure: AARP (the organization formerly known as the American Association of Retired Persons) estimates that people over 50 already account for half of consumer spending worldwide, or $35 trillion. (This range of figures may have to do with how “older adult" is defined: The term is variously used to refer to people over the ages of 65, 60, or — sorry, Gen Xers — 50.)

Yet the longevity market remains untapped by many businesses, which continue to ignore older consumers in favor of younger ones. “People 50 and older hold the vast majority of wealth in the country, but we’re producing products and services for people who don’t have nearly as much money to spend," Carstensen says.

Firms that do attempt to court older adults often fail to understand them. The situation reminds Chess of the computer industry in the early 1980s. At the time, he recalls, most people were focused on hardware. As a result, those who saw the potential market for software reaped outsize rewards. “The people who recognized that early ended up being massive winners," Chess says. He sees a similar opening in the longevity market. “most people’s instincts are to focus younger, when the opportunity really is to focus older."

Of course, older people do more than just buy stuff. Carstensen contends that virtually every aspect of our lives will be affected by our increasing longevity. “The world we live in was literally built by and for young people," she says yet for the first time in history, it now contains comparable numbers of toddlers and octogenarians.

As people enjoy longer, healthier lives, many will have to rethink their educational, career, and retirement paths. Organizations, meanwhile, will have to reconsider how they recruit, retain, and manage employees. That will require us to grapple with deeply ingrained ageism — a prejudice that Jeffrey Pfeffer and Ashley Martin, GSB professors of organizational behavior, describe as “the last acceptable ism."

The rewards for doing so, however, are potentially vast. “This is a unique and unprecedented opportunity," Carstensen says. “We have 30 extra years. How could we use those years to improve quality of life at all ages?"

Engaging with older adults as consumers and workers can be complicated, partly because they are so diverse, ranging from people in their 60s who experience mental and physical decline to “super-agers" who are still working full-time or running marathons well into their 80s. “The population 65 and over is more heterogeneous than any other age group," says Carstensen, a professor of psychology at Stanford who has cotaught the GSB course on longevity for several years. “We can make some really good, informed guesses about what 5-year-olds are like. Try to do that for 80-year-olds it doesn’t work."

Instead of segmenting older people into age brackets, Golden suggests looking at what stage of life they’re at. This may challenge many assumptions about how our lives will unfold. She argues that the linear three-stage model of “learn, earn, retire" is based on outmoded ideas about lifespan and “health span": If you’re going to live to 80 or 90 in relatively good health, it makes no sense to assume that your formal education should end in your teens or twenties or that you should retire at 65.

Instead of segmenting older people into age brackets, Golden suggests looking at what stage of life they’re at. This may challenge many assumptions about how our lives will unfold. She argues that the linear three-stage model of “learn, earn, retire" is based on outmoded ideas about lifespan and “health span": If you’re going to live to 80 or 90 in relatively good health, it makes no sense to assume that your formal education should end in your teens or twenties or that you should retire at 65.

Instead, many older people will likely cycle through a variety of nonsequential and potentially overlapping stages: working for a while, taking a break to raise kids, going back to work in a new role, taking another break to care for parents, retraining and reentering the workforce, taking another break to pursue other interests or additional education, and so on. An 80-year-old and a 40-year-old may occupy the same stage, and a 70-year-old may occupy several different stages simultaneously. Consider Golden’s own trajectory thus far: She earned a master’s in public health and a doctorate in health services, taught at Boston University Medical School, and had a successful career in venture capital before leaving the workforce to raise her daughter and care for her mother. She then returned to school at age 60, becoming a fellow at the Stanford Distinguished Careers Institute while her daughter was a freshman in college.

Yet while older people appreciate not being crammed into a one-size-fits-all approach, openly acknowledging their age can be touchy. As Chess points out, older adults don’t like to be treated as such. “People who are 70 or 80 don’t want to be marketed to as 70 or 80," he says. Consequently, he advocates for “stealth design": crafting products and services with older consumers in mind, but keeping the demographic targeting on the down-low. Ideally, this appeals to older folks without alienating younger ones who might be turned off by products and services that they associate with their parents and grandparents.

Infographic with the following statistics: 23% of the U.S. workforce is 55 or older, up from 14% in 2001. One half of baby boomers say they expect to retire after age 70. 3.8 million Americans over 75 are expected to be working in 2031, nearly twice the number today. 62% of consumers 50+ say they wish ads had more realistic depictions of people their age. $35 trillion was spent by consumers 50+ in 2020 — half of the global total.

Chess points to how BMW used research by MIT’s AgeLab to redesign the controls of some of its high-end sedans. Though you might guess from the automaker’s ads that its cars are meant for 30- or 40-somethings, the average Beemer buyer is 55 or older. Heterogeneity notwithstanding, most people experience joint stiffness and loss of visual acuity as they age. BMW’s new controls, which feature bright primary colors and larger, easy-to-manipulate dials, are more user-friendly for older drivers yet still enjoyable for younger ones.

Similarly, in recent years Merrill Lynch has revamped its approach to wealth management, moving from traditional retirement planning to a stage-based approach that employs teams of advisors to serve multiple generations within the same family. The company also pioneered the use of specially trained “financial gerontologists" to assist clients with issues like cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. As Carstensen and Golden detailed in a 2019 articleopen in new window in Harvard Business Review, this shift in strategy improved customer acquisition, retention, and satisfaction.

Especially as careers last longer, older people can play a valuable role in designing and marketing products for their age-mates: identifying features that might attract folks in their 60s or 70s, for instance, or pointing out when a product intended for Millennials might appeal to Baby Boomers as well. “The common theme in the longevity industry is ‘designed with, not for,’" Golden says.

Distribution can also be challenging. Golden says there is a dearth of marketplaces for longevity-related services like caregiving and continuous learning. Chess points out that customer acquisition costs can be high in areas like home healthcare and end-of-life care, where need is difficult to predict and repeat customers are few and far between. “You don’t buy a funeral more than once," he says.

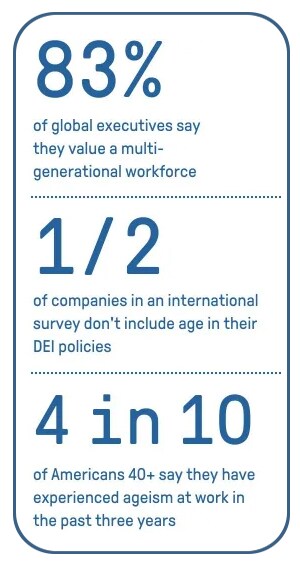

If increasing longevity has the potential to remake the world of products and services, it has similar implications for the workplace. For example, age-diverse teams will become more common. And that is good for many reasons. Research by organizations such as AARP, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the World Economic Forum indicates that multigenerational teams perform better and create stronger talent pipelines.

That’s not to say there won’t be problems. With four or even five generations working together in close quarters, the potential for intergenerational conflict will inevitably increase. According to Carstensen, more research is needed to understand the optimal composition of mixed-age teams so that managers can create environments where age diversity improves performance rather than generating friction. “The devil is in the details," she says.

That’s not to say there won’t be problems. With four or even five generations working together in close quarters, the potential for intergenerational conflict will inevitably increase. According to Carstensen, more research is needed to understand the optimal composition of mixed-age teams so that managers can create environments where age diversity improves performance rather than generating friction. “The devil is in the details," she says.

Businesses will also need to revamp their benefits, compensation, and HR policies to attract and retain employees who are more likely to take career breaks. Research by ManpowerGroup indicates that 57% of male Millennials and 74% of female Millennials already anticipate taking such a break to provide childcare or eldercare or to support a partner.

In 2008, Goldman Sachs and Sara Lee introduced corporate “returnships" — return-to-work programs for people with previous experience who have spent time outside the workforce. Since then, more companies, including heavy hitters like Amazon, Apple, and Facebook, have launched similar efforts. They remain in the minority, however. Carol Fishman Cohen, the co-founder of iRelaunch, a platform that promotes midcareer reentry programs, notes that fewer than 10% of Fortune 500 companies had one in 2021.

Fully embracing older adults in the workplace will also require confronting an old bias: age discrimination. Jeffrey Pfeffer, who is widely credited with inventing the field of organizational demography, wrote a prescient 1979 paper about the impact that an aging workforce could have on organizations. While acknowledging that a “general prejudice against age" was evident in many aspects of American culture at the time, he speculated that the situation might improve as the average age of the workforce increased.

Four decades later, unfortunately, that prejudice shows little sign of abating. “I think there’s actually more ageism," says Pfeffer, who has written about the age discrimination he began experiencing in his professional life when he entered his 60s. (He’s now 76.) “It’s perfectly acceptable to make comments about age that you would never make about any other social category," Pfeffer says.

The federal Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 protects people who are 40 or older, yet it remains difficult to enforce. A survey by AARP found that 61% of adults over age 45 had either seen or experienced age discrimination in the workplace. Nearly one-fifth of the more than 61,000 charges filed before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 2021 were age-related, with research suggesting that many more cases go unreported.

The federal Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 protects people who are 40 or older, yet it remains difficult to enforce. A survey by AARP found that 61% of adults over age 45 had either seen or experienced age discrimination in the workplace. Nearly one-fifth of the more than 61,000 charges filed before the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 2021 were age-related, with research suggesting that many more cases go unreported.

Ashley Martin has found that even people who strongly advocate for gender and racial equality in the workplace still engage in “succession-based ageism," the belief that older workers should step aside to make room for others. Otherwise fervent egalitarians legitimize this bias by arguing that older workers prevent younger people, women, and members of marginalized groups from moving up — even though older workers are a disadvantaged group.

Because it is more widely tolerated than other forms of prejudice, ageism may prove particularly difficult to root out. Age is rarely addressed in diversity trainings or mentioned in corporate diversity, equity, and inclusion policies. According to Martin, fewer than 20% of diversity statements recognize age. “The fact that we’re not talking about [ageism] enough makes it such that we’re not going to find productive ways in which to solve it," she says.

Yet the tools to combat ageism may already exist. Martin’s research indicates that age-related bias tends to abate when people come to understand that older adults aren’t necessarily staying on the job simply because they enjoy working but also because many cannot afford to retire. This, in turn, suggests that ageism may be amenable to targeted interventions — though Martin is quick to point out that all-purpose DEI initiatives are unlikely to solve the problem. Rather, organizations need to understand the specific attitudes their employees hold about older adults, and how (or even if ) those attitudes affect the workplace. “In order for diversity trainings to be effective, you really need to understand people’s beliefs in the first place," she says.

Pfeffer, meanwhile, argues that legal pressure should be used to persuade organizations to take ageism seriously. “I’m a huge believer in litigation," he says, adding that much of the progress made in the fight against racial and sexual discrimination was accomplished through the courts. “The point is just to raise the cost of this form of discrimination."

Carstensen thinks that the problem of ageism is best addressed by building a world where people of all ages can be fully engaged with and integrated into the workplace, the home, and the broader community. “We have so many things we could do to make life better, and not just for old people: for children, for their parents, for workers and employers," she says. Businesses can play a vital role in that process if they have the foresight to make longevity part of their overall strategy.

And given the speed at which demographic change is occurring, they had best begin doing it soon. “As important as it is now," says Chess, “it’ll be vastly more important in 2030."

First Published: Sep 05, 2023, 13:21

Subscribe Now