Make in India: How HAL is gearing up to deliver

The government-owned defence company wants to ramp up manufacturing of aircraft, but it will have to address concerns like production delays and accidents

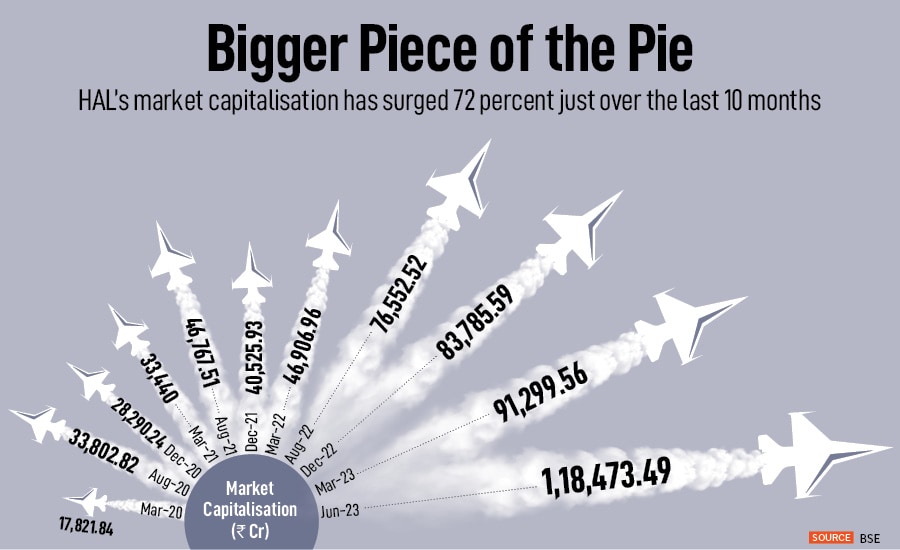

CB Ananthakrishnan finds himself in an enviable spot. In the ten months since he took charge as the chairman and managing director of the public sector defence manufacturer, Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), the company’s market capitalisation has surged a stunning 72 percent. From Rs67,000 crore in August 2022, the Bengaluru-headquartered HAL is today well worth over Rs1.1 lakh crore, making it the country’s largest public sector defence company by market capitalisation.

That’s a far cry from three years ago, when that number stood at around Rs20,000 crore for the country’s largest manufacturer of aircraft, helicopters, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and aerostructures. “Investors have started feeling that this company is offering consistent growth and also see a lot of visibility with the Atmanirbhar Bharat initiative," Ananthakrishnan, who also serves as the director for finance at HAL, says. He joined the company in 2004 as a chief manager, before rising to become the chairman in August last year.

The change in fortunes is most certainly reflective of HAL’s reinvigorated focus on building in-house capabilities as is with a change in the Indian government’s defence procurement strategy, pushing for greater indigenisation. “The defence industry is going through a change and HAL being the lead agency in the industry for almost eight decades is having much better days," Ananthakrishnan says.

HAL is India’s oldest aircraft manufacturer and over the past eight decades has built aircraft ranging from the Sukhoi Su-30 MKI to the MiG-21 and MiG-27 under a licenced program. It has also been at the forefront of manufacturing helicopters and trainer aircraft for the Indian defence forces, in addition to building aerostructures for the Indian Space Reseasrch Organisation (ISRO) and global original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) like Airbus and Boeing.

“Almost 80 percent of the fleet of the defence forces is either supplied by HAL or serviced and supported by HAL," Ananthakrishnan says. In all, the company has manufactured over 4,100 aircraft and over 5,000 engines while overhauling 11,000 aircraft and 33,000 engines across its 20 production divisions and 11 research and design centres spread across the country.

But 2023 is a rather different year for the aircraft maker. It is the first time in decades that the company’s licenced production is limited to a single aircraft, the 19-seater DO-228 aircraft after it completed the manufacturing of Sukhoi Su-30 MKI. Instead, HAL has now turned all its attention to manufacturing its own indigenous products ranging from the Tejas fighter aircraft to four different types of helicopters while also designing and developing a new range of helicopters and fighter aircraft, which will see the government-owned defence manufacturer having a strong pipeline at least until the end of the decade.

“We were into license production earlier," Ananthakrishnan says. “Now there is a range of products which has been indigenously designed and developed by HAL."

The LCA Tejas aircraft has been in the works for nearly three decades before the company received final clearance from the Indian Air Force to be inducted into its fleet in 2019. Similarly, it currently makes four different kinds of helicopters ranging from the Light Utility Helicopter (LUH) to Light Combat helicopter (LCH) and two variants of Advanced Light helicopters (ALH). “This is a really good beginning," Ananthakrishnan says. “With the projects which are lined up for the future in the next 10 to 15 years, the country will become more self-sustainable and self-reliant."

“HAL is the largest defense manufacturing entity in India and will likely remain so for at least the next two decades," says Sourabh Banik, project manager, aerospace and defense at London-based consultancy, GlobalData. “Its product portfolio includes all types of airborne platforms, ranging from fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters to UAVs (Unmanned Aerial vehicle). Although HAL has its challenges and has been time and again scrutinised over delays in deadlines and quality issues, it still has a big order book and a promising product development roadmap to bank on."

Since the new company was set up, much of its attention turned away from indigenous development to licenced manufacturing. These included the Jaguar, Mig-29, Sukhoi-30, Hawk MK-32, and AN-32.

In the six decades since the merger, the company has only been able to indigenously develop one fighter aircraft (Tejas) and four helicopters, two of which are iterations of the base model. Of this, the Tejas fighter aircraft was initially conceived in the early 1980s but had faced multiple headwinds before its induction into the Indian Air Force in 2019. A typical production cycle involves the design and development phase before prototypes are built and tested. That’s followed by a limited series production and a full series production.

So far, the company has delivered 32 of the 40 Tejas aircraft that were supposed to be delivered to the Indian Air Force, and HAL is looking to supply the remaining eight in the current financial year. Post that, the company is set to manufacture 83 Tejas Mk 1A aircraft, while also starting the design and development phase for the Tejas Mk2 aircraft. The Mk1 A is designed as an interim aircraft between the Mk1 and Mk2, with features such as air-to-air refuelling, advanced avionics, and electronic warfare suites. HAL plans to complete the delivery of the Mk1 A by 2028 with an ambitious target of inducting the Mk2 by the same year.

So far, the company has delivered 32 of the 40 Tejas aircraft that were supposed to be delivered to the Indian Air Force, and HAL is looking to supply the remaining eight in the current financial year. Post that, the company is set to manufacture 83 Tejas Mk 1A aircraft, while also starting the design and development phase for the Tejas Mk2 aircraft. The Mk1 A is designed as an interim aircraft between the Mk1 and Mk2, with features such as air-to-air refuelling, advanced avionics, and electronic warfare suites. HAL plans to complete the delivery of the Mk1 A by 2028 with an ambitious target of inducting the Mk2 by the same year.

To do all that, the government-owned company plans to ramp up its production from eight aircraft a year to 16, which could go up in the final year of delivery. The Indian Air Force wants to build six squadrons of the Tejas Mk 2 and the prototype is expected to be tested in 2026.

Then, there is the helicopter division where the company has indigenously developed four helicopters including the Dhruv, Rudra, and Prachand. Dhruv, the first of those was designed and developed in 1984 but took almost two decades before it was inducted into the defence forces. Rudra was inducted in 2013, while Prachand was inducted in 2022. Prachand will replace the nearly 400 Cheetah and Chetak helicopters which have been there in service for decades. HAL expects their delivery to start by next year.

Yet, over the years, the aircraft maker’s reputation has been tarnished by accidents involving some of the aircraft and helicopters that it built. For instance, HAL has built over 335 Dhruv helicopters that have logged over 3,40,000 flying hours. About 20 of them, including the Rudra (an armed version of Dhruv) have met with accidents, killing several on board in addition to causing emergency landings. Currently, over 300 Dhruv Helicopters are in use in the country.

This year, the Indian Army grounded its entire fleet of Dhruv helicopters after a crash in Jammu and Kashmir, while the Bengaluru-based Centre for Military Airworthiness and Certification (CEMILAC) wrote to the three services and the coast guard seeking a design review of the “safety-critical system" on board the helicopter.

“The ALH has been plagued by a series of mishaps since its inception," says Banik of GlobalData. “Apart from domestic users, even foreign users suffered the brunt of these mishaps. In 2015, Ecuador terminated a contract with HAL after four of the seven ALH platforms it purchased from the company got involved in crashes."

That has meant that the aircraft manufacturer has lost out on lucrative export contracts, even as recently as this year when the Malaysian government decided to partner with Korea Aerospace Industries, South Korea’s sole aircraft manufacturer, for the procurement of 18 fighter jets in a deal worth $920 million. HAL had offered the Tejas aircraft for the project. “In order to gain the trust of domestic and international buyers, HAL needs to increase its focus on quality control and manufacturing hygiene," says Banik. “It needs to iron out all the design and manufacturing flaws in its products by investigating and analysing all the past mishaps involving them."

Despite the massive orders, production continues to be a cause of concern. For instance, HAL can currently manufacture about eight Tejas aircraft a year, even though the company wants to ramp it up to 16 from next year. For now, it has ramped up its manufacturing facility with two additional units. “16 aircraft per year is a peak which we will have to deliver from next year," Ananthakrishnan says.

That could pose a challenge in timelines for the defence forces who are looking to ramp up on their fleet and squadrons, especially since the government wants to promote more domestic aircraft purchase. The last time the Indian government made a significant foreign purchase was in the case of 36 Rafale aircrafts. “If not for the Make in India program, the Cheetah and Chetak replacements could have gone to some foreign sources, and the same would have happened with the light combat helicopters," Ananthakrishnan says.

But, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the defence forces will line up to purchase anything that HAL manufactures. “Only when all their requirements are completely met and fulfilled and they have flown them, will they buy them," Ananthakrishnan says. At the same time, the increased focus on Make in India has also led to clear visibility in revenues for HAL, which Ananthakrishnan says allows the company to take the capital risks that it had long shied away from. “There is a very clear visibility, that in the future these orders are going to come to HAL," Ananthakrishnan says. “We can now start investing our money into expanding our capacity, and into design and development."

The company currently has an order backlog of Rs81,785 crore as of FY23 end. “Among all the defence stocks under our coverage, HAL has the most formidable order funnel with FY23 order book at Rs81,700 crore and a robust order inflow expected in FY24 (manufacturing orders worth Rs48,000 crore spares orders worth Rs17,000 crore)," brokerage firm ICICI Securities said in a report on May 18. “Potential orders for which AoN (acceptance of necessity) has been issued is at Rs36,000 crore and for which AoN has not been issued at Rs 65,000 crore." AoN essentially is usually the first step toward procurement and means that the government recognises the need for an equipment.

“Today we are sitting on an order book of almost Rs84,000 crore with another, Rs48,000 crore of orders in the pipeline and with a further visibility of Rs60,000 crore," Ananthakrishnan says. “When there is visibility, when the product is going to be acceptable, whether we are getting the orders or not, we will start manufacturing it. Because we know for sure that if not today, tomorrow the order is going to come. So that is where there is a paradigm shift in the approach of the company."

That has also meant a focus on newer areas of warfare including unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV). Two years back, the company launched a program, CATS (Combat air teaming system), a combination of both manned and unmanned aircraft. “Very few countries in the world have this type of program under development," says Ananthakrishnan.

All that means, even though the company has faced setbacks recently, it is gearing up for more exports. “We are now trying to pursue exports aggressively," Ananthakrishnan says. “We have got a range of indigenous products which we can offer to the customers. There is also a thrust from the government that a substantial portion of revenue should also be generated from the export."

“LCA Tejas is a potent platform with good safety records and is ideal for various export markets," says Banik. “However, HAL needs to re-gain trust among international buyers by displaying the operational successes of its capable platforms and ironing out the issues involving the problematic ones."

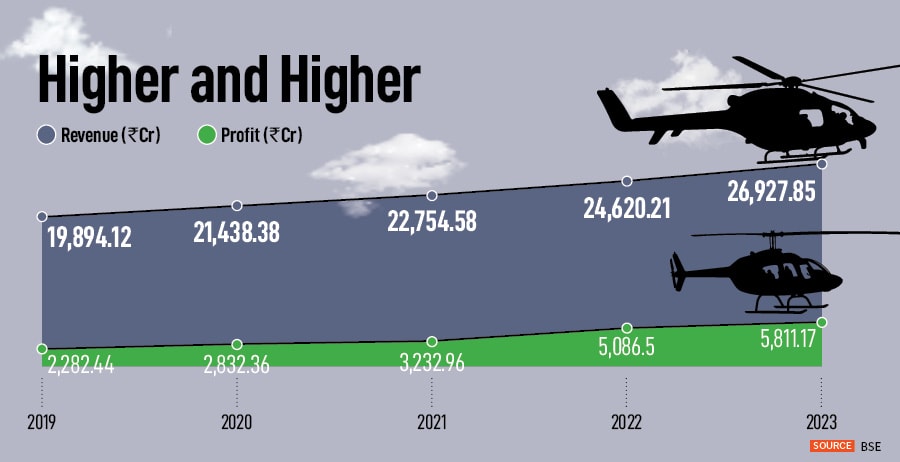

So where does HAL go from here? “Our growth has been very consistent, but not the growth the industry would expect. We are trying to see that our growth reaches double-digit numbers." In the process, Ananthakrishnan, who also functions as the CFO of the company is looking to bring down the company’s manpower costs, and make the organisation lean, accounting for only 14 percent of the cost from about 18 percent currently.

“HAL is the only company today which has got multiple platforms, multiple range of engines, and multiple avionics," Ananthakrishnan says. “We have got the capabilities which have been developed over 70-80 years. But I can only say there is enough space for everyone, even if some private industry is going to take it. We will not be falling short of any order because the programs are so huge."

First Published: Jun 12, 2023, 10:33

Subscribe Now