Flat is the new up: A fight for survival, and an opportunity ahead, for Indian s

Cheap money is done, and profits are sexy again, but it's still a great time to start up in India, investors say

There were 14 Indian unicorns anointed in the first three months of 2022. And then none in April, and May managed to throw up one, according to the unicorn tracker by Venture Intelligence, a data insights company that tracks the Indian startup ecosystem.

On May 12, Masayoshi Son, CEO of Japan’s SoftBank Group, one of the biggest investors in India’s startup ecosystem, said the strategy ahead would be one of “defence", after the world’s biggest tech investor—that has backed several Indian unicorns—reported record losses at its Vision Funds in the first three months this year.

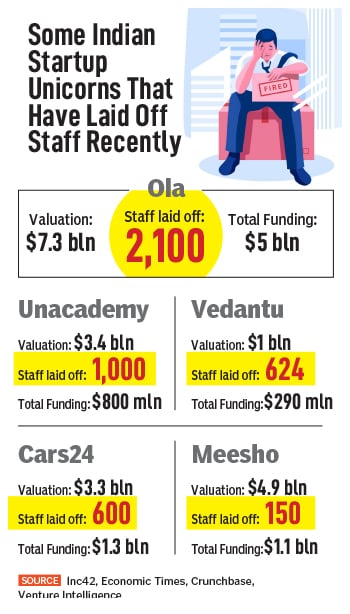

Inc42, an Indian startup news and analysis site, collected its own and other media reports to show that close to 8,400 people have already been laid off in the last three to four months by Indian startups, including five unicorns, by the end of May.

“Flat is the new up, and down is the new flat," says Mohanjit Jolly, a partner at the PE and VC firm Iron Pillar, recalling one of his favourite phrases during downturns. Startups that were expecting an uptick in valuation will now be okay with raising money at existing valuations, and some will also find themselves accepting lower valuations to ensure their funding goes through.

“There will be turbulence ahead," he says.

It won’t be uncommon for instances where term sheets are pulled or renegotiated, and even valuations renegotiated during closing documentation. “Late-stage companies that were expecting to raise hundreds of millions in follow-on financing are struggling in many cases to raise capital at any valuation," he says.

A combination of unabated global geopolitical conflict, worries about a recession in the US, the world’s biggest economy and tech market, and tightening money policies as central bankers around the world move to curb rising inflation, has made investors jittery, reflected, for instance, in the 25.3 percent fall so far this year in the Nasdaq-100 Technology Index.

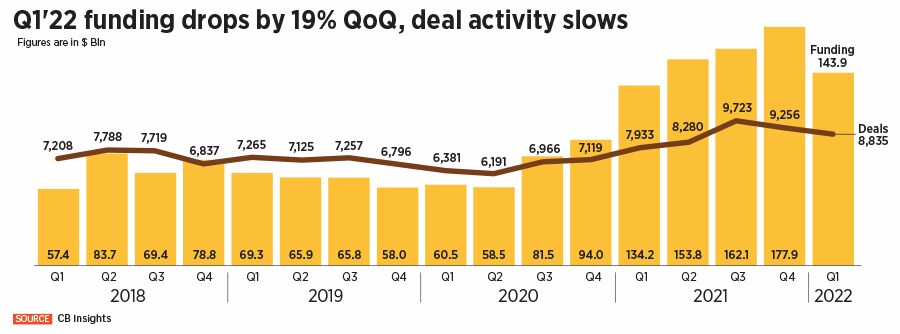

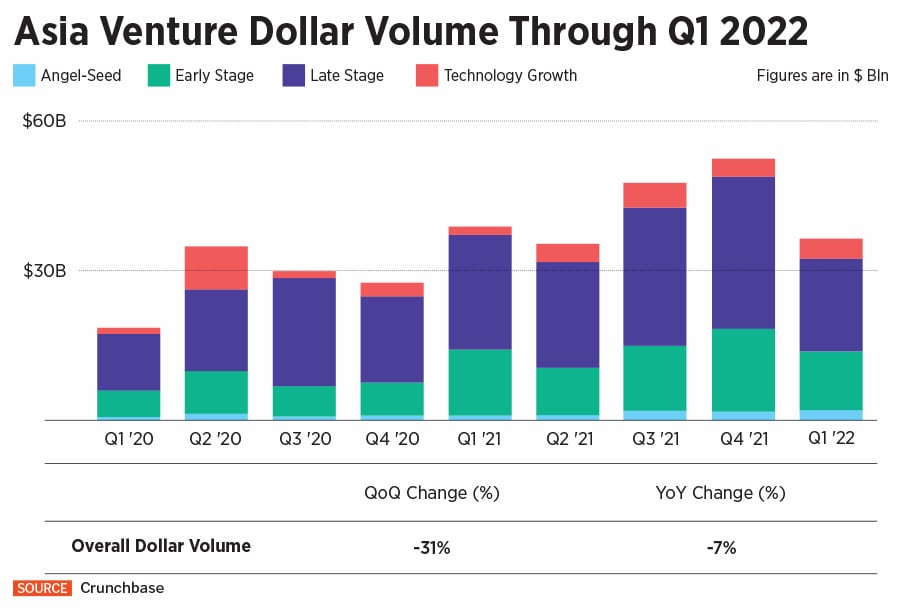

Calendar year 2022’s first-quarter venture capital funding worldwide, while still being strong, was lower by 19 percent sequentially, from the December quarter, research company CB Insights notes in its April 7 ‘State of Venture’ report. Funding in Asia, fell 31 percent for the first three months of 2022, compared with the Oct-Dec quarter of 2021, according to Crunchbase.

Calendar year 2022’s first-quarter venture capital funding worldwide, while still being strong, was lower by 19 percent sequentially, from the December quarter, research company CB Insights notes in its April 7 ‘State of Venture’ report. Funding in Asia, fell 31 percent for the first three months of 2022, compared with the Oct-Dec quarter of 2021, according to Crunchbase.

In India, private equity and venture capital funding was 27 percent lower in April 2022, compared with the same period last year, according to accounting firm EY and Indian PE and VC Association (IVCA). For India’s gradually maturing startup ecosystem, a timely reckoning is underway. Investors and founders alike are expecting the going to get tougher in the days to come.

“There will be a recalibration of valuations, and that adjustment has already started," Jolly says. In cycles like this, there is usually a three to nine-month lag between public market dips and the private markets fully internalising the reality of the downturn, he adds.

Venture capital firms, Jolly further says, will look to bucket their portfolio companies into three main categories, especially during crises: Those that have enough money for 18-24 months or more (stable), those who have only enough for the next few months but need additional capital either externally or internally in the next 6-12 months (‘metastable’) and those with immediate need or in the middle of a fundraise with little to no prospect of capital (unstable), “which may require triaging".

Funding will be tough across stages, not just for late stages, says entrepreneur and investor Raghunandan G, founder of the fintech startup Zolve, and co-founder of ride-hailing service provider TaxiForSure.

The reason for this is that one can expect a cascade effect of VCs at every stage conserving their cash to invest in the best of their existing portfolio companies via bridge rounds and so on, and therefore will have less money for new investments.

Typically, a VC firm will invest in about 20-25 companies with each fund, of which say two will do very well and another 5-6 companies will show promise and the rest will either scrape through or fail, Raghunandan says. Typically, during a downturn, VC firms will want to safeguard the 5-6 promising companies with the bulk of their capital.

And it’s in the interest of both the investor and the entrepreneur, he says, because, if a ‘down round’ happens, a VC firm stands to get more equity in a company for the same amount of money. And for the startup, in the face of the alternative that it could shut down, if a down round helps it to survive a tough stretch, then it is the better option.

"At Iron Pillar, we"re in a very fortunate position where pretty much our entire portfolio has either recently raised a very sizeable round or are in a position where they will be closing a fairly sizeable round," Jolly says.

"They"re sitting on significant capital where burn and runway is not an issue … so we"re not in a position where we have to do any portfolio triaging."

That said, all investors will now be advising companies to conserve cash, cut any flab, focus on unit economics and so on. Among the world’s most famous VC firms, Sequoia and Y Combinator, for example, have already circulated presentations and memos to founders on the way through this downturn.

The downturn will also reduce the number of me-too companies that are playing a thin or negative-gross-margin game with discounts and growth-at-any-cost mindset, Jolly says.

Iron Pillar has been conservative in entering companies at valuations vis-a-vis exit expectations. "We do not base the exit of our investments on a massive multiple. So we have always been very conservative where, the markets may be 25, 30x plus in terms of revenue or ARR multiples, but in terms of our own scenario building, we assume far more reasonable metrics"

“One thing I’ve seen in the market, and personally don’t like, is that some companies raising massive rounds were given valuations that they were expected to ‘grow into’ over the next 12-24 months," Jolly says. Now that there’s a significant downward re-calibration, these companies that were expected to grow will struggle to hit those numbers.

“One thing I’ve seen in the market, and personally don’t like, is that some companies raising massive rounds were given valuations that they were expected to ‘grow into’ over the next 12-24 months," Jolly says. Now that there’s a significant downward re-calibration, these companies that were expected to grow will struggle to hit those numbers.

For example, say SaaS company valuations are lower by 50 percent (from the height of the funding frenzy in 2021), which means if the ARR (annual recurring revenue) is one important metric for valuations to be based on, a company will have to double its ARR to stay at the valuation that was arrived at before the re-calibration happened.

“Survival is a pre-requisite to be able to thrive", and many companies are, or will soon be in survival mode. They will still try to raise money, but cost-cutting is a given, including difficult decisions such as layoffs.

The very high salaries at which engineers were hired will be much more rare, and ‘island hopping,’ where employees jump from one startup to another for increments every 6-12 months, will come down. As with any downturn, there will be a shakeout—including an uptick in mergers and acquisitions—many pushed by investors as well.

“I’ve recently had two inbound calls from VCs asking if I’m interested in acquiring companies that they didn’t want to invest in anymore," the founder of a successful, and profitable, SaaS company, tells Forbes India. “In the past, when I looked at fundraising, they would ask me ‘why are you profitable’. Now profitability has become important in their memos."

Startups that have a strong cash balance will get opportunities to buy competitors and others, to expand market share, gain intellectual property and add talented people.

An interesting aspect of this latest downturn is that it’s come just as several well-known VC firms raised large India-focussed funds. April 2022 recorded total fundraise of $1.5 billion across 16 funds compared with $569 million raised in April 2021 by eight funds, according to EY and IVCA.

The largest fundraise in April 2022 was by Elevation Capital that raised its eighth India dedicated fund at $670 million, which is its largest ever corpus.

Therefore, the money is there—in fact, a large amount of ‘dry powder’, as VCs often like to call cash reserves. The question is, who will likely get it. “There are two kinds of startups—those that got into the 2021 funding frenzy and those who were not influenced by it, and maybe didn’t even raise VC funding, stuck to the basics, and no one heard about them," says Raghunandan.

“This second category of companies is what we will start hearing about in 2022—that’s what happened in 2016 as well," he says.

Among those who raised funding at crazy valuations, again, there are two kinds of entrepreneurs, he says. “One set that allowed the money to not only go into their bank accounts but also into their heads." They changed their lifestyles, moved from modest Android phones to a high-end iPhones, gave all staffers fancy laptops and so on.

The other category is of those founders who took the money but didn’t alter their spending significantly. “They will do phenomenally well. We will also see a lot of consolidation … majority of them might be orchestrated by the investors themselves," he says. “It’s a phenomenal opportunity for some startups, but pain for the bulk of them."

During the peak time, if, say, 100 VCs chase 70 companies, one will now see, say, 30 VCs chasing 10 companies. “For good companies, there will always be capital, but the crazy valuations won’t happen and the FOMO will not be there, and there will also be co-investments, so everyone can hedge their bets," he says.

“At Zolve, we’re well capitalised with our seed round of $15 million and series A of $40 million, so we are sitting on a whole lot of cash," Raghunandan says. “We’ve burnt about $7-8 million, and with our current run rate, we can possibly last 3-4 years. We got lucky that way."

“Our burn will increase only if our growth increases significantly, but if our growth increases significantly, we should be able to raise capital (even in the current scenario), because it’s not that there’s no capital."

“And no down cycle will last 3-4 years, and if that happens there will be bigger problems than worrying about a company," he says.

“Good companies will rarely die of starvation. They can die of indigestion, but rarely of starvation, and the right investors will find them," says Sanjay Swamy, a founding partner at Prime Venture Partners, an early-stage VC firm in Bengaluru that has itself recently closed its largest India-focussed fund—Fund 4 at $120 million.

As long as there are entrepreneurs passionate about solving large enough problems, and willing to go the long haul, “we are always happy to talk to them and work with them", he says.

The downturn is likely to affect different sectors differently. For example, some software-as-a-service companies are expected to do better, being mostly focussed on customers in the US and Europe.

On the other hand, even without the downturn, India-facing consumer startups have already had a tough market. Their revenues are in rupees, but the costs were in dollars, Raghunandan says, because they had to pay their engineers at levels that would match what counterparts in the US would be paid.

“That’s the biggest reason why the best consumer startups you can think of in India today aren’t anywhere close to profitability," he says.

At Zolve, which helps people who have newly moved to the US, for example, get a local bank account, a credit card and other services, “we started investing in a lot of referrals, so we were able to arrest attrition", he says.

Now the market will see quite a few layoffs, which means there will be much more supply than demand, and there will also be a moderation of compensation as well.

“I’ve always maintained that the Indian customer is not cost-conscious but value-conscious," Swamy says. And companies flush with funds—sometimes faced with a land grab situation —rewarded consumers without adequately articulating the value of their products or services, he says.

Today, “when they are forced to conserve cash, they will be forced to focus on business viability and delivering value and customers will pay fair value", he says. For example, “is 10-minute grocery delivery really necessary, just because we can do it, will the customer pay for that or is 20 minutes the right model, which makes the business much more viable, I think all that will get thrashed out right now."

Six months from now, several of these companies that would have assumed they would have had the capital to bludgeon their way into the market, will now be forced to focus on viability and building proper business models here. “I think everybody will win in this."

Further, “India itself is really booming. Our fundamentals are strong, the opportunities are amazing," Swamy says. “This is a conversation we have every seven years, but what’s different between seven years ago and now is that the Indian opportunity is mind-blowing."

More people continue to tap the internet, smartphone penetration is still expanding, digitalisation continues to grow, due to both government support—with the combination of Aadhaar, UPI, India Stack, and the recent Health Stack—and private investments. And startup segments such as the SaaS companies are increasingly targeting global markets, Swamy points out.

A few other factors are also quite different today. For example, there is a new generation of entrepreneurs who have much more experience in putting together tech and business operations at scale, who have come out of the first generation of startups such as Flipkart, Zomato and others. The big drop off in mid-level experience that used to be there has now substantially been filled.

And even social acceptance is catching up, with a career as an entrepreneur or as an employee in a startup is now increasingly seen as a “first-class citizen of a career", he says.

“We have not seen any slowdown in terms of the opportunities," Swamy says. “I’m old enough to remember the recession of 1992 when I was job hunting for the first time, the 2001 dotcom bust, and in 2008, when I was a CEO raising funding at that time, it was a very difficult time. And then we’ve seen 2015-16 and 2020."

The closest analogy seems to be what happened in 2001, and conservatively people are expecting this cycle to last 12-24 months, he says.

“This is a bit of a reaction to what has happened in the global economy that is hurting us, but I don’t think fundamentally India is any less attractive than it was say six weeks ago," says Swamy. “Once investors calm their nerves about what’s happened in the US and start looking at India again, I think it’s going to look just as attractive again, so I think we will see India come roaring back in the entrepreneurial space."

First Published: May 30, 2022, 15:43

Subscribe Now