This entrepreneur wants India to make its own lithium-ion cells for electric veh

Rajat Verma already recovers raw materials from used cells at his venture, Lohum Cleantech. He wants to close the loop by making cells in India as well

Image: Amit Verma Illustrations: Sameer Pawar

Image: Amit Verma Illustrations: Sameer Pawar

Most countries don’t make their own lithium-ion cells for the batteries that power their electric vehicles (EVs) or energy storage systems. They import the cells from China, mostly, but also Korea and Japan and then assemble those cells into battery packs for various applications.

In India, even the battery packs are imported if one looks at applications like cars, other four wheelers and buses, although, of course, there are very few of these in the country. In case of two-wheelers or three-wheelers, however, a fair amount of local assembly of battery packs happens. And there are various companies doing this.

Rajat Verma’s Lohum Cleantech in Delhi stands out in two respects. One, in addition to making ‘first life’ or new batteries, the entrepreneur is also building a strong line of business out of ‘second life’ batteries — separating out the still viable cells from used batteries and repurposing them into batteries for suitable lower power applications. And two, he runs perhaps the only enterprise in the country that is involved in commercial extraction of the raw materials from the cells.

For now, Lohum extracts lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese (from the cathode of the cell), and graphite (anode) and ships them to the commodities market. “Our hope is, in a couple of years, either we or one of our partners will actually provide a complete closed-loop solution,” Verma tells Forbes India in an interview. That means, the raw material recovered would go back into a cell manufacturing process, new cells would be made and put back into new battery packs — all within India.

Thus far, one of the reasons that companies in the electric vehicle sector in India have focused only on battery assembly and not cell manufacturing is that China is sitting on massive cell-making capacity that it supplies to the world. Competing with it is tough. Currently, China has about 250 GWh (gigawatt hours) of annual capacity, which is about three-quarters of the global capacity. And China has plans to raise its capacity to nearly two terawatt hours by 2025-26, Verma says.

China dominated Bloomberg New Energy Finance’s (BNEF) lithium-ion battery supply chain ranking in 2020, having quickly surpassed Japan and Korea that were leaders for much of the previous decade, the research service said in a press release in September 2020. China’s success results from its large domestic battery demand, at 72GWh, and control of 80 percent of the world’s raw material refining, 77 percent of the world’s cell capacity and 60 percent of the world’s component manufacturing, according to data from BNEF.

Strategic Metal

The reason it is important to make cells in India is also that the metals that go into them, such as lithium, are geo-strategic commodities, Verma says, and India’s known reserves, including a new find in south India, are very small. India imported about $1.2 billion of lithium-ion batteries in the fiscal year that ended March 31, 2019 — tripling from the previous fiscal year — and an additional $929 million in the subsequent eight months, Economic Times reported in February this year, citing Harsh Vardhan, union minister for science and technology.

An ecosystem that relies entirely on imports of cells will be costlier to build and sustain in the long run, compared with one that can recover a substantial portion of the raw materials and make its own cells. And as the world moves to electric vehicles, without its own cells, India would merely go from being dependent on imports of fossil fuels to imports of lithium-ion cells.

India has an advantage on the labour front, Verma says, and an Indian plant with annual capacity of a one gigawatt hours’ worth of cells can be competitive with a Chinese factory with ten times that capacity, Verma says. “So in an ideal world, we would close the loop. No one has done that anywhere in the world and we do hope that we can be among the first to get there,” he says.

Two months ago, Verma raised $7 million in fresh funds in an investment led by Baring Private Equity Partners. The immediate use of the money is to more than double Lohum’s capacity to 700 megawatt hours, build a stronger team, and bolster ongoing efforts at the venture to build an extensive knowledge base on the entire battery lifecycle.

Lohum currently has an installed capacity of 300 megawatt hours per annum, which is roughly split half and half between new packs and recycled ones. For comparison, one megawatt hour worth of batteries can power approximately 500 two wheelers. Verma also wants to expand the company’s service network.

Today it is present in about a hundred cities, but Verma wants to be present “everywhere, deeper, stronger.” The network manages two different activities for the company. It services the batteries sold by Lohum and also collects back used ones. As Lohum builds partnerships with more OEMs (original equipment manufacturers, such as auto companies) it will need to be present in every city that they are present in—for both two wheelers and the three wheelers.

Lohum also provides batteries for stationary energy storage systems, for applications in the telecom sector, for example. The company makes batteries ranging from low-voltage applications to “1000 volt plus solutions.” The company also offers its own battery management system, communication systems, thermal management system, and vibration management system.

Second Life and Beyond

With the ‘second life’ or used batteries, Verma says very few around the world are trying to understand what is happening at the individual cell level. In most cases, people just gauge the available capacity and put the batteries back in the market, whereas at Lohum, used batteries are disassembled, good cells separated out and put back into use, and bad or ‘dead’ ones earmarked for raw material extraction.

“We have developed extensive heuristics and an extensive database around how to understand what will be the remaining life in a cell. And that is one of the core strengths of the company. Ultimately, we analyse everything at the cell level,” Verma says. With a state-of-the-art research and development lab, Lohum is continuously improving its ability to predict what can be done with any given cell.

“And that allows us to create a much differentiated play in the market, not just within India, but globally.” Lohum has collected more than 1.5 million miles of second life mobility data — including through IoT devices — and no one has done something like that anywhere in the entire global EV ecosystem, he claims.

By revenue contribution, battery sales account for the biggest chunk, while the material extraction operation brings in about a tenth of Lohum’s business. The venture has made rapid strides in improving the productivity of the extraction business. With over 2,000 iterations of tweaking the process, the machinery used and so on, yield has gone from 60 percent to 90 percent over the last three years or so. “I want to get to 97-99 percent,” Verma says.

The purity of the metals and the carbon extracted is also high, now, he explains, with cobalt sulphate at 99.9 percent and graphite at 99.5 percent. The ‘hydro-metallurgical’ processes involved are well known, but the complexity becomes higher when there is a mix of raw materials as in the case of the lithium-ion cells. Further, Verma is trying to perfect the balance between yield and purity while extracting the materials at room temperature or a bit higher — to keep costs low, in comparison with extraction methods that involve very high temperatures.

“How do you take all of them out with the highest yield, with the lowest operating expenditure, without polluting the environment? That"s the problem that we are trying to solve here,” Verma says.

Investing in Lohum, “we had a very strong thesis that over the next 10-15 years, EVs would take some of the share out of the IC engine market”, Arul Mehra, partner at Baring Private Equity, tells Forbes India in an interview. The technology is getting better and the cost of batteries continues to fall.

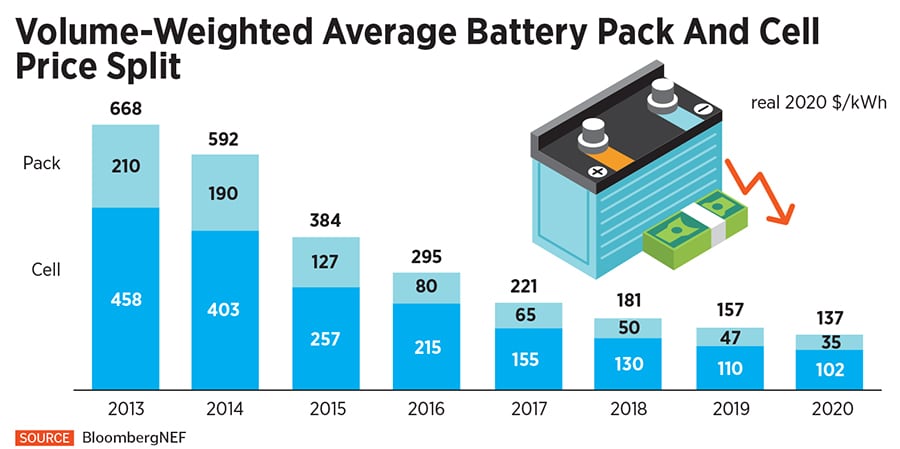

Lithium-ion battery pack prices, which were above $1,100 per kilowatt-hour in 2010, have fallen 89 percent in real terms to $137/kWh in 2020, BNEF said in a release in December last. By 2023, average prices will be close to $100/kWh, the research service projects. Costs are already hitting $100 per kWh at the cell level, but building battery packs takes the price higher by about a fifth.

BNEF’s 2020 Battery Price Survey, which considers passenger EVs, e-buses, commercial EVs and stationary storage, predicts that by 2023 average pack prices will be $101/kWh. It is at around this price point that auto makers should be able to produce and sell mass market EVs at the same price (and with the same margin) as comparable internal combustion vehicles in some markets. This assumes no subsidies are available, but actual pricing strategies will vary by auto maker and geography, BNEF said in its release.

Volkswagen, one of the largest auto makers in the world, for example, plans to spend $29 billion in building six battery factories, and charging stations worldwide. The German car company aims to sell a million EVs this year itself.

The $206 Billion Opportunity

In India, EV adoption will be led by two-wheelers and three wheelers. By 2030, India’s EV market could be between $28 billion and $51 billion in annual revenue terms, said a December 2020 forecast by Delhi-based think tank Council on Energy, Environment and Water, at its Centre for Energy Finance. Between now and then, India will need investments of $177 billion from OEMs (original equipment makers such as car companies) in vehicle production, $2.9 billion for the deployment of charging infrastructure and $12.3 billion in battery manufacturing, the research organisation estimates.

Competition will rise, just as it did in telecom, DTH or ecommerce, Baring’s Mehra anticipates. And Baring’s bet on Lohum hinges not just on Verma’s ambition to close the loop on battery production, but the venture’s overall global prospects. Mehra points out that Lohum’s extraction technologies will find interest overseas too in markets including the US, Europe and Australia.

“He has got a very large market size, a differentiated product that makes money, and he’s been accepted by a large number of OEMs, so there is no product risk so to say,” Mehra adds. “He is a really good founder, who understands technology, understands business and manages people well."

Verma doesn’t name customers, citing non-disclosure agreements, but says Lohum is a supplier to both leading two-wheeler makers — both low-speed and high-speed — and the larger makers of e-rickshaws and the L5 (large auto) segment. Lohum also supplies batteries to the telecom sector with customers among systems integrators and power companies. The venture is also running pilots with some of the large solar power companies in the country.

Two companies that have announced the intention of setting up cell manufacturing in India are also collaborating with Lohum to test the performance of the chemicals it extracts from the cells. Lohum has an annualised revenue run rate of more than $8 million and aims to hit $90 million in three years, it said in a press release in January, when it announced the funding led by Baring.

Lohum already has some operations in the US in Washington DC and Los Angeles and it is working with OEMs for battery pack and recycling solutions. The venture expects to set up its first recycling plant in the US by 2022. “We see a very unique opportunity because the entire world is shifting to battery power at the same time in two of the largest global industries — mobility and energy,” Justin Lemmon, co-founder and head of international operations, said in Lohum’s January funding press release. “These industries will look vastly different in 10 years and we want our solutions to play a significant role in that transition.”

In India, because of the Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid and) Electric Vehicles (FAME subsidy plan, now in phase II), auto makers are especially trying to localise batteries for the three wheelers. Today, about 70 percent of the batteries for the two-wheeler and the three-wheeler categories are being made in India. As one looks at cars, other four wheelers and buses, however, almost all the batteries needed are imports, Verma says.

In these cases, the volumes are relatively low, expertise is being slowly developed locally but the technology is in its nascency within India. For example, with these more advanced batteries, one needs state-of-the-art thermal management and cooling systems. “We are certainly developing the engineering capacity, but it’s still early days in my opinion.”

Verma is an engineer by training. He went to IIT Kanpur and then to Stanford University. He worked briefly in the space industry in the US, designing heat shields for re-entry vehicles, but turned to software at a startup called Kintana, where he was the technical lead. The startup was acquired by a company called Mercury Interactive, which in turn was bought by Hewlett Packard. Verma went back to school, to Harvard University this time, and earned an MBA.

He came back to India and worked in private equity for a bit, but always saw himself as an entrepreneur. He was studying the Indian market, and electronic waste looked interesting. It was “thoroughly unorganised, brutally competitive, extremely fragmented”, and he felt technology could make a difference. He acted as an advisor to a couple of companies on managing electronic waste and started studying what kinds of capabilities could be built in India in this area.

This eventually led to his spotting lithium-ion batteries as an opportunity that would become more mainstream. Verma wanted to look at it in a ‘holistic’ manner, and started Lohum in 2017. He has factories in Noida.

One obstacle in the way of faster growth of India’s EV ecosystem is money. While investors like Baring Private Equity and a few other venture capital firms have taken an early interest, and more are looking to jump in, banks are still holding back, Verma says. “Banks still have not understood what an electric vehicle is all about. I think they"re still struggling with that concept.”

As ventures such as Lohum acquire more data, it will make a dent in the costs involved in making batteries and related systems, which typically make up 30-50 percent of the cost of an electric vehicle.

Second, as in many other industries, more engineering talent is needed. “Today, when I look at the EV ecosystem reminds me of how the software ecosystem was back in ‘98, ‘99 — you know, two or three guys coming out of good engineering school, pursuing an EV of their own,” Verma says. The good news is, the EV ecosystem globally is playing out very well with an increase in both entrepreneurial ventures and investor interest. India will follow suit very quickly, he adds.

One thing that will also help is if the government takes a longer-term view on its policies and extends plans like FAME II to at least 2025, if not beyond. And it could accelerate the adoption of policies — currently in draft stage — on recycling to provide incentives to recyclers, he says.

The entry of billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk’s electric car company Tesla into the Indian market will also help, taking the excitement over EVs to the next level, Verma believes. Tesla could be the large player India needs, to play the role of the anchor around which the entire ecosystem can develop. "I"m hopeful that Tesla will bring that to the table,” he says.

Today, Lohum imports the cells for its ‘first life’ batteries, and the repurposed batteries are made largely from cells taken out from the used batteries the company collects back. Of late, it has also started sourcing them from other markets. Verma believes India can become a dominant player in the recycling ecosystem worldwide. The technology is available within the country, there are people available to work in such factories, and there is strong demand for the batteries that can be made.

“If we can do this successfully, and we certainly see the government supporting this vision, then India will never be only dependent on imports for the raw material. That"s at least something that we are trying to push as part of our vision.”"‹

First Published: Mar 22, 2021, 15:04

Subscribe Now