US Volatility: Is India insulated?

As US debt surges, bond yields spike, and Moody's downgrades its credit rating, analysts explain the possible impact on India

As investors navigate uncertainties with spikes in US bond yields amid ballooning debt, India seems to be somewhat insulated, although not entirely immune to an impending crisis.

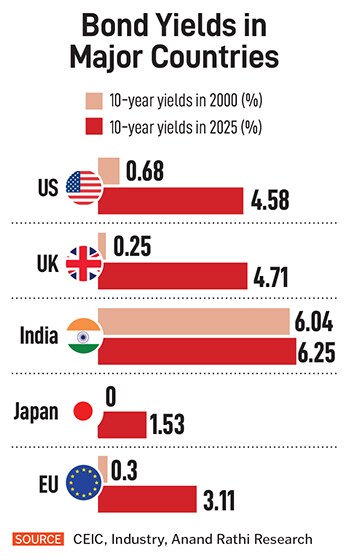

A worsening fiscal situation, growing public debt burdens, rising long-term borrowing costs and a rare credit rating downgrade of the US have heated its 10-year treasury yields to higher levels, of around 4.5 to 4.6 percent. In contrast, the 10-year bond yield in India is cooling off to around 6.22 to 6.25 percent, which has led to a narrow gap between US and India yields for the first time in 20 years. On May 19, this gap shrunk to about 173 basis points, a level last seen in 2004, shows Bloomberg data.

A rally in rupee benchmark 10-year bond (lower yield) has compressed yield spreads spurred by India’s favourable fiscal math, easing inflation, and a lower terminal repo rate, says Radhika Rao, senior economist, DBS Bank. This, she explains, is in contrast to fiscal concerns in the US, fanned by the passage of unfunded tax cuts.

The narrowing gap between Indian and US bond yields signals shifting global capital flows. Historically, India’s higher yields compensated for inflation and currency risks, but the compression suggests the presence of different macro environments in various economies. With US yields rising due to fiscal concerns, India may see some volatility, particularly in foreign portfolio investments (FPIs) in debt markets, says Abhishek Bisen, head-fixed income, Kotak Mutual Fund.

A shrinking yield differential could slow foreign institutional investor (FII) inflows and external commercial borrowing (ECB), potentially pressuring the rupee. “However, India’s improving macroeconomic fundamentals, easy monetary policy by the Reserve Bank of India [RBI] and fiscal discipline help mitigate major disruptions. Overall, while volatility is possible, India’s relative stability and strong investor confidence may limit adverse effects," Bisen adds.

“India is relatively insulated and better placed among major emerging markets [EMs] due to macroeconomic tailwinds, but one cannot rule out the impact through tightening of financial conditions," says Garima Kapoor, economist and EVP, Elara Securities. She adds that factors like visibility of low inflation, a deep rate cut cycle, focus on fiscal consolidation, comfortable forex reserves and a resolute focus on macro prudential stability places India apart from its peers. “Surge in yields can lead to mounting notional losses, leading investors to search for liquidity and hence book profits elsewhere across asset classes. A rapid surge in yields globally can also lead to tightening of financial conditions globally, including India."

However, in the current cycle, the impact on India is expected to be less damaging due to its business cycle. If an impact of the spike materialises, it will be short term as global pension and hedge funds start to book paper losses, Kapoor explains. There can be an impact on fund flows in India, especially debt, but it is likely to be subdued, she adds.

However, in the current cycle, the impact on India is expected to be less damaging due to its business cycle. If an impact of the spike materialises, it will be short term as global pension and hedge funds start to book paper losses, Kapoor explains. There can be an impact on fund flows in India, especially debt, but it is likely to be subdued, she adds.

In India, inflation is cooling off and is within RBI’s comfort zone. The consumer price index (CPI) inflation was at 3.2 percent in April. Headline inflation also eased in January and February 2025, driven by a sharp decline in food prices. The RBI projects CPI inflation to be 4 percent in 2025-26, with quarterly estimates at 3.6 percent in Q1, 3.9 percent in Q2, 3.8 percent in Q3, and 4.4 percent in Q4. It projects real GDP growth to be 6.5 percent for 2025-26, suggesting continued recovery momentum.

“This combination of high growth, receding inflation, and improving fiscal metrics positions India as a relative bright spot in a world grappling with fiscal strain and policy uncertainty," says Sujan Hajra, chief economist, Anand Rathi Financial Services.

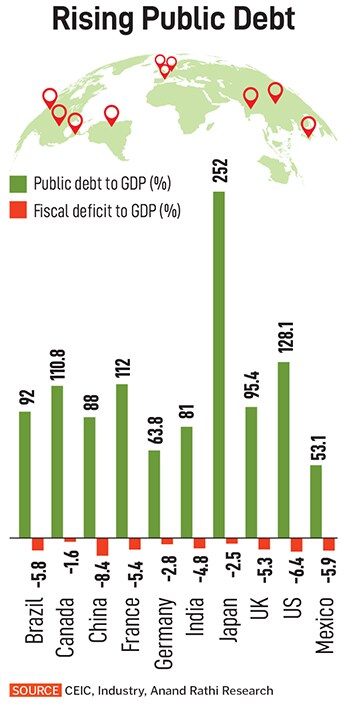

In contrast, widespread fiscal loosening has led to rising debt in advanced economies, but credit rating agencies have been selective in their response. Moody’s downgraded its sovereign credit rating of the US on concerns of its growing $36 trillion debt burden by one notch, but revised its outlook to ‘stable’ from ‘negative’. Moody’s had maintained the top-tier ‘Aaa’ rating of the US since 1919, and was the last of the three major credit rating agencies to downgrade it.

Moody’s said the fiscal proposals under discussion in US President Donald Trump’s administration are unlikely to deliver a sustained, multi-year reduction in deficits. It projects that federal debt will rise to about 134 percent of GDP by 2035, up from an estimated 98 percent in 2024.

However, for India with ‘Baa3’ rating and a ‘stable’ outlook, Moody’s thinks the economy is well positioned to deal with the negative effects of US tariffs and global trade disruptions due to its large domestic economy and low dependence on exports. “Government initiatives to boost private consumption, expand manufacturing capacity and increase infrastructure spending will help offset the weakening outlook for global demand. Easing inflation offers the potential for interest rate cuts to further support the economy, even as the banking sector’s liquidity facilitates lending," says Moody’s.

“Moody’s recent downgrade of US sovereign rating highlights debt concerns," says Bisen. He adds that the Federal Reserve’s relatively tight monetary stance and ongoing balance sheet reduction have restrained liquidity, while elevated deficits and tariff risks add to uncertainty. Bisen says that markets are focusing on local macroeconomic fundamentals, pricing risk accordingly in both equity and debt. “While US fiscal risks may drive global volatility, EMs including India could outperform due to a weaker USD and regional disinflation trends," he explains. Unless the US Federal Reserve adopts a more hawkish stance, such volatility could present a buying opportunity. India’s low current account deficit also helps limit currency pressures.

In the last five years, public debt and fiscal deficits increased sharply in most large countries. The fiscal expansion as a reaction to pandemic-led disruptions, followed by sluggish global growth and government support amid economic and geopolitical shocks, pushed debt-to-GDP ratios to new highs (see chart). In the US, public debt soared to over 128 percent of GDP by 2024, with projections for further increases.

“Fiscal deterioration and sustainability are growing concerns, especially in the US and it can have a negative impact on global growth," says Puneet Pal, head-fixed income, PGIM India Mutual Fund. He is, however, optimistic that India will not feel much of an impact. “India is well on track to achieve 6 to 6.5 percent GDP growth in fiscal year 2026."

Rao of DBS Bank is confident that the compression between rising bond yields in the US and cooling off in India is likely to stay, given a favourable change in India’s rates backdrop, while investors’ worries over US’ fiscal strains are still to be addressed. “Domestic demand for the rupee-denominated papers is strong, while foreign portfolio flow into debt is lower by over $4 billion fiscal year-to-date. Equity markets have witnessed net foreign inflows in the same period," she adds.

Rising benchmark yields in the US typically reflect concerns over fiscal stress, sticky inflation or a tighter monetary policy. Higher yields increase borrowing costs, raise the discount rate applied to future corporate earnings and provide a more attractive, low-risk alternative to equities, often resulting in pressure on US stock valuations and increased volatility. In contrast, falling bond yields in India are a sign of easing inflation, policy rate cuts and improving fiscal discipline. Lower yields not only reduce funding costs for Indian companies but also tend to boost investor risk appetite for equities over fixed income.

Rising benchmark yields in the US typically reflect concerns over fiscal stress, sticky inflation or a tighter monetary policy. Higher yields increase borrowing costs, raise the discount rate applied to future corporate earnings and provide a more attractive, low-risk alternative to equities, often resulting in pressure on US stock valuations and increased volatility. In contrast, falling bond yields in India are a sign of easing inflation, policy rate cuts and improving fiscal discipline. Lower yields not only reduce funding costs for Indian companies but also tend to boost investor risk appetite for equities over fixed income.

Though Pal anticipates further narrowing of yield differentials between India and the US, he says he would turn cautious if the yield differential narrows to less than 100 bps. “Indian yields still have room to move lower, and at present we do not see any significant impact of elevated yields in advanced economies or the US on Indian bond markets," he says. Pal warns there can be some negative impact if US yields crosses and remains above 5 percent, which can lead to FII outflows from Indian bond markets.

Others concur. According to Kapoor, the gap between the two benchmarks in India and the US may narrow further, but the pace is likely to slow down from here on. “A lot of the current macro conditions in India are priced in the yields. In the US we price in the Fed to step in at some point this calendar year, which can arrest the surge in yields. We see 200 bps gap by the end of 2025," she says.

Bisen agrees that further compression is possible if the current momentum holds, but the scope is limited: “However, India’s high yields help absorb volatility, keeping its debt market attractive. Other EMs like Brazil and Turkey may present compelling opportunities, though each comes with its own risks. If US policy makers resort to quantitative easing [QE] or yield curve control [YCC] to stabilise treasuries, the dollar may weaken. Until then, India’s currency could remain under mild pressure as rate differentials continue to narrow."

The yield differential suggests a reallocation of global capital, as risk-adjusted returns in US equities become less attractive and Indian financial conditions improve both foreign and domestic investors may increasingly favour Indian stocks, says Hajra. The result is a situation where the Indian equity market is poised to outperform its US counterpart. Despite the continued softening of bond yields since 2024, there has been no re-rating of Indian equities. “This suggests the possibility of the same in the next one year," he adds.

Benchmark government bond yields—such as the US 10-year treasury or India’s 10-year G-sec—play a pivotal role in shaping equity market trends. Rising bond yields signal higher borrowing costs and a more attractive alternative for investors seeking safe returns. This typically results in re-pricing of riskier assets like equities: Higher yields can lead to lower equity valuations, as the present value of future corporate earnings is discounted at a higher rate.

Moreover, rising yields often reflect expectations of a tighter monetary policy or concerns about inflation, both of which can squeeze corporate profit margins and dampen consumer demand. Sectors that rely heavily on debt or are sensitive to consumer spending—such as real estate, infrastructure, and discretionary goods—tend to be more adversely affected. Conversely, when benchmark yields fall, equities usually benefit.

Lower yields reduce the cost of capital for businesses and make fixed income investments less attractive compared to stocks, often driving more flows into equity markets. Growth-oriented sectors tend to outperform in such environments.

First Published: May 30, 2025, 14:25

Subscribe Now