Why climate adaptation in India is a VC opportunity: Five areas to focus on

The latest State of Climate Finance in India report by Climake argues comprehensively that the adaptation landscape is ready for private money

The lives lost and the ongoing devastation in Wayanad in Kerala—just the latest in climate change related disasters in the country—is one more stark reminder that action is needed, urgently.

Unsurprising then, that within the yawning gap between current private funding of climate action and what is actually needed, the focus on climate adaptation in India is further under-represented in policy, finance, and innovation. The latest annual report by Climake, an organization working to develop India’s private climate finance ecosystem, makes this point.

The report, The State of Climate Finance in India 2024, is out today.

The contrast is clear when it comes to investor interest in the segment, the report notes: Lifetime investments in all adaptation sectors add up to only $899 million, in India. Climate mitigation, on the other hand, received $4.7 billion in private investments in 2023 alone, according to Climake’s estimates.

Climake is a four-year-old organisation founded by Simmi Sareen and Shravan Shankar to help develop a private finance ecosystem in for climate action in India. As part of their work, Sareen and Shankar compile an annual report on climate finance in India.

“We need to talk about climate adaptation," the experts say, in the fourth edition of their report, in collaboration with the impact investment firm Unitus Capital, where Sareen is a director, in Mumbai.

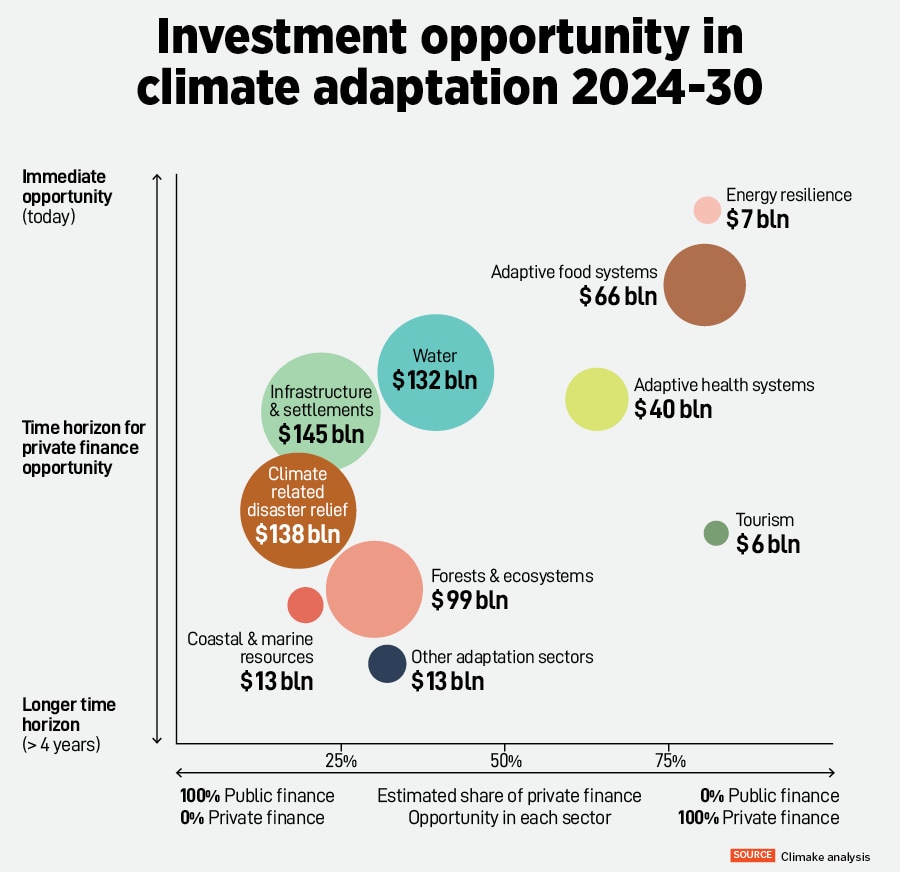

“Private sector capital has long believed that adaptation finance is public goods and not suited for commercial capital," they say. While this is true in areas such as disaster relief and support for climate migrants, “there is much that offers opportunity and needs focus from commercial ventures and funders."

A chartered accountant by training and a graduate of the Sloan Masters programme from London Business School, Sareen has worked in the field of finance for more than 25 years. Shankar, based in Chennai, plunged into sustainable development right out of college, with a degree in chemical engineering and environmental engineering from the University of Nottingham in Britain. He brings to Climake close to 15 years of experience studying climate tech and entrepreneurship.

Climake works with high potential startups in the field of climate change to help them access capital. The organisation works with funds directly to help them figure out what their investment thesis could be, and therefore what their focus should be.

“We also work on new types of financing instruments because this is a new sector. It"s very hardware-centric and asset heavy," Shankar tells Forbes India in an interview on August 6. “And we have built a whole network of incubators, funders, investors that we talk to on an ongoing basis to try and influence how climate finance should grow from here."

With the focus on climate adaptation in their latest report, Shankar and Sareen offer “a guide on adaptation for curious investors as they explore their first investments in this segment," they say.

If one looks at where climate finance is today, Climake estimates that in 2023 there was about $22.5 billion in private capital that came into the sector in India, Sareen says. Of that about $4.8 billion was equity investments and given the asset heavy nature of the sector, $17.7 billion comprised debt investments. What India needs, however, is $108 billion in climate finance every year through 2030, Sareen points out.

India was the 7th worst-hit country due to extreme weather resulting from climate change, in 2019, according to the latest available Global Climate Risk Index, which was compiled in 2021 by Germanwatch, an independent non-profit organization in Germany. They are expected to publish a new index this year, after missing 2022 and 2023 due to lack of data, according to their website.

Working on climate change has two aspects. Mitigation is about reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and this is where much of the VC (venture capital) and entrepreneurial activity has been, so far.

“For the longest time, the narrative has been that we"ll face the effects of climate change down the line. But that"s not true. We"re facing it today. What"s happening in Wayanad, what"s happening in Himachal and all the other places, it"s really extensive," Sareen says.

Therefore, not just climate mitigation, but adaptation too needs a lot more immediate attention, the co-founders of Climake say. Their report is an attempt to identify the areas that are most promising from a private investor’s point of view in climate adaptation. Further, Sareen and Shankar also offer a roadmap to investors wanting to look at adaptation.

The areas that Climake has identified as the most promising from a private investor’s perspective—meaning, where startups can actually go beyond prototypes, and become viable commercial businesses—are sustainable food systems, sustainable cooling, access to water, adaptive built infrastructure, and adaptation data, analytics, and finance.

Between now and through 2030, Climake estimates that some $200 billion in private investments are needed in just adaptation, in India. Of that, food and agriculture alone has the potential to absorb 25 percent, Sareen says.

One reason that climate adaptation investments are more viable today is that the science and technology has advanced, Sareen says. “Today, we can predict climate events as there are already models out there very scientifically proven."

Another cause for optimism is that “we have started to see a lot more interest from the investor side in investing in this or at least talking about adaptation," she adds. For now, not much actual investment is happening, but more private investors are interested in the topic and there are more conversations.

“Adaptation is hard, right? How do you measure the impact of investing in a company that"s making cooling easier? Or investing in a company that"s improving farm productivity?"

This is a lot more difficult to measure than, say, investing in a solar project and calculating the equivalent carbon reduction, she says.

Over the last 12 months, however, led by development funding institutions, which are often national or international agencies backed by the rich countries, interest and commitments to climate adaptation is rising. Large corporations are joining in, says Sareen, “because data shows that listed companies globally will lose at least $4 trillion in value, due to the impacts of climate change."

“Even if all the emissions become zero today, you will still have glacier melting, still have high temperatures. So, these companies need to figure out how to save themselves from that," she says. One way is to buy solutions, which is how startups in the area of climate adaptation have a more promising future today, versus five years ago.

One other observation that Sareen offers is that “there"s a lot of activity we see on what we think of as two ends of the spectrum. There is a lot of seed capital coming in." In fact, about 60 percent of the equity transactions, last year, were seed transactions. They were small transactions of Rs1-3 crore, and sometimes even smaller, seeding new ventures doing innovative work, getting into new sectors.

These investments are coming from a range of people, including angel investors, high-net-worth individuals, family offices, and hundreds of VC funds that are doing early-stage investing.

At the other end the spectrum are very large transactions. Recall that about $4.8 billion of equity investments came in last year. Of that about 70 percent was accounted for by just 20 transactions. These were large transactions in areas such as renewables, bioenergy in agriculture, and electric mobility, where the investors are typically InvITs (Infrastructure Investment Trusts), strategic investors, development finance institutions and so on.

Such organisations prefer to invest upwards of $100 million or more in individual transactions.

Therefore, there is a large “missing middle," Sareen points out, wherein “once you"ve got an emerging company which has accessed some initial form of capital, but then needs to get to a level of strong growth."

One way to bridge this gap could be to have the large institutions become limited partners in the various venture capital firms that are more equipped to make smaller ticket investments in the order of a few million dollars, for example.

For investors in this space in India, therefore, “there is pipeline (of startups) available, but you need a specific context to really be aware that this is what is really going to be the opportunity here," she says.

What is cause for optimism is that in 2023 alone Climake identified 120 new funds which were investing in climate for the first time. Overall, from the time they started tracking financing in this space four years ago, Sareen and Shankar have identified 475 VC firms that have invested in climate ventures in India. Half of them were active in 2023 as well.

There is a growing list of mainstream VCs such as Peak XV Partners, Accel, and even Tiger Global that are serious about climate tech investments in India. Among the smaller VCs, specialists such as Theia Ventures, deeptech focused firm Speciale Invest, Ankur Capital, and Spectrum Impact, which is a family office, are doing exemplary work.

They are investing in ventures in areas such as alternative materials, water filtration, industrial decarbonisation efficiency, “which nobody else is doing right now," Sareen says. “They"re seeding companies which are not mainstream investment today, but these will become big sectors if these companies succeed."

In climate tech investments in India, “structures need to be different, and especially so in the early-stage ecosystem," Shankar says. “We might have said that India does not have as much of a problem in innovation, but there"s a difference between developing a solution and making it commercial pilot ready."

“It"s a big problem. The traditional accelerator programmes are just not effective for this space. They"re too short term."

Two institutions that addressing this in India are US-based Third Derivative and Indus DC. The former describes themselves as an open collaborative climate ecosystem builder bringing together corporates, funders and startups. The latter is a venture studio specifically to help build deeptech startups in the area of climate change.

“We are at a critical inflection point as far as climate change is concerned. We are seeing the effects everywhere, right?" Sareen says. “But this is (also) potentially the most excited we have been since we started focusing on the sector on where we are in terms of solving for this."

First Published: Aug 07, 2024, 12:16

Subscribe Now