A resident of BDD Chawl in Mumbai’s Worli locality, she tried to take up other jobs to supplement her income, but either there were safety issues or the roles were not flexible enough for her to take them up along with domestic responsibilities. “It’s difficult to keep the house running,” says Thorat, whose parents passed away when she was a teenager, resulting in her quitting school to support herself and her three siblings.

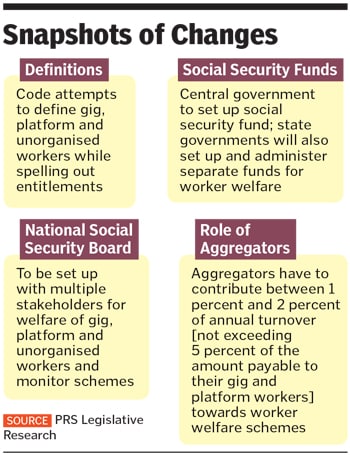

She is unaware that just a week before our conversation in early October, the Parliament passed three Codes in an attempt to overhaul the complex labour laws of the country. This includes the Code on Social Security, which, among other provisions, directs aggregators like ride-sharing services, food and grocery delivery services and ecommerce platforms, to contribute 1 to 2 percent of their total annual turnover towards social security provisions for workers. This includes disability and life insurance benefits, accident cover, maternity coverage, creche services, old-age protection, gratuity and provident fund contributions.

Priyanka, however, worries this might hit her income further. “If you start deducting even ₹200 or ₹500 from our monthly income for these benefits, it will be a problem. If I earn only about ₹10,000 a month and have a hand-to-mouth existence, I need every penny in hand to make ends meet.”

About 90 percent of gig workers lost their income since the Covid-19 lockdowns, according to an August survey by global fintech venture firm Flourish Ventures. Conducted among 770 ride-sharing drivers, delivery workers and house cleaners registered on digital platforms, it states that nine out of 10 gig workers with monthly income of ₹25,000 pre-pandemic were making less than ₹15,000 a month now. More than a third of gig workers were making about ₹168 per day or less. About 47 percent could not cover their expenses for a month without borrowing money, while 83 percent had to use up their savings to survive through the crisis.![ola and uber ola and uber]() While there is no reliable data on the number of jobs created by the gig sector, one gets an idea through Niti Aayog’s statement that Uber and Ola created over 2 million jobs from 2014 to 2019[br]According to Sharma, while provisions like provident fund and gratuity might be beneficial to workers in the long run, there might be opposition or pushback because it will hurt their immediate income. “Cab aggregators, foodtech or ecommerce platforms whose unit economics is still negative—and they are nowhere close to profitability—will definitely push the cost on to the gig workers,” he says. “These companies are struggling with high attrition rates, and this might make it more difficult for them to engage gig workers.”

While there is no reliable data on the number of jobs created by the gig sector, one gets an idea through Niti Aayog’s statement that Uber and Ola created over 2 million jobs from 2014 to 2019[br]According to Sharma, while provisions like provident fund and gratuity might be beneficial to workers in the long run, there might be opposition or pushback because it will hurt their immediate income. “Cab aggregators, foodtech or ecommerce platforms whose unit economics is still negative—and they are nowhere close to profitability—will definitely push the cost on to the gig workers,” he says. “These companies are struggling with high attrition rates, and this might make it more difficult for them to engage gig workers.”

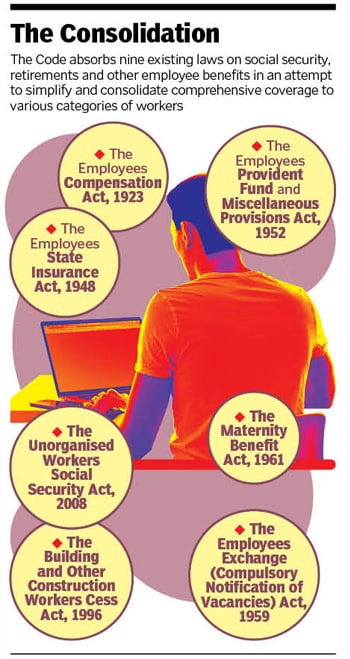

Implementation of the Code on Social Security would change how gig workers are hired and how their payouts are structured by organisations, says Pravin Agarwala, co-founder of BetterPlace, which connects blue-collar workers to companies. It works with Ola, Flipkart, Ecom Express, Swiggy, Zomato and Dunzo, among other organisations. “If I have to make a vague estimation, the costs for companies would go up by 10 to 15 percent. Some companies might pass on the cost to employees, while others might consider hiring these workers full-time since they anyway have to shoulder the security benefits.” He adds that the nuances will be clearer once the rules for implementation are framed.![consolidation consolidation]() Overlapping Definitions

Overlapping Definitions

While there is no reliable public record or data on the exact number of jobs created by the gig sector or the strength of the workforce, one gets an idea about the estimated size of this economy through government think-tank Niti Aayog’s statement that just between cab aggregators Uber and Ola, more than 2 million jobs were created between 2014 and 2019. The Global Gig-Economy Index 2019 published by US-based financial services firm Payoneer indicates that around 1.3 million people joined the gig economy in the second half of 2019, a 30 percent growth from the first half of the year. Trade association Assocham, in a January 2020 report, stated that India’s gig economy will have a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17 percent and will be valued at $455 billion by 2023.

In an attempt to streamline this economy, the Code on Social Security, for the first time, attempts to define who can be called a gig, platform or unorganised worker. A gig worker, it states, is someone “outside the traditional employer-employee relationship”, while a platform worker is someone who provides services through an online platform. An unorganised worker is someone who works in the unorganised sector, and is not already covered by the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, or other provisions like provident fund and gratuity. This includes home-based and self-employed workers. The Code does not include agricultural wage workers, domestic workers, street vendors or bidi workers.

There are, however, various overlaps in these definitions. A document by non-profit PRS Legislative Research dated September 2020 gives the following example: In the absence of appointment letters and regulation of work timings by the employer, a driver working for one app-based cab aggregator might work for its competitor as well, thus falling under the gig worker definition. However, he would also qualify as a platform worker since he pursues his job through an online platform. This driver might also be categorised as an unorganised worker because he is self-employed. “With such overlaps across definitions, it is unclear how schemes specific to these categories of workers will apply,” the document states.

![security code security code]()

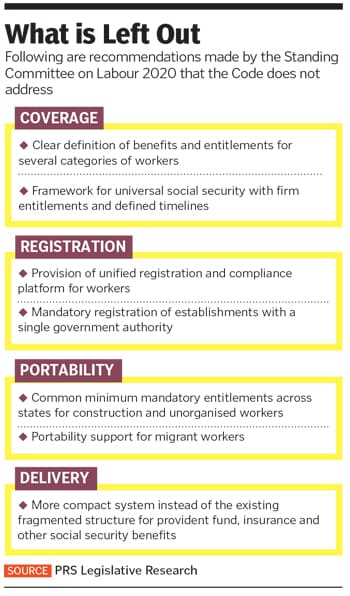

Rosa Abraham, research fellow at the Centre for Sustainable Employment at Azim Premji University (APU), points out that many recommendations made by the Standing Committee on Labour have not been addressed in the Code. The committee, for instance, had suggested expanding the definition of unorganised workers to include gig and platform workers and making the definition of gig workers more specific to avoid misinterpretation.

“As it stands now, there is neither a legal mandate nor universal coverage. There is no time frame or accountability on how these provisions should be met,” she says. “If you look at the language, it is just recommendations: ‘As may be specified’, ‘as may be formulated’ etc with respect to contributions and benefits.”

The labour ministry, on its part, said the language was a “conscious decision” of the government as it “provides for dynamism and flexibility to those provisions which are amenable to change as per needs of time, without undermining the powers of Parliament”. Union labour minister Santosh Gangwar said the Code on Social Security will be implemented by December, along with the Industrial Relations Code, the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code and the Wage Code.

Abraham believes the Code fails to be a step up from The Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act of 2008, which was the first of its kind to identify unorganised workers and then create a social security map for them. “But it collected these huge funds [through Budgetary allocations], that were left underutilised.” Annual CAG audit reports on the Union government for the years after this Act was announced indicate that only half or less than half of the budgetary allocations for social security benefits was actually spent.

“The Code is more like a political manifesto than a legal document. Most of it is vague and lofty promises without a roadmap to actualise them,” says Sanjoy Ghose, an advocate practising in Delhi. Agreeing with Abraham, he says many states had not implemented the 2008 Act over a decade after it came into force, rendering it largely ineffective.

Taking up one provision about the Central government setting up a fund for these workers and also calling for separate state-level funds, he says, “there is no clarity on how they will do it, what kind of money will be required, how those funds will be managed or processed, and who will be accountable”.![social security changes social security changes]() Pro-Business?

Pro-Business?

The Code provides thresholds on the size of establishments (such as minimum 10 or 20 employees) that will be eligible for social security coverage. Moreover, only employees earning above a certain amount [to be notified by the government] in these establishments can avail of benefits. “So workers in many companies with less than 10 employees will not be included,” says Agarwala. “But from a strategy point of view, it might make sense for the government to start with larger organisations and then go down to smaller numbers so that implementing the process would be easier.”

Labour economist KR Shyam Sundar, who is a professor at the Xavier Labour Relations Institute in Jamshedpur, says even though the Code talks about registration of gig, platform and unorganised workers, provisions for portable smart identification cards have been “carelessly omitted”.

To which Abraham of APU adds that the process of registration itself has had a poor track record under the 2008 Act. “Consider how the registration of construction workers is less than 10 percent,” she says, explaining that registration must be incentivised with at least a one-time money transfer for it to work. “Instead, the Code adds another layer of documentation by making Aadhaar mandatory.” Abraham also points out that ASHA and anganwadi workers, who have been at the frontline of the fight against the Covid-19 pandemic, have been kept out of the ambit of the Code.

Advocate Ghose believes the approach taken to draft the Code is pro-industry instead of pro-worker. “Look at how the penal provisions have been changed and diluted,” he says. For example, there is no stringent penalty for non-contribution of provident fund dues by the employer. In case of gratuity, the principal employer is not liable if the contractor through which these workers are hired does not pay them.

“First of all, industries or businessmen are hardly prosecuted for labour law violations. Second, the narrative behind some of these changes is that provisions are often misused by government inspectors to extract money from the companies. There might be truth to that, but the government should have focussed on plugging those issues without diluting penal provisions,” Ghose says, adding that the law also does not obligate the government to disseminate information and create awareness among workers about their entitlements, which is necessary for regulations to have the intended impact.

Economist Sundar agrees that “the government seems to be largely influenced by the employer’s lobby, which might affect the quantum of social security contributions that reach the workers”. Referring to the inadequacies of the Code, he says, “We analysts can only hope that when the rules are framed and opened for public consultation, these difficulties would be ironed out.”

Abraham says, “The Code is disappointing, so one hopes that when they frame the rules, some kind of tweaks are put in place. Because as it stands now, it is likely to eventually die the death of the 2008 Act.”

The Code directs digital aggregator platforms, like food delivery services, to contribute 1 to 2 percent of their annual turnover towards social security provisions for their workers[br]When the going gets tough, Priyanka Thorat wonders what it would be like to have a job with a steady income and other monetary benefits. The 24-year-old has been working as a delivery executive with foodtech platform Swiggy for the past three years, but things have been difficult of late. Earlier, she used to complete between 20 and 25 deliveries daily, but since the lockdown in March, barely 10 orders come her way every day. This has resulted in her weekly income reducing from approximately ₹4,000-₹5,000 earlier to ₹2,000-₹3,000.

The Code directs digital aggregator platforms, like food delivery services, to contribute 1 to 2 percent of their annual turnover towards social security provisions for their workers[br]When the going gets tough, Priyanka Thorat wonders what it would be like to have a job with a steady income and other monetary benefits. The 24-year-old has been working as a delivery executive with foodtech platform Swiggy for the past three years, but things have been difficult of late. Earlier, she used to complete between 20 and 25 deliveries daily, but since the lockdown in March, barely 10 orders come her way every day. This has resulted in her weekly income reducing from approximately ₹4,000-₹5,000 earlier to ₹2,000-₹3,000. While there is no reliable data on the number of jobs created by the gig sector, one gets an idea through Niti Aayog’s statement that Uber and Ola created over 2 million jobs from 2014 to 2019[br]According to Sharma, while provisions like provident fund and gratuity might be beneficial to workers in the long run, there might be opposition or pushback because it will hurt their immediate income. “Cab aggregators, foodtech or ecommerce platforms whose unit economics is still negative—and they are nowhere close to profitability—will definitely push the cost on to the gig workers,” he says. “These companies are struggling with high attrition rates, and this might make it more difficult for them to engage gig workers.”

While there is no reliable data on the number of jobs created by the gig sector, one gets an idea through Niti Aayog’s statement that Uber and Ola created over 2 million jobs from 2014 to 2019[br]According to Sharma, while provisions like provident fund and gratuity might be beneficial to workers in the long run, there might be opposition or pushback because it will hurt their immediate income. “Cab aggregators, foodtech or ecommerce platforms whose unit economics is still negative—and they are nowhere close to profitability—will definitely push the cost on to the gig workers,” he says. “These companies are struggling with high attrition rates, and this might make it more difficult for them to engage gig workers.” Overlapping Definitions

Overlapping Definitions

Pro-Business?

Pro-Business?