Winner, winner, chicken dinner: The incredible growth story of Licious

How meat and seafood brand Licious made the most of the pandemic tailwinds and now has revenue of Rs1,000 crore in its sights by March 2021. Can it get there?

Abhay Hanjura (left) and Vivek Gupta, co-founders, LiciousThe poultry business is not for the chicken-livered. Sometimes, the fears surrounding it are based on rumours, at other times they’re real. Like in January 2015 when Taiwan culled over 1.20 lakh chickens. The island nation, gripped by bird flu, was working on a war footing to contain the outbreak. By April, the fear had spread to India, when Telangana decided to slaughter 1.45 lakh birds.

Abhay Hanjura (left) and Vivek Gupta, co-founders, LiciousThe poultry business is not for the chicken-livered. Sometimes, the fears surrounding it are based on rumours, at other times they’re real. Like in January 2015 when Taiwan culled over 1.20 lakh chickens. The island nation, gripped by bird flu, was working on a war footing to contain the outbreak. By April, the fear had spread to India, when Telangana decided to slaughter 1.45 lakh birds.

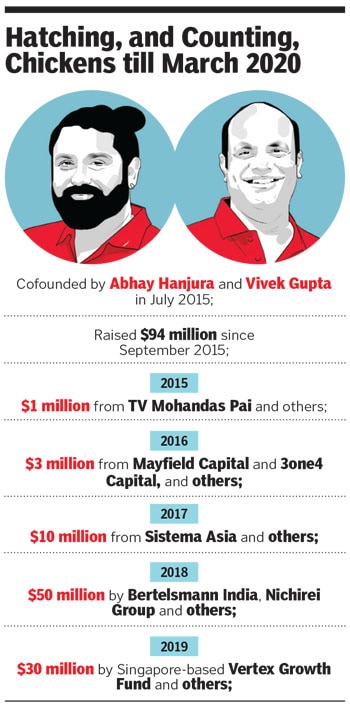

Three months later, in Bengaluru, some 600 km from Telangana, Abhay Hanjura and Vivek Gupta were ready to go against the grain. They quit their jobs—Hanjura was with Futurisk Insurance Broking Company and Gupta with venture capital firm Helion—to start meat venture Licious.

By March 2020, it seemed as if the chickens had come home to roost. This time, though, the fear around the fowl was driven by fake news. A WhatsApp message, which linked the spread of the coronavirus to eating chicken, was taking a toll on the fourth biggest chicken producer of the world. “For anything terrible happening across the world, the first casualty is poor chicken,” laments Varun Sadana, chief operating officer and co-founder of Licious.  Chicken emerged as the highest selling category during the lockdown, followed by seafood and meat

Chicken emerged as the highest selling category during the lockdown, followed by seafood and meat

Towards the end of the month, India went under lockdown, and reports of a few food delivery riders turning corona positive in top cities started trending. Prospects of doom and gloom for the poultry industry and for Licious, which had laboured to clock Rs180 crore in revenue in fiscal 2020 looked real. Sadana feared the worst.

Fast forward to September. After almost six months of living with the virus, the fear has taken on a delicious avatar for Licious. With people gravitating towards a safer lifestyle, a more hygienic form of food consumption, and neighbourhood meat shops grappling with erratic supply, Licious made the most of the pandemic tailwind by clocking a staggering Rs600 crore in revenue, a jump of over 300 percent over the previous year’s topline in just the first half. In fact, the business done by the meat and seafood brand in six months was more than what it did in five years.

Chicken, interestingly, emerged as the highest selling category during the lockdown, followed by seafood and meat. While last June and July, Licious clocked 1.50 lakh orders a month, the numbers for the same period this year stood at a million (10 lakh) per month. “This tells you how much we grew,” says Gupta. The company, he adds, now plans to leapfrog to Rs1,000 crore in revenue by March 2021.  Licious had to ensure that the delivery channel—it has its own set of riders and doesn’t depend on online food aggregators like Swiggy and Zomato

Licious had to ensure that the delivery channel—it has its own set of riders and doesn’t depend on online food aggregators like Swiggy and Zomato

The incredible growth during the pandemic didn’t come on its own. Much went behind the scenes, especially in cracking the supply chain, which had three critical components. First was getting hold of raw meat. The initial days of lockdown not only shut down everything, but also ensured confusion regarding movement of commercial vehicles. Poultry owners, hit hard by shutting down of hotels, restaurants and local markets, were in a fix as demand suddenly vanished.

The second problem was taking care of factories, which not only had to be run but, as Sadana puts it, “had to be run safely, without letting the virus in”. Lastly, Licious had to ensure that the delivery channel—it has its own set of riders and doesn’t depend on online food aggregators like Swiggy and Zomato—were safe and had not contracted the virus. The big question, he lets on, was never about demand. “It was about supply.”

The Licious team took a stab at the biggest problem first: Supply. It went back to its suppliers—Sadana calls them partners—and reassured them of taking care of the demand side, which was crippled due to the lockdown. There was only one pre-condition though. Sadana wanted a commitment: No laxity on quality.

The partners were asked to keep supplying the same stuff which they were doing before Covid, and if that meant spending more money to ensure a glitch-free supply chain, Licious was willing to go the extra mile. Members from the Licious team camped with fishermen on the southern coast to assure them that they would take care of the supply. In markets where Licious couldn’t find high quality products, such as Delhi, the startup began airlifting meat from Bengaluru during the initial days of the lockdown. “We never compromised,” he says.

After cracking the supply part, came the production challenge: To ensure that factory workers remain virus-free. Licious created a bio-bubble—something similar to what organisers of the Indian Premier League have done. Around 700 workers across all its locations were put in a bio-bubble. A hotel was reserved for staff, no guests were entertained and no movement was allowed. From the hotel, the employees came directly to the plant, and then went back to the hotel at night. “Now it sounds simple. But it wasn’t easy then,” says Sadana. The nagging fear of consumers of being exposed to the virus had to be tackled effectively. The results are for all to see—bumper growth and stickiness for the meat and seafood player that has two offline stores. “Consumers must have a good sleep,” he says. “And it comes by building trust.”

Back in Bengaluru, in May, Arjya Banerjee, 33, was taking a leap of faith in reposing trust in a meat startup. A brand consultant, Banerjee used to make her purchases from her local meat shop. The pandemic and lockdowns changed her consumption and buying behaviour. “I started buying from Licious. And now I am not going back to the butcher’s store,” she says. The fear of contracting the virus made her take a hard look at the quality of meat that the local stores were dealing with. “I can shell out extra money but not at the cost of safety,” she says. Black polythene bags—commonly used at butcher stores to pack meat—made way for smiling boxes (Licious packs sport beaming faces of its users). BLACK AND WHITEHanjura explains the black comedy. “Four things in India are sold in black polythene bags,” he says. Condoms, liquor. sanitary towels and meat.

“It’s a reflection of the socio-cultural baggage in India,” he says. Ironically, for the Kashmiri Pandit, who decided to quit his high-paying job to turn a ‘branded butcher’, the prospects looked bleak. His father threatened to disown him publicly. His father’s fear of getting stigmatised by society hardened Hanjura’s resolve. “I decided to fight the cultural hypocrisy,” he recalls, adding that he had to pay an emotional price. For the next three years till February 2018, when he and his co-founder were invited by the Harvard Business School for an address, his father didn’t disclose his profession to anybody.

It was the same story for Gupta, but with a twist. The co-founder comes from a ‘hardcore vegetarian’ family. His dad’s problem was not with the meat business. “What will I tell my friends and relatives was his problem,” recalls Gupta, who after spending a good decade at venture capital firm Helion was now determined to fight the hypocrisy. If someone turns vegan, he explains, it’s a moment of pride. “But if a vegetarian guy has to eat meat, he has to hide and eat,” he rues. For the co-founder of India’s biggest branded meat and seafood business, entertaining any thoughts of cooking meat at home are still banned.

The commonalities between the co-founders—who became friends over drinks—didn’t end with an intent to fight the hypocrisy. The duo wanted to create a brand in meat. Reason: Every product, and commodity, was getting branded. Water has Bisleri wheat flour has Aashirvaad for milk there is Amul curd has Mother Dairy there is MDH for spices and even a brand for dosa batter. “But where was a brand for meat?” asks Gupta, adding that India consumes meat worth over Rs3 lakh crore every year.

The task was not easy. Reasons: A highly unorganised sector and few know what goes into breeding a chicken. People trust a brand only when they know what goes into the making of it. In the meat business, everything was black. Nobody knew anything. “Jab marey huey murgey mein jaan daalengey toh banegi baat (when we instil life in a dead chicken, then we will stand a chance) was what Hanjura told his co-founder. The duo bootstrapped the venture, pooled in over Rs60 lakh and started Licious in July 2015. In September, the product started to roll out and the startup clocked 1,300 orders in the month. But the astonishing part happened next month: Over 90 percent of consumers came back to the platform. “This shows they trusted the quality,” he says.

The obsession of the co-founders to maintain quality made them the butt of jokes. ‘They want to sell gold-plated meat’ was one of the digs. They were unfazed and stayed put in Bengaluru for the first two years. Gupta’s background and experience as a venture capitalist came in handy in not going for reckless expansion. “It always made sense to consolidate first,” he recalls. The first expansion was Hyderabad in 2017. Over the next few years, Gurugram, Delhi, Noida were added. The move made sense. “We’re operationally profitable across all cities,” claims Gupta. The pandemic, he stresses, has pushed the company to a much higher growth trajectory.

The pandemic, reckon industry experts, has also done something unprecedented. “It has brought down the customer acquisition cost to almost nil,” says Anil Kumar, chief operating officer at RedSeer Consulting. Another windfall is high consumer stickiness, a pain point with all startups. Most of the consumers for all meat and seafood startups would not go back to the old form of offline purchase, he adds. “The trial happened on its own and the user is here to stay,” he says, adding that growth for players like Licious has leapfrogged.

But Rs 1,000 crore revenue by March 2021? The co-founders are optimistic. “ The day the black polythene bag is completely discarded from the industry would be our biggest achievement,” says Hanjura. Till then, the duo will keep fighting fear, stigma, and hypocrisy.

First Published: Oct 02, 2020, 14:21

Subscribe Now