Women and the woes of sand mining

Women of coastal communities are disproportionately affected by illegal sand mining as they face an increased burden of household responsibilities

Every day, lines of bullock carts with specially rubberised wheels cross the creek between Kihim and Awas beaches in Alibag, where many Mumbaikars now live and work, to mine vast quantities of sand unchecked.

Every day, lines of bullock carts with specially rubberised wheels cross the creek between Kihim and Awas beaches in Alibag, where many Mumbaikars now live and work, to mine vast quantities of sand unchecked.

Image: Sumaira Abdulali

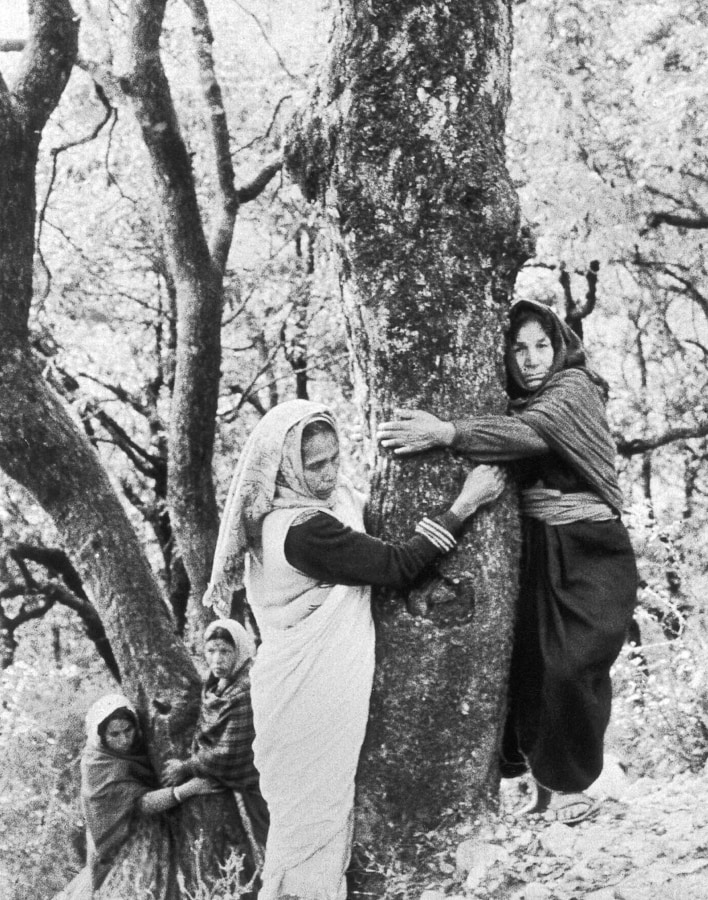

In 1973, almost 20 years before the Coastal Regulation Zone was first notified in 1992 and 30 years before I encountered the sand mafia on Kihim Beach, in Maharashtra, in 2004, it was impossible for Gaura Devi and the women of Raini, Uttarakhand, to imagine that sand mining would wash away their village in the Garhwal Himalayas. Even less likely that their Chipko Movement to save trees would inspire a movement to save sand on the Konkan coast of Maharashtra. Yet, when I felt the weight of sand press down on me, buried in the sand to protest its destruction in an awareness campaign ‘Don’t Bury the Issue of Sand Mining’ I drew inspiration from Gaura Devi and other women of Reini.

In 1973, Gaura Devi hugged her trees because she loved them. She hugged them because their lives were intimately connected, she wanted to save them from logging. Above, holy Badrinath, Kedarnath and the Valley of Flowers are in the tallest mountain range of the world. Underfoot, ancient sand scattered with shells from the ancient seabed of the Neotethys Ocean, which arose to form the Himalayas in the clash of two continents—India and Eurasia—50 million years ago.

As the women of Raini, who may never see or imagine a sea-coast, are intimately connected with seashells, we who live by the sea are intimately connected with Himalayan glaciers that flow to the coasts, grinding rocks along the way, bringing water and sand with them. “Different forms of environmental change are intertwined," says ‘Making Peace with Nature’ the United Nations’ blueprint on the Climate Emergency, released in 2021. “Earth’s environmental emergencies must be addressed together to achieve sustainability."

In 2003, I first became aware of sand mining as a serious environmental threat when I saw sand hauled away from Kihim Beach. Giant craters replaced soft white sand I had walked on my whole life for me this beach I loved, without sand, was unthinkable.

In 2012, the Women Human Rights Defenders International Coalition Report (WHRDICR) carried the two attacks on me by Alibag’s emerging sand mafia (at Kihim in 2004 and Mahad in 2010) as a case study to demonstrate the links between women and sand mining. The WHRDICR said, “As is typical in rural India, women have no voice in the male-dominated sand mining business that is affecting their homes and villages—unless activists intervene and many activists taking up these issues in India are women."

Cement-concrete using sand is our modern-day go-to for construction. Modern cement-concrete building requires sand, stone, ground naturally or through an industrial process, into irregular particles, to give strength to our civilisation’s built infrastructure. The high demand and easy availability of sand and stone make them the second most extracted materials in the world, after water.

Beach sand mining was illegal since 1991 when the Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Rules were first notified 31 years ago. Sand mining happened nevertheless, surreptitiously. Instead of cracking down, the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change seeks to legalise beach sand mining and accelerate the existential threat to our most beautiful Indian beaches. Is India sacrificing long-term interests for short-term gains?

Every day, lines of bullock carts with specially rubberised wheels cross the creek between Kihim and Awas beaches in Alibag, where many Mumbaikars now live and work, to mine vast quantities of sand, unchecked. Although coconut trees have fallen across the eroded beach and high tide sprays salt-water 10 feet high, complaints do not result in any serious action.

Kihim beach.

Kihim beach.

Image: Sumaira Abdulali

In 2017, investigative journalist Sandhya Ravishankar uncovered illegal sand mining on beaches near Chennai in Tamil Nadu. She said, “The journey of uncovering illegal beach sand mining has been bitter, though also filled with victories big and small, it has broken old relationships and built new ones. Perhaps it is, in effect, a microcosm of a turbulent life."

Indian cities like Mumbai and Chennai already face threats of drowning by 2050 because of sea-level rise. Sand mining will remove natural barriers, hasten the process and accelerate this threat. It will worsen the effects of climate change accelerate the destruction of coastal fishing livelihoods destroy farmlands, adversely affect ground-water tables through saline ingress destroy holiday and recreational facilities impact biodiverse habitats of marine, terrestrial and bird life.

Advocate Ishwar Nankani, who filed public interest litigation (PIL) against illegal sand mining pro bono for Awaaz Foundation in 2006, says, “In the last several years, sand and stone quarrying was responsible for landslides in Kerala and Maharashtra. Legalising beach sand mining to the private sector will legitimise an environmentally destructive activity."

Ironically, in a closed loop of destruction, sand mining threatens the very infrastructure it is mined to build. In Mahad, where I encountered the sand mafia over a decade ago, sand dredgers were found under a bridge that collapsed in 2016. In Uttarakhand, several important bridges collapsed when sand was mined excessively nearby in 2021.

Sand mining contributes to, and worsens, the effects of climate catastrophes too. Sand is required for building. After every climate disaster, it is also required for re-building, further increasing environmental and human costs. Women of coastal communities are disproportionately affected, according to multiple reports of the United Nations, because women face an increased burden of household responsibilities.

In Uttarakhand, where sand mining was directly responsible for the flooding of the Ganga and huge loss of property and lives, an investigative report for The Third Pole by Monika Mondal says, “The Centre’s sand mining framework reports that revenue from the sale of sand in Uttarakhand was Rs 1.735 billion (about $23 million) in the financial year 2014-15, and nearly doubled to Rs 3.353 billion in 2016-17, the latest year for which figures are available."

“Sand is free, it’s lying around, and anyone can plunder it. This makes sand mining a difficult issue to control." says senior counsel Chander Uday Singh, who appeared pro bono with Ishwar Nankani in the first PIL against sand mining in 2006 in the Bombay High Court. He goes on to say, “Major rivers, including the Ganga, Yamuna, Godavari and Kaveri are being plundered unchecked already. High demand and easy availability of sand for construction is a cause of massive environmental degradation and human rights violations, more known now than they were when Sumaira was first attacked by the sand mafia on Kihim Beach in 2004 and 2010."

Natural disasters like floods and landslides are “putting a strain on the state’s economy," said Chief Minister of Maharashtra Uddhav Thackeray, in October 2021. Ironic that sand, extracted recklessly to build the infrastructure for economic growth, is itself placing the economy at risk.

In the absence of official figures, the real value of sand extracted for construction can only be estimated as a percentage of India’s building plans. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has announced $1.3 trillion investments towards building cement-concrete infrastructure in the Pradhan Mantri Gati Shakti Master Plan. This infrastructure cannot be built without sand or a sand-substitute. The corresponding cost of sand makes it our single largest commodity.

Awaaz Foundation protests against illegal sand mining.

Awaaz Foundation protests against illegal sand mining.

Image: Awaaz Foundation

The government is our largest builder of infrastructure. Nevertheless, it has never conducted a full audit of sand availability or matched it with the requirements for our ambitious development plans. There have been no studies on the monetary value of the sand that will be needed for construction and otherwise. While sand continues to be stolen from our rivers and beaches, sand mining has been legalised to meet increased demand.

CoP26, the crucial climate change conference at Glasgow, concentrated on phasing out coal and curtailing deforestation to cut emissions and prevent the most devastating impacts of climate change by 2050. However, CoP26 did not consider sand mining or emissions from cement-concrete construction.

India is hastening to catch up with the failed development models of ‘developed countries.’ These models are highly polluting and have led to the Earth’s climate crisis, the most serious existential threat facing humans today. Today, we better understand the very real costs of such polluting models of development. Yet, we choose further disaster when we do not factor environmental, financial or human costs of climate change adequately into our growth models.

The sand mafia has murdered, accidentally killed or attacked hundreds of people including activists, journalists, government officials, police, even members of the elected Assembly. Of the 193 people killed because of sand mining between January 2019 and November 2020, 80 percent of the 95 who drowned were children because they were unaware of sandpits underwater.

“There is no credible assessment, neither environment assessment nor social assessment, of river sand mining in India, which can only be credible if there is an independent assessment. In absence of that, we are moving in darkness. We don’t even understand what the implications of river sand mining are," says Himanshu Thakkar of South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers & People (SANDRP), who has studied India’s rivers for three decades.

Monika Yadav of Uttar Pradesh understands these implications first-hand. “When sand was forcibly removed from our family’s fields, I had trouble feeding my children. I have to walk further to fetch water every day. My husband [Brijmohan Yadav] protested. Then he was attacked and now we are scared in our own home. Our whole family is suffering."

A fact-sheet on the website of the United Nations says, “Women and girls bear the burden of fetching water for their families and spend significant amounts of time daily hauling water from distant sources... given the changing climate, inadequate access to water and poor water quality does not only affect women, their responsibilities as primary givers, and the health of their families… increases the over-all amount of labour that is expended to collect, store, protect and distribute water."

Indian women suffer disproportionately from the effects of climate change. They are forced to walk further to fetch water, to care for children and the elderly through climate-related floods and droughts. Yet, like their children who will inherit the world of climate catastrophe we leave behind, they have the least say in controlling climate.

An item on the Provisional Agenda of CoP 26 ‘Gender and Climate Change’ confirmed the importance of women in planning. Decision 9/CP.24, “Urges Parties and non-Party stakeholders to mainstream gender considerations in all stages of their adaptation planning processes, including national adaptation plans and the implementation of adaptation action, taking into account available guidance."

Nevertheless, “Women are often left out of high-level policy discussions and are unable to fully participate despite their expertise," says Elsa Marie D’Silva, founder of Red Dot Foundation and author of She Is, which features 33 Indian women working on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. “Having capability and opportunity, we now need intention and investment."

Late Shabnam Siddiqui, executive director, UN Global Compact Network India, concurred: “Only the complete participation of women, who literally hold half the sky, will ensure… SDGs and their targets have a real chance of achievement."

Josy Paul, chief creative officer of BBDO India, who designed the campaign ‘Don’t Bury the Issue of Sand Mining’ for Awaaz Foundation, says, “Sand mining is an ‘out of sight, out of mind’ issue, though it impacts all of us, whether we know it or not. The challenge is to bring sand mining into the public consciousness as a mainstream environmental threat, which directly affects urban and rural people, men and women, in their day-to-day lives."

Their traditional roles as carers also ensure that women lead in caring for the environment. The UN stressed the impacts and role of gender, calling for “sensitive planning". Professor Suzanne Simard of the University of British Columbia describes heritage trees as “mother trees" that “send messages of wisdom on to the next generation of seedlings".

Chipko movement.

Chipko movement.

Image: Bhawan Singh/The India Today Group via Getty Images

In 2021, 48 years after his grandmother Gaura Devi inspired environmental movements across the world when she hugged and protected the trees she loved, her grandson Sohan Singh filed a petition to protect his village of Raini in Uttarakhand after two devastating floods.

In 1973, the women of Raini could not know the multiple challenges their forest would face or how their demonstration of love for their trees would inspire multiple environmental movements to protect a redwood forest in California, an Andean cloud forest in Ecuador. They could not imagine their action resonating decades later when a glacier burst in Nanda Devi and floods destroyed Raini itself.

On Women’s Day, we celebrate women: We celebrate the women of Raini and their Chipko Movement. Their inspiration lasts.

The writer is convenor, Awaaz Foundation.

First Published: Mar 08, 2022, 10:45

Subscribe Now