It was a match made in heaven. She was a woman of experience—a blue-chip international investment firm, with smart professionals and deep pockets. He was young yet worldly-wise, an innovative Indian startup with a unique consumer-focussed online business, which had received strong customer validation, and was looking for capital to scale up.

After a happy first 8-10 months, the regular bickering of a compatible duo escalated to worrying levels. Consider one of their latest board meetings, which lasted for nearly eight hours. There were no smiling faces or encouraging words from investors instead, voices were raised, tables thumped, shareholders’ agreements pointed at and papers strewn around, amidst accusations from both sides. Investors said they were not fully informed about the expenditure plan while promoters insisted that they were not being allowed to run the company in their own way. The root cause of the conflict was that the company had raised capital on the basis of a particular business model that had enticed the investors. But soon after the funding, the startup diversified into a somewhat related business, which started to hurt the company’s bottomline. The investors asked for a rollback but the promoters refused.

This deadlock continues but the differences have not assumed the ugliness of a public spat. Think Housing.com. The overt tug-of-power there should prove to be a cautionary tale for investors and startups alike.

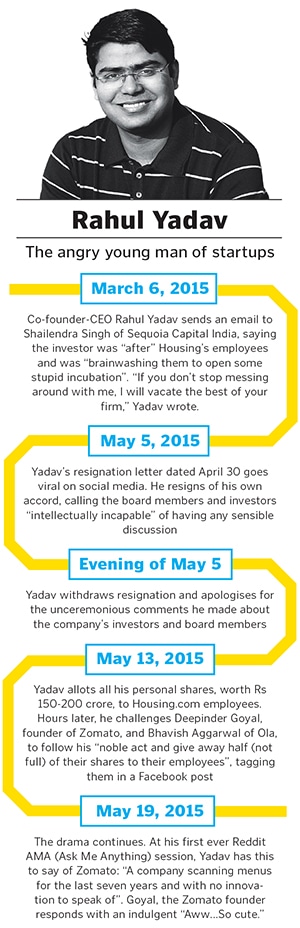

In the last few weeks, one of their founders and CEO Rahul Yadav showed open contempt towards his investors, resigned and subsequently resumed services at his realty search venture. He has given up all of his equity stake to his employees, and dared his counterparts at Zomato and Ola to do the same. The jarring notes emerging from a leading Indian startup is a sign that this world—marked by multi-billion dollar valuations, high-cost projects, overnight success stories, tempestuous relationships and public slandering—is ripe for implosion.

Take the case of a Delhi-based startup, whose promoter believes in accelerated expansion as scale will help garner better valuation for the next round of funding, besides ensuring a larger geographical presence. But investors prefer a more cautious approach and are averse to bridge funding (money raised between funding rounds). The incompatibility in business philosophy and personalities has created a sour environment for both parties. “Companies are meta-morphosing so fast and pivoting from one scale to another in a matter of months. Things that stand true today may change tomorrow,” says a stage-agnostic investor, who does not wish to be identified.

While humongous growth and accelerated scale has given India several billion-dollar startups in the last five years, it has also given rise to a new class of successful, smart, innovative, courageous and aggressive entrepreneurs.

These traits are, however, akin to a double-edged sword. Investors may seek a promoter’s aggression and confidence in running the business, but those attributes will willy-nilly come into play in their interactions too and lead to discord.

When Yadav called his board members and investors “intellectually incapable” of sensible discussion in his resignation email on April 30, it was not a lone instance of his disdain towards them. Yadav had earlier taken public potshots at Shailendra Singh, managing director of Sequoia Capital India, saying the investor was “after” Housing’s employees and was “brainwashing them to open some stupid incubation”. “If you don’t stop messing around with me, directly or even indirectly, I will vacate the best of your firm,” the 26-year-old Yadav had said.

On May 5, Yadav withdrew his resignation from Housing.com and apologised, but there has been little perceptible change in his style. On May 13, he said he was allotting all of his personal shares (pending board approval) worth Rs 150-200 crore to the 2,251 employees of Mumbai-based Housing.com. Hours later, Yadav went a step further and challenged Deepinder Goyal, founder of Zomato, and Bhavish Aggarwal of Ola to follow his “noble act and give away half (if not full) of their shares to their employees” tagging them in a Facebook post. While Aggarwal is an IIT-Bombay alumnus, Goyal is a graduate of IIT-Delhi. Yadav dropped out in his final year from IIT-Bombay in 2011.

For a company that was being labelled the next $1-billion firm, Housing.com finds itself trapped in many controversies, including a defamation notice served to Yadav and the company’s board by Bennett Coleman and Company Ltd (BCCL) and one of its co-founders Advitiya Sharma getting embroiled in a car accident that resulted in the death of two of the company’s employees.

Yadav continues to court controversy, for instance during his first Reddit AMA (Ask Me Anything) session on May 19. The AMA sessions hosted on Reddit, a popular social networking site, allow users to ask key personalities, quite literally, anything. During the session, Yadav was asked his opinion of Zomato, a global player in the online restaurant search business. His answer was biting: “A company scanning menus for the last seven years and with no innovation to speak of.” Goyal responded with an indulgent “Aww. So cute.”

![mg_81393_housing_280x210.jpg mg_81393_housing_280x210.jpg]()

At least one investor speaks of his initial impression of Yadav as a brilliant guy behind a computer, but not one who would listen to others easily. This investor has passed on at least three investment opportunities in Housing.com. “It was clear that it would either be a $10-billion game or a zero. He (Yadav) is a maverick guy… a firestorm. Strong personalities evoke strong reactions. For instance, if Housing.com today goes for a $1-billion public offering, people will say he speaks his mind,” says this investor on condition of anonymity.

Investors are treading far more carefully, especially when selecting a working partner. “The most important thing for us is whether we can find an entrepreneur we can work with or not. They should be independent in their decision making, but open to listening, discussing and debating crucial matters,” says investor and entrepreneur Sanjay Swami.

However, Amit Agarwal, co-founder of NoBroker, an online home-rental platform, says that while “humility” was a desirable attribute even two years ago, today investors judge entrepreneurs differently. “[Investors prefer] someone who is brash but can talk about lofty goals… they love entrepreneurs who project that they would be the next Facebook or Google,” says Agarwal, 37, an IIT-Kanpur and IIM-Ahmedabad graduate. Bangalore-based NoBroker raised $3 million in a Series-A round in February this year. SAIF Partners and Fulcrum Ventures participated in the round.

Entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs of Apple, Sean Parker of Napster and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg are idolised, not just for their success but also for their in-your-face attitude. But donning a hoodie and showing arrogance is merely imitating the superficial. “The psychology of fame and power always makes one do impulsive things. The whole psyche of ‘nothing will happen if I do this’ plays in the mind,” says Jaya Rahul Pujara, lecturer of psychology at Pune-based educational institution FLAME (Foundation for Liberal And Management Education). “They want to compare themselves with the best in the business and not the Number 2.”

Housing.com, which is just about three years old, has so far raised $130 million from investors like Japan’s SoftBank and US-based Falcon Edge, besides Nexus Venture Partners and Helion Venture Partners. It is valued at around $250 million.

“These are young, immature first-time entrepreneurs who got seduced by high valuations,” says Mahesh Murthy, a startup investor. “One mistake that the promoters made was that they went for higher valuations rather than a supportive VC.” Murthy, however, holds the investors equally responsible. “One pertinent question for investors is—what was your judgement on the promoter? Were you just a money bag for them? Your investee company had no respect for you,” he says.

Investor, serial entrepreneur and chairman and co-founder of Portea Medical K Ganesh says early success often gives a young promoter a false sense of achievement. “Raising money is just the start of the game there is no glory in it. The glory is in building a strong and credible company. There is an adrenaline rush when you are 20-something and raising millions of dollars and people are chasing you,” says Ganesh. Washing dirty linen in public will only give the company a bad name, he adds. “A potential investor will be very wary about the company. It also reflects poorly on existing investors who couldn’t control a situation like this, which is completely unacceptable.”

It doesn’t help that the Indian market is seeing an onslaught of what the industry calls “tourist investors”. These are global investors who invest heavily in Indian startups, particularly in the consumer internet space. They don’t have a presence in India and fly in just to sign deals. These deep-pocketed investors tend to have a hands-off approach.

“There is no time spent with promoters. Entrepreneurs on their part feel these are ‘easy’ guys—you can sell anything to them. Think of it along the same lines as long distance relationships many fail,” says a Mumbai-based investor on condition of anonymity.

Further, the early stage in India has seen many more changes than growth- or late-stage. It’s not just seed funds and venture capital funds that are infusing innovative firms. Deep-pocketed investors including hedge funds like Steadview Capital, strategic investors like eBay and Rocket Internet, big-ticket investors like Tiger Global and SoftBank, are taking exposure to these startups too.

About five years ago, a startup’s board would typically have two to three investors. Now, a fast scaling, high growth startup ends up with a larger number of board members, sometimes as high as a dozen. This is particularly true in the case of ecommerce and technology firms, which grow on a month-on-month basis. A startup board of such firms would typically have late-stage investors, strategic investors and venture capitalists.

“The problem lies with the number of participants these days. These are different asset classes, their interests are poles apart. Differences are at their peak right now, if you ask me. So many different variables in a startup board like today have never existed ever before,” says another Mumbai-based investor.

An early-stage investor on the board of a startup would aspire for returns of over 10x to 100x, depending on the company and the time they have put in. They usually invest for six to eight years or more. A strategic investor wants to gain entry into a new geography or seeks financial returns. A hedge fund or a late stage fund invests with an eye on a public offering, a massive up-round or strategic sale.

Despite the presence of varied asset classes as their financial backers, promoters tend to trust only one or two investors. This trust is not a function of the capital invested by an entity but a result of personal compatibility and a common vision for the future. In such a situation, a promoter may not pay much heed to other investors, thus creating conflicts in the process.

Some experts point out that too much money, too soon, impacts a management team’s vision. Some say the Housing.com imbroglio will be a reality check for investors, who will now do better due diligence. Others say it is highly unlikely that the company’s investors will let it go down. “They can’t afford to take a reputational risk,” says a Mumbai-based investor.

Over-funded companies have attendant risks, like slower-than- promised growth. While signing a deal, promoters may have promised growth of 500 percent. In reality, the growth turns out to be only about 100 percent. Such differences can rattle investors, forcing them to ask difficult questions to the promoters and prompting decisions like reduction in capital expenditure. This is usually tricky and can be handled by sticking to the letter of the agreement or by working matters out through inter-personal skills.

Most investors prefer the latter option. Dragging promoters to court doesn’t work in India as it often takes several years to settle an issue. “You swallow your ego, be politically correct and sometimes put your foot down… that’s how it works,” says the investor, quoted first in this story.

Genteel bargaining is also not out of question. For example, a promoter of an FMCG startup recently wanted to place an all-India jacket advertisement in a leading daily. His plan was to grab eyeballs and also indicate to the world that he has arrived. The investors were not too keen as the advertisement was expensive but finally relented on one condition. “This time, we agreed to your decision next time, we will take the decision and you will back us,” they told the promoter.

A little give-and-take is the first step in resolving this uneasy relationship. Ask any marriage counsellor.