How the 2009 Section 377 judgement changed the LGBTQ discourse in India

The 2009 judgment that overturned Section 377 and decriminalised consensual homosexual activities set the stage for future verdicts and inclusiveness for the LGBTQ community

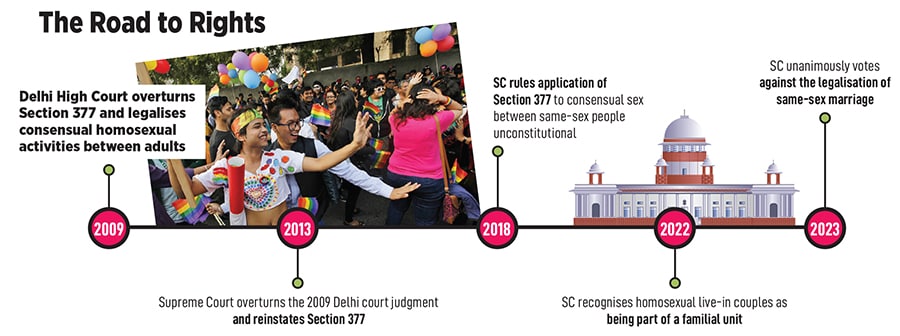

On July 2, 2009, when the Delhi High Court overturned the 150-year-old Section 377 and legalised consensual homosexual activities between adults, it was a judgment that was momentous in more ways than one.

Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code criminalises sexual activity “against the order of nature" and the 2009 judgment not only unleashed hope among the LGBTQ community but also provided a new language to sexuality. “The jugdment looks at sexuality not within the language of being dirty or despicable, but rather within the lens of dignity, and that’s a shift. It altered the terms of the debate itself," says Arvind Narrain, lawyer, founder member of the Alternative Law Forum, and queer rights activist. It went on to change the way things were articulated in the media, in conversations, in the public sphere and private.

It had been a decades-long movement initiated in 1991 by the AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Andolan and revived by Naz Foundation, which filed a public interest litigation in the Delhi High Court in 2001. After 2009, as more and more people came out, an ecosystem of allies and industry bodies started coming together, and companies launched inclusive policies, programmes and processes.

When the Supreme Court (SC) overturned the 2009 Delhi court judgment and reinstated Section 377 in 2013, it came as a shock. The ruling came despite submissions to the SC by mental health professionals who said that queer clients suffered psychological distress due to the threat and social censure posed by IPC 377. “There’s a beautiful description by [writer] Vikram Seth, who said, ‘it’s a bad day for law and love’," says Narrain. But 2009 had set the stage and there was no going back—for the community, companies or the ecosystem.

“I must salute the companies that did not go back in the closet," says Parmesh Shahani, head of Godrej DEI Lab and author of Queeristan. “There were so many companies that between 2009 and 2013 had come out with their support for LGBTQ employees, and to their credit, many of them did not step back."

The Naz Foundation filed a curative petition and the matter came up for hearing in the SC in 2016. In 2018, the application of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code to private consensual sex between same-sex people was ruled unconstitutional by the SC, thereby decriminalising homosexual activity. The 2018 verdict not only built on the 2009 jugdment but also took a couple of steps forward, invoking the language of privacy, dignity and equality, and also an apology for the LGBTQ community for the suffering which was caused by the law.

Justice Indu Malhotra said: “History owes an apology to these people and their families." While Justice DY Chandrachud said: “It is difficult to right a wrong by history. But we can set the course for the future."

That future involves building on more equal rights—including marriage, and legal and financial rights. In 2022, when the SC provided limited equal rights to live-in relationships, it also recognised homosexual live-in couples. But in October 2023, it unanimously voted against the legalisation of same-sex marriage.

Also listen: What"s next for same sex marriage rights?

“It’s like a roller-coaster going up and down. That judgment was a disappointment. But the saving grace is that there is a minority judgment which provides a way forward."

Though the heart of it is that marriage cannot be interpreted to include LGBTQ persons, “the minority advocates for the right to establish an intimate union under Article 19 (1) C", says Narrain. “It’s not the end of the story, even within the courts of law, because the community keeps pushing the boundaries at every point."

Possibilities also exist in the Congress election manifesto that supports civil unions between couples belonging to the LGBTQ community.

Though challenges remain and there is a long way to go, there has been progress. “It’s a different landscape today than it was five or six years ago," says Narrain.

Since 2018, there have been further changes in attitude—whether in families, in the depiction of the community in the media, films and OTT or in educational institutions and workplaces. Thanks to awareness and support groups, a lot of it is also fuelled, says Shahani, by the younger generations, for whom inclusiveness is a given. For them, “the inclusion and equality is non-negotiable".

First Published: May 30, 2024, 12:54

Subscribe Now