'N Chandrasekaran has tied Tata's future to the future of India'

Natarajan Chandrasekaran, who became CEO of TCS 15 years ago, has risen in stature to lead the entire Tata Group, balancing corporate returns and national priorities

Auto enthusiasts in India noted a simple data point for the month of March, in news reports in early May, that signalled nothing short of a dethronement. Tata Punch, often referred to as a “micro SUV", surged past the Maruti Wagon R to become India’s top selling car. In April, the Punch stood tall—like its higher ground clearance demanded—to repeat that feat.

Industry watchers would have noted the rise of Tata Motors over the last few years to become India’s third-largest automaker. But displacing a Maruti at the top of the country’s bestsellers’ list is bringing the message home to every upwardly mobile household—a Tata car is an aspirational vehicle now.

“It’s really noteworthy how Chandrasekaran has tied the Tata Group’s future to the future of India," says Rishikesha T Krishnan, professor of corporate strategy at the Indian Institute of Management-Bangalore.

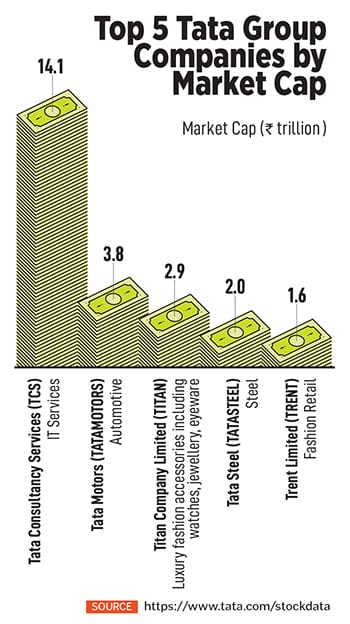

Tata Motors’ rise, within the Tata Group, isn’t isolated. From steel and manufacturing to hotels to online commerce, and, of course, the flagship IT services business, N Chandrasekaran, chairman of Tata Sons, the holding company, is shaping several multibillion-dollar operations with an eye to the future.

In January 2022, Air India returned to the Tata fold.

While companies such as Tata Consultancy Services and Tata Motors usually get more news coverage, something that’s less widely noted, but of strategic importance, is the group’s growing footprint in hi-tech manufacturing, Krishnan says. An example is the 2022 acquisition of a controlling stake in Tejas Networks, which has intellectual property in communications hardware.

Then there is the semiconductor play that Chandrasekaran revealed in January, at an event with Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the audience. The Tatas have committed ₹91,000 crore ($11 billion) to two semiconductor plants—a commercial scale wafer fab and an assembly and testing unit—in partnership with a Taiwanese company.

Then there is the semiconductor play that Chandrasekaran revealed in January, at an event with Prime Minister Narendra Modi in the audience. The Tatas have committed ₹91,000 crore ($11 billion) to two semiconductor plants—a commercial scale wafer fab and an assembly and testing unit—in partnership with a Taiwanese company.

In aerospace, Tata Advanced Systems is hitting new milestones and expanding partnerships with the world’s biggest players, including Airbus, Boeing and Lockheed Martin.

“He is very closely aligning the group with the national priorities, if you will," Krishnan adds. Chandrasekaran has raised the profile of the Tata group as a “strategic conglomerate" for India and “that’s a pretty big repositioning".

At Tata Steel, for example, while it has operations in the Netherlands, the UK, and Southeast Asia, “our future strategy centres around expanding in India", Jayanta Banerjee, group chief information officer of Tata Steel, told Forbes India in June 2023.

Tata group’s digital strategy under Chandrasekaran is also something that stands out, Krishnan says. “It’s still work in progress, but if you look at the various assets they are pulling together, from BigBasket to 1mg to Tata Neu, it’s an interesting combination of products and platforms, which could ultimately add up to quite a strong digital presence."

And soon, all these could be pulled together in some new offerings on an Apple iPhone, if Tata’s partnership with the US consumer tech giant expands from assembling the smartphones to bundling services.

Chandrasekaran turns 61 in June. He is the fifth of six children born to agriculturist parents in a small town called Mohanur in Tamil Nadu. His father trained to be a lawyer, but family circumstances led him back to the lands, Chandrasekaran said in an interview in 2020.

He went to the only public school in town, where the medium of instruction was Tamil. Later, he attended Coimbatore Institute of Technology and received a bachelor’s degree in applied sciences, and completed a master’s degree in computer applications at the Regional Engineering College in Tiruchirappalli.

Chandra, as those in his circle call him, joined TCS as an intern in 1987. It’s the only company he’s worked for. He rose through the ranks to become COO in 2007 and CEO in 2009—the youngest CEO of a Tata company in the storeyed conglomerate’s rich history. He took over TCS’s reigns from his mentor S Ramadurai, just as the world was reeling from the global financial crisis. He’s credited with putting in place TCS’s now-famous industry service units organisational structure that many credit with the company’s growth since then.

TCS was at about $6 billion in FY09 revenues, in comparison to Infosys’s $4.7 billion and Wipro’s $3.8 billion. When Chandrasekaran left to run the Tata group, in 2016, TCS’s FY16 revenues were at $16.5 billion, versus $9.5 billion at Infosys and $7.3 billion at Wipro.

Only US-headquartered India-heritage rival Cognizant Technology Solutions—under the charismatic young CEO Francisco D’Souza—grew at a faster clip from $2.8 billion (calendar 2008) to $12.4 billion (calendar 2015).

In 2016, a bitter spat between the Tatas and the single largest shareholders Shapoorji Pallonji family led to the exit of the late Cyrus Mistry as the then chairman of Tata Sons. Chandrasekaran, who had been on the board of the company from the previous year, was named to the top position.

He thus became the first professional to head Tata Sons who had no familial ties to the Tatas. Chandrasekaran is a recipient of India’s Padma Bhushan, and the Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur, the highest civilian award of France.

Growing up in a rural area gave him a sense of how tough it is for people to find jobs, Chandrasekaran says in a Netflix documentary titled Working: What we do all day, hosted by former US President Barack Obama, released last year.

Lack of access equals lack of opportunity and therefore the use of technology is going to be critical to create a level playing field, he says. “It’s about leveraging the scale, size and equity that Tata enjoys and hopefully play our part in solving some big societal problems."

On the way forward, “it’s a pretty exciting time. I think this country has come a long way since independence in the last 75 years," he says. While India has made much progress on economic growth, literacy and life expectancy, there’s so much more to do ahead.

“Sustainability, how India handles it is going to be so important not only for India but the whole world, because of the size. And we have to do this at the same time when we have to lift at least 300 million people out of poverty."

First Published: May 28, 2024, 11:55

Subscribe Now