Ninety One Cycles: Putting a dent in India's cycling culture

Two brothers engineered their way to put Ninety One Cycles on a high-growth and profitable track

Sachin Chopra got up at 3 in the morning. “How can my mother be wrong?" he asked himself. It was 2016. For the first time in his life, Chopra was having sleepless nights. “She has never been wrong," he reasoned, as he gulped a glass of water. It was pitch dark outside, and the former managing director at Everstone Capital was having a hard time battling the haunting thoughts buried somewhere in his subconscious. “Cycle mat bana beta [Don’t make cycle]," was a pointed advice by his mother when Chopra, an engineer and a private equity (PE) top dog with stints at Warburg and General Atlantic, decided to turn entrepreneur at 40.

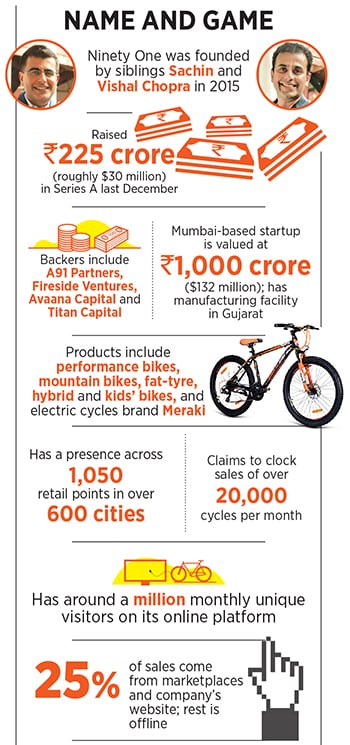

Friends and colleagues too pedalled their opinion, and concern. “Bechara kya ho gaya isko. Wharton ka padha hua cycle bana raha hai [Pity, what has happened to him. He studied at Wharton and now he’s making cycles]," was the shock and disbelief among many when they got to know about Chopra’s move to start Ninety One Cycles along with his engineer brother Vishal in 2015.

Tonnes of unsolicited advice and suggestions, though, had little bearing on Chopra, who even shunned the option of joining the family business of textile processing in Ahmedabad. The engineer, who came back from the US in December 2007 as vice president of Warburg Pincus, wanted to do something different, and something from his country of birth. In 2015, the Chopras started bootstrapped, pumped in ₹5 crore and formed the company. “I wanted to give $1,000 riding experience at a $150 price point," he says. His vision, and mission, both stunned people around him.

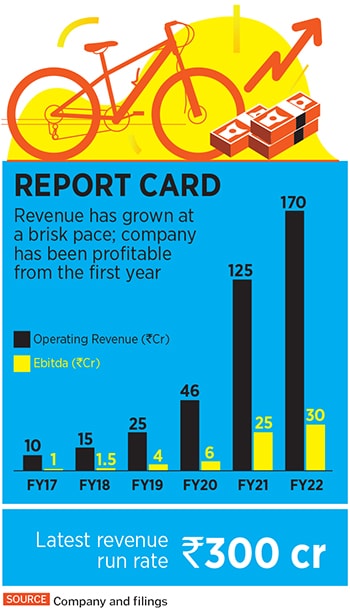

Three years later, in 2018, it was time for the VCs to get astonished. The reason was entirely different. “What’s your cash burn?" was the question posed by most of the funders to the PE veteran who rolled out his first product in October 2017 and was now looking for the first round of institutional funding. Chopra’s reply made their jaws drop. “We are over 20 percent Ebitda positive," he said “Are you sure? Have you got your figures right," was the response from the other end. “We generate cash," said Chopra as his face lit up with an impish glee. The PE biggie was enjoying the conversation. When you have to confuse a VC, he shares a secret, you should just tell that you are Ebitda neutral. “Neutral means zero, so he will get confused," he smiles. Some did get baffled. A few stopped asking questions when Chopra started taking a dig. “We are Ebitda negative, but cash flow positive," he said with a self-satisfied smirk.

Meanwhile, back in 2015, Chopra had little to smile. Starting at 40 meant an uphill ride. And he knew how steep the ride was. “When you are 40, you don’t have any runway to fail," he says. What this meant was selecting a business that didn’t need continuous pumping of money to survive, a venture that would cater to millennials and Gen Z, and a zone where Chopra could execute his engineering skills. A not-so-obvious product—cycle—emerged as the obvious choice. The more people tried to nudge him to stay away from cycles, the more Chopra got determined to ride the bicycle.

Reasons were many. Chopra explains. First, the business could be scaled. India is the second-biggest cycle maker in the world, and produces over 1.5 crore units every year. “It’s a ₹15,000-crore market," he says. What was most encouraging was the fact that the average selling price of cycles—especially premium and kids—had been increasing regularly. The segment over ₹8,000 had been clocking heady growth. “Our scalability part was answered," says the engineer. Second, the segment was ripe for disruption. “Most of the existing players never innovated," he says. What this meant was a huge opportunity to come up with differentiated products. “We are engineers. We cannot sell onion hair oil or aloe vera cream," he contends. The idea of contract manufacturing and not having control over production was a big no from day one. “Most of the washing machines look the same," he says. The upside in the business of cycles was something that everybody missed. The engineer brothers, though, were trained to spot a pattern.

Reasons were many. Chopra explains. First, the business could be scaled. India is the second-biggest cycle maker in the world, and produces over 1.5 crore units every year. “It’s a ₹15,000-crore market," he says. What was most encouraging was the fact that the average selling price of cycles—especially premium and kids—had been increasing regularly. The segment over ₹8,000 had been clocking heady growth. “Our scalability part was answered," says the engineer. Second, the segment was ripe for disruption. “Most of the existing players never innovated," he says. What this meant was a huge opportunity to come up with differentiated products. “We are engineers. We cannot sell onion hair oil or aloe vera cream," he contends. The idea of contract manufacturing and not having control over production was a big no from day one. “Most of the washing machines look the same," he says. The upside in the business of cycles was something that everybody missed. The engineer brothers, though, were trained to spot a pattern.

Fast forward to March 2022. Ninety One Cycles has put the pedal to the metal. From ₹10 crore in operating revenue in FY17, it jumped over four times in FY20 to close at ₹46 crore. Then came the pandemic, and the revenue grew furiously to ₹125 crore in FY21, and is likely to close FY22 at ₹170 crore. “We are still Ebitda positive," Chopra smiles, adding that the brand sold over 1.7 lakh units in FY22, is clocking a revenue run rate of ₹300 crore now, and the target for FY23 is to sell five lakh units. “We proudly put 91 on our bikes—91 is the country code of India—because it’s a world-class product made in India," he beams. For long, Chopra underlines, cycles in India were not aspirational. In the US and Europe, even a billionaire uses a cycle for commuting, fitness and unwinding. “To me, that was the big opportunity in India."

Back home, the pillion riders—VCs who bet on Ninety One—are having a great time. Vinay Singh, partner at Fireside Ventures, explains how he spotted an opportunity in backing Ninety One. Any industry that is large, hasn’t seen innovation, and has deep pools of margin is ripe for disruption. When somebody with a background like Sachin, he lets on, comes in with deep investing experience, the game changes. “He has seen multiple stories play out, has deeply studied the market and has backed his conviction to the hilt," says Singh, adding that the icing on the cake is the sustainable and profitable way in which the co-founders have run the business.

Singh explains why running a profitable cycle business matters. If one has a venture in a high-frequency category such as FMCG or cosmetics, the consumer will buy a brand multiple times in a year. Therefore, a founder can burn a little extra, acquire the customer and then develop a deeper, ongoing relationship. However, in brands with low frequency of purchase, one has to think about profitability from the beginning. “You’ve got to make money on every transaction," he adds.

Singh explains why running a profitable cycle business matters. If one has a venture in a high-frequency category such as FMCG or cosmetics, the consumer will buy a brand multiple times in a year. Therefore, a founder can burn a little extra, acquire the customer and then develop a deeper, ongoing relationship. However, in brands with low frequency of purchase, one has to think about profitability from the beginning. “You’ve got to make money on every transaction," he adds.

Making money, though, can only happen when one has a differentiated product. VT Bharadwaj, general partner at A91 Partners, points out how Ninety One stayed away from plain vanilla products and the gambit paid off. “Ninety One has emerged as a strong brand with deep distribution backed by solid manufacturing capabilities," he says. Bharadwaj knew Sachin from his Warburg-Everstone days. Apart from his deep passion about manufacturing and building from India, what helped him get into cycles was a realisation that the incumbents have largely looked at the product only as something meant for transportation. Recreation, fitness and premium end of the bicycle was something which was not on the radar of many. “He was early in spotting the trend," he says.

Thanks to the pandemic, the right person got to meet the right timing. The market for premium and kids’ cycles exploded in 2020. While in FY18, India produced 90 lakh cycles standard—or regular—cycles, premium and kids made up 41 lakh and 18 lakh, respectively, according to data by ratings agency Crisil. While the numbers for the next fiscal jumped to 45 lakh for premium, kids’ remained steady at 18 lakh. Then came a dip in FY20. Premium tumbled to 37 lakh, kids’ fell to 14 lakh and the standard ones too dipped to 65 lakh. Premium and kids’ cycles still made up 40 percent of the overall market. The inflection point came in FY21. The share of premium and kids’ cycles jumped to 50 percent, and in FY22, it inched to 52 percent. This meant boom time for Ninety One.

Chopra stresses that consumers gave Ninety One a chance because it stood out with distinguishing features. Take, for instance, the move to come up with sealed bearings. The idea is to protect against monsoon, water and dust, resulting in an effortless pedalling experience. Then alloy crank with lightweight material and higher load bearing capacity reduced bike weight by up to 5 percent. Disc brakes with customised ceramic brake pads increases the lifetime of the brake pads by 30 percent. Ninety One also rolled out India’s first Magnesium bike. Magnesium as a material, explains Chopra, is not only lighter in weight, but is also moulded rather than welded, which allows for striking frame designs. “That’s the level of engineering we have done," he says. “We have designed each and every component bottom-up."

Though meticulously designed and executed, Ninety One too had its low moments. Chopra dabbled in the toys business for a few years and later shut it when he realised there was no differentiation and the business was fast turning into a ‘trade’ rather than a ‘brand’. The learning was incorporated. The plan now is not to let the foot off the innovation pedal, and make Ninety One a name to reckon with on the global arena.

For somebody who spent over a decade in the US, and still didn’t go for US citizenship, the move to come back to India has to have more than what meets the eye. Chopra smiles. “I didn’t want to give up the opportunity of becoming India’s prime minister," he smiles.

When Bharadwaj of A91 Partners asked the same question and got a similar response, he too smiled. The reason, though, was different. “This makes it the two of us," Bharadwaj laughs.

First Published: Apr 18, 2022, 15:51

Subscribe Now