The Patels, argued the second-generation entrepreneur, needed to seriously look into the business of floor tiles, which was in the midst of an explosive growth and was a much bigger market. For the family, though, betting big on floor tiles meant entering into an unchartered territory. The risk, many well-wishers and traders in the market sounded a word of caution, was likely to outweigh the rewards. Everyone advised taking baby steps and hedging bets.

Bhavesh, however, didn’t believe in taking half measures. “There is no such thing as calculated risk," recalls the 43-year-old. He managed to convince the family, left for Germany in 2000 to explore options and gain technical know-how to make ceramic floor tiles, and came back after seven months with some new technology and second-hand equipment. There was palpable excitement, as the plant started the production of ceramic floor tiles from 2001. The Patels were confident of capturing a decent market share.

After six months, the writing was again on the wall. There was negligible uptick, the tiles were getting rejected, and everybody in the family was shocked. Though the tiles were differentiated in style and quality, there were no takers. The market, Bhavesh realised, was addicted to the style of tiles made by Spartek, one of the earliest makers of floor tiles.

Buoyed by his success, Bhavesh planned an audacious move. A year later, he rolled out India’s biggest vitrified tiles. The idea was not only to continuously manufacture innovative products but also to ‘excite’ the highly cluttered market that had scores of local players importing from China and playing price warriors. The move, unfortunately, bombed. In two years, he stopped making these tiles. The flop show was more to do with logistics rather than quality. First, the big size meant little room for traders and retailers to display the product. Second, it made transportation cumbersome. Third, since it was a first-of-its-kind in India, builders were hesitant in embracing the new product.

![]()

Though the failure proved costly, Bhavesh continued with his risky bets. In 2009, he went to Italy with his brothers to secure supplies. During one of the factory visits, he was shown a digital printing machine. The technology was not only missing in India, but was also absent in countries like China. Bhavesh sniffed a massive opportunity. “Risk lena tha aur kuch different karna tha (I wanted to take a risk and do something different)," he recounts.

There was one problem, though. The machine was prohibitively priced at `5.5 crore. The cost, in fact, was not the only snag. Back home in Morbi, Gujarat, the Patels were all set to inaugurate a new plant. Getting a digital printer would not only upset all the plans, but also delay manufacturing. The machine, the Italian makers underlined, would take at least 21 days to be transported, and then a few weeks to assemble and roll out production.

Bhavesh, though, was in a tearing hurry. He airlifted the machines, got an Italian technician who took just 10 days to set up the plant, and the tiles were ready to be shipped to market. Bhavesh knew a failure this time would make things difficult for him as there was too much at stake. “I was mentally prepared for the worst," he recalls, adding that the family was also briefed to look at the hefty amount as a long-term investment rather than perceiving it as a magic wand. For all these years, Bhavesh had invested in technology and innovative products. “I was okay with either 0 or 100," he underlines.

The bet paid off handsomely. Over the next four years, revenues jumped to Rs 270 crore.

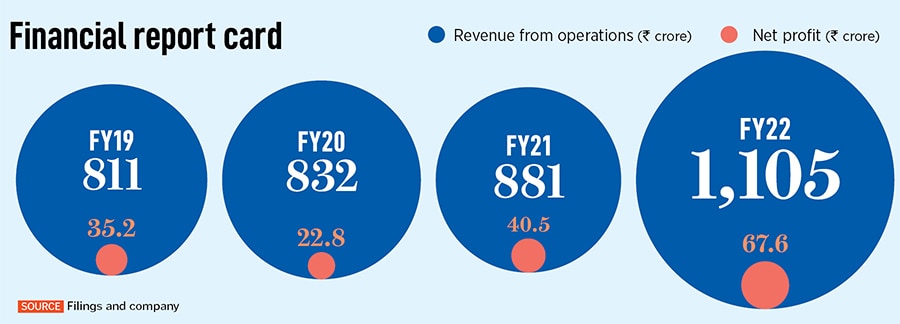

Since then, there was no looking back. From `811 crore in operating revenue in FY19, Varmora closed FY22 at Rs 1,105 crore. Net profit during the same period increased from Rs 35.2 crore to Rs 67.6 crore. The Morbi-based company is among the top five tiles and bathware makers in India, and has nine manufacturing units in Gujarat. It is available across 5,000 retail outlets, has 700 dealers, 12 branch offices and 325 exclusive showrooms in India, and 15 across the world. It also exports to over 74 countries, and in June, private equity major Carlyle bought a minority stake in the company.

![]()

For Carlyle, a ‘significant minority stake’ in the company—sources inform that Varmora diluted a little over 30 percent for a $100-million investment—comes on the back of rapid progress made by the brand.

“We are impressed by the brand salience and consumer pull," underlines Amit Jain, managing director and co-head at Carlyle India Advisors. He points out three factors behind an impressive strike rate: A differentiated product portfolio, strong pan-India distribution network and an exceptional management team.

The move to diversify the company into multiple categories also aided fast expansion. “A diversified product portfolio, healthy capacity utilisation levels and strong brand image have helped the company," credit ratings agency CARE underlines in its latest report.

During the last two years, the group focussed on expanding its presence in the value-added large-size tiles. “With various marketing and branding initiatives, the group has been able to develop a strong brand," notes the CARE report.

Bhavesh, meanwhile, shares an untold brand and personal story. Back in 2004, he decided to focus his attention on marketing and branding activities. The first big move was to bring all tiles under one brand. So he reached out to a branding agency in Gujarat, which suggested a radical move. “Can you change your surname?" the agency owner asked.

“When Benz can be a powerful name in Mercedes-Benz, then why not Varmora?" he argued, alluding to going back to the original surname Varmora. “The name also has an Italian zing, which can be a big edge in this industry," he continued to impress upon Bhavesh, who was warming up to the idea.

After much persuasion, the family agreed. Bhavesh Patel became Bhavesh Varmora, and the brand Varmora Granito was rolled out in 2005.

![]()

The second big move was to build the brand. Till then, the company had grown on the back of its quality, and push factor induced by retailers and dealers who were offered a fat margin. To play a branded game in a huge unorganised industry of tiles and bathware, Varmora needed a pull. Bhavesh poached top guys from rival Kajaria at hefty packages, beefed up the sales and marketing teams, and rolled out BTL (below the line) and ATL (above the line) advertising. The retail counters were decked up with Varmora branding, and advertisements were run in theatres across smaller towns and cities.

The results are visible after one-and-a-half years of consistent marketing and branding labour. “We are among the top five players in the country," claims Bhavesh. Even if in the Rs 70,000-crore branded market of tiles and bathware, he underlines, Varmora is able to bag a neat 10 percent, it would be a satisfying achievement. “With Carlyle, we have entered our first phase of growth," he says, underlining that the bootstrapped and profitable company never felt the need to tap the public market. “One has to be very clear about why one needs an IPO. Is it for capital or ego or some badge of honour?" he asks.

Varmora, he points out, never needed capital. So tapping public market was out of question. What the company badly wanted was a long-term and committed PE partner who could bring in systems, processes and structure for the next phase of growth. “IPO will happen after two to three years," he says.

![]()

Varmora, though, needs to aggressively step on the branding and marketing pedal for its next phase of growth. Like Mercedes-Benz, the tile maker has to become aspirational if it has to become the darling of the masses. Low-entry barriers, easy availability of raw material and limited initial capital investment requirement have attracted a large influx of regional and unorganised players in the segment, CARE points out as some of the threats for the brand in its report. Can Bhavesh build brand stickiness and high recall?

The entrepreneur, for his part, reckons that the brand has all that it takes to create a long-lasting institution. Varmora’s biggest strength, he stresses, is the bonding among the family members. “The family that sticks together can make anything possible," he smiles.