How Jyothy Laboratories Silenced Sceptics

The homegrown consumer goods company has beaten the odds and transformed to turn around the Henkel India business

Soon after homegrown Jyothy Laboratories acquired Henkel’s India business in May 2011, joint managing director Ullas Kamath went on a month-long road trip across the country. Kamath remembers that as being a lonely time, with only his driver for company. Just as well, though, as it was also a time for introspection and ideation.

Consider that Kamath, along with his boss MP Ramachandran, the chairman-promoter of Jyothy, had just engineered a takeover that left many in the industry stunned. For a bargain basement price of Rs 685 crore, Henkel AG had sold its Indian consumer products business to Jyothy, which hadn’t yet completed three decades of operations.

No one doubted that Jyothy had come a long way since it was founded in 1983. However, it was still considered a one-hit wonder with Ujala, its fabric whitener, as the cash cow. The markets feared that Jyothy had bitten off more than it could chew. How could a domestic company successfully revive an ailing multinational that had accumulated losses of around Rs 600 crore? Did they have the management bandwidth or the marketing budgets? What about the R&D set up that would spur innovation—a key factor in the success of consumer franchises?

In the months that followed, the doubts manifested in Jyothy’s stock price which took a beating, erasing almost 40 percent of its market cap. The sceptics were vindicated—but not for long.

Not one to be fazed by the noise around him, Kamath, who had been keeping a close eye on Henkel, had an integration plan all laid out in his head. But to begin with, he knew that rallying the sales force (known internally in the company as its ‘white army’) was what would eventually make the difference between success and failure. On that journey, Kamath crisscrossed the country, making it a point to spend the nights in the homes of his salespersons. “I wanted them to feel like they were the most important people in the company,” he says.

Two-and-a-half years on, his efforts have borne fruit. Jyothy is on course to cross Rs 1,000 crore in revenue. Its EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation) margins—a key measure of a consumer goods company’s health—are at 14.5 percent, up from 9 percent. It has also charted out an aggressive growth path. So much so that Ramachandran and Kamath are already mapping out the road ahead. Their destination: Rs 5,000 crore in sales in the next five years.

Integrating Henkel

When Jyothy inked the Henkel deal in May 2011, here’s what it bought: The Indian subsidiary of a German multinational that had been operating in India for the last 22 years. During that time it had never been profitable and, with a top line of Rs 400 crore, its losses stood at Rs 40 crore a year. Over the years, it had lost over Rs 600 crore, a sorry legacy for a prospective buyer to have to take over. Its brands, Henko (detergent), Pril (utensil cleaner) and Margo (soap), were seen as laggards and had never been backed up with significant marketing spends.

But for Kamath all that mattered was the gross margin. And all of Henkel’s brands had gross margins of over 25 percent. Some like Margo, a small soap brand with a fanatical following, exceeded 50 percent. A state-of-the-art detergent plant in Karaikal near Pondicherry was part of the deal too. Henkel’s accumulated losses of Rs 600 crore were also transferred to Jyothy’s books.

This, however, was not a worry for Kamath. Jyothy, which had followed a dispersed manufacturing model, had 22 plants across the country. While setting these up, the company had been granted tax breaks that would expire over the next few years.

Kamath could set off the Rs 600 crore against this tax liability. The company also had real estate worth at least Rs 100 crore. Further, from Henkel’s staff strength of 475 people, Kamath believed he would need to retain no more than 50.

“This was the time when Paras had been sold for eight times its sales [to Reckitt Benckiser]. And here I was buying a company for one-and-a-half times its sales value… no one was convinced,” says Kamath.

Particularly the investor community. Sure, consumer stocks were on fire and other homegrown peers such as Dabur had also made acquisitions, but here was a company buying a business two-thirds its size! There were doubts on whether the two distinct and disparate cultures could be seamlessly integrated. To boot, detergents remain a very crowded category and P&G and Hindustan Unilever, which together control 52 percent of the market, have not hesitated in fighting bruising detergent wars. Did Henko stand a chance? And lastly, there was the debt overhang for the Rs 685 crore that Jyothy had borrowed for the acquisition. By the end of 2011, the stock was quoting at Rs 77, down from Rs 105 when the deal was announced.

“I wasn’t perturbed one bit. I started this business with just Rs 5,000,” says Ramachandran. This is hardly bluster from a man who lived in a 285-sq-ft house till 1998 so that he could plough back all his earnings into the business. He, however, knew that the company he founded (and still owns 66 percent of) would have to shake things up in order to weather this transition.

Transforming Jyothy

For the first year after acquiring Henkel, Kamath, a Jyothy lifer, says he focussed mostly on maintaining status quo. Henkel’s sales stayed at about Rs 400 crore while Kamath went around the country rationalising costs. Then change started filtering through. The office in Chennai was shut down. Henkel employees who did not want to work for an Indian company left and other overheads were reduced too.

But that would have to change. Decisions would have to be taken based on data and hard facts. And driving this transformation would be new CEO S Raghunandan, an acknowledged turnaround expert. The unassuming 5-feet-8 South Indian had been blooded at Asian Paints and Hindustan Lever subsequently, he’d gone on to set up Dabur’s international operations from Dubai and then, to grow Paras’s business till it was sold to Reckitt Benkiser. Raghu, as he is known in the industry, had left Paras post the takeover, as he saw that job as a “holding operation”.

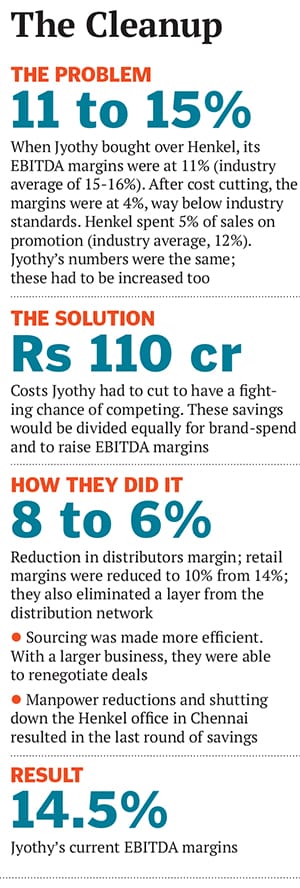

He says he accepted the Jyothy assignment because of the challenge it presented. To begin with, Jyothy’s erstwhile businesses had a margin profile of 11 percent versus the industry average of 14-15 percent. Add to that, both Henkel and Jyothy had below average spends on advertising. “Henkel failed due to high overheads and low brand investments,” says Raghu. But Jyothy, which had had a CAGR (compound annual growth rate) in single digits in the last five years, had also failed to invest. So Raghu saw his job as two-fold: Nurse Henkel brands to health and integrate the cultures of two very disparate organisations.

But first Raghu needed to find money to invest. Within three weeks of joining, he told Ramachandran and Kamath that costs had to be cut by Rs 110 crore. Of this, Rs 55 crore would be spent on advertising and the rest would be added to the bottom line—without that, growing the company would be impossible. By all accounts, both were taken aback but decided to back Raghu’s strategy.

“This is what made it possible for us to back Jyothy’s turnaround effort. We saw that not only did they understand they needed to change the business and bring in professional managers but they also gave him the freedom he needed,” says Sashikanth Balachandar, director - listed equities at Premji Invest, which manages funds for technology billionaire Azim Premji. Premji Invest holds around 3 percent stake in the company.

Apart from streamlining costs, another critical step was to rework its list of distributors. Jyothy had been operating with smaller players who had the experience to sell its products, with Ujala being the most important. Now with a stable of Henkel’s products on hand, it started tapping large distributors. “Outside of those who served multinationals, our criterion was that they should be among the top five,” says Kamath. This helped strengthen their reach.

Raghu also wanted to add a layer of zonal sales managers. When Kamath handled the business, each state sales manager had reported to him directly. Raghu believed there needed to be one more layer to provide leadership and strategy on the field. It was here that the relationship between Kamath and Raghu played a key role. Ordinarily, there would have been a conflict, as Kamath had nurtured many of these state sales managers. But he stepped aside and gave Raghu a chance to make changes. “It was a painful period for me as many left, but I made sure I did not interfere in the new structure,” says Kamath. The CEO was in charge: That was the signal sent down the rank and file.

Once these savings were in place, Jyothy was able to spend 10 percent of its sales target on brand promotion. While Raghu doesn’t say how much the company gained in bargaining power with media buying agencies, he does point out that they were able to get more air time relative to the money they put in. In a significant departure, the company chose to work with multiple advertising agencies. It had so far only worked with Anjan Chatterjee, founder of Situations Advertising (also the man behind the Oh! Calcutta and Mainland China restaurant chains), who had almost single-handedly built the Ujala brand for the company.

What Next?

At present, Jyothy finds itself in a comfortable position. In December, Kamath, who says he now looks after all things related to the balance sheet, paid back the Rs 685 crore that was borrowed to buy Henkel India. He raised Rs 400 crore at zero coupon payable at the end of three years—that is, there were no interest payments in the interim. Another Rs 300 crore was brought in by the promoters in the form of preferential equity at Rs 175 a share. As a result, the company now has Rs 175 crore lying in the bank. “I did this [quick pay-off] to give Raghu enough flexibility to spend on the brands,” says Kamath.

But the financial planning is not over by a long shot. Jyothy now has to look at repaying the Rs 400 crore it raised—Kamath has till March 2016 to do it. And this is where Henkel comes in. At the time of the sale, Jyothy had offered Henkel the option to take a 26 percent stake in the company. Kamath believes this could be achieved at a 50 percent premium to the prevailing market price. The money raised should easily pay back that loan.

For now, Kamath says he’s charted out a path that takes Jyothy from Rs 1,000 crore to Rs 3,000 crore in revenues. This will come mainly through growth in India. The next step is to touch Rs 5,000 crore and for that they will have to look overseas.

Kamath’s initial targets are the Middle East and North Africa where the company can work with distributors of Indian products. Southeast Asia is another focus region. This geographical expansion is relatively low on risk given that it is a time-tested model that homespun Indian consumer good companies such as Dabur, Marico and Godrej Consumer Products have used over the years.

Then there is vision 2020: Rs 10,000 crore. This, Kamath says, will need a strong global partner to enable a stronger bench of products that can be launched quickly. “Maybe Henkel can broaden and deepen its partnership with us as we go forward,” says Kamath. After all, they do have the products that can be worked on jointly—already Henkel is a permanent invitee to Jyothy’s board meetings.

These are ambitious plans, indeed, but the Ramachandran-Kamath duo has battled several odds to reach this point. So while Rs 10,000 crore may sound fanciful, their track record doesn’t make it sound improbable.

First Published: Apr 14, 2014, 07:44

Subscribe Now