Accel India: Sharpening investment instincts

Spotting an opportunity early, making follow-on investment rounds, and guiding it to unicorn status is an art few peers would have mastered as well as Accel has

[br]In May, Fred Destin, a former general partner (GP) at Accel and now founder of a £100 million seed-stage fund Stride.VC, put out a seemingly innocuous question on Twitter. “If you could make the ‘venture capital product’ a better experience for founders, what you change?” Destin got over 150 replies, enough for him to convert the thread into a piece on Medium.com.

The answers were illuminating, if not unpredictable: Give pitchers faster and honest rejections have transparent valuation criteria and more clarity on the evaluation and investment process and do something about the excessive homogeneity among the VC community, among several others. Tied in with the problem of homogeneity is the lack of GPs with operational experience. One response to Destin attempted to nail it: “You cannot become a GP at a VC until you have founded, operated and exited a business at a multiple of three times the fund size or capital you aim to raise (or have failed as an entrepreneur more than twice). Another reply from Europe summed it up well, too: “We don’t have enough GPs that have built and run early-stage companies with expertise in product, software delivery, sales/distribution.”

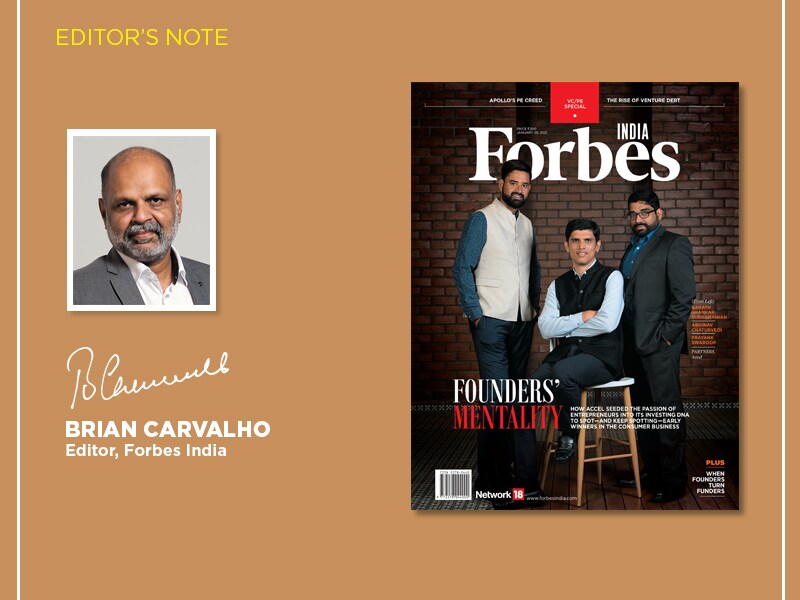

And that brings us to the VC firm that graces the cover of Forbes India this fortnight in our annual VC/private equity (PE) special. The Palo Alto-headquartered VC firm Accel entered India in 2008 after acquiring a domestic early-stage fund, along with its four founders, two of whom were entrepreneurs themselves before switching to the other side. Subrata Mitra, for instance, was a managing director of the India operations of Tavant Technologies, a digital products and platforms company he had also founded Firewhite, a developer of automatic systems for handheld devices, which Ubiquio acquired in the early 2000s. Prashanth Prakash had founded IT services firm NetKraft he exited in 2004.

It’s those stints and the robust operating experience they provided that would have played a part in sharpening Accel India’s investing instincts. Spotting an opportunity early, making follow-on investment rounds, and guiding it to unicorn status is an art few peers would have mastered as well as Accel has. Consider the bets that went on to be worth over $1 billion: Myntra, Flipkart, Ola, Swiggy, Freshworks, and the latest in the pack, Zenoti. In the process, the firm has done well to spot sectoral trends before others in less-fashionable sectors such software as a service, agritech and B2B. The firm is cognisant of the reality that not every idea it touches will blossom into a billion-dollar Lily of the Valley, but as Mitra tells Rajiv Singh, who penned the cover story: “You need to find enough winners to far outweigh the losses.”

For more on the ‘Founders’ Mentality’, Read our cover story.

From capital to fuel startups, let’s move to the other pool of PE, which involves buying into mature companies with growth potential, and possibly in distress. One firm with a focus on stressed assets is the US-headquartered alternate asset manager Apollo Global Management, which started as a joint venture in India with ICICI Ventures in 2011 before going solo last April. That may have been around the time, as Pooja Sarkar, who dug deep into Apollo’s India blueprint, writes, that Apollo’s first investment in a floundering asset—and the first company of the 12 referred to the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code in mid-2017 for resolution—was beginning to turn around. Sarkar analyses how Apollo deals with the complexities of fixing assets that go horribly awry.

Best,

Brian Carvalho

Editor, Forbes India

Email:Brian.Carvalho@nw18.com

Twitter id:@Brianc_Ed

First Published: Jan 18, 2021, 09:33

Subscribe Now