Adar Poonawalla's vaccine: No shot in the dark

Poonawalla is betting big on a Covid-19 vaccine, and preparing for the next possible pandemic

Adar Poonawalla inside a vaccine-making unit at the Serum Institute where the experimental Covid-19 vaccine will be manufactured

Adar Poonawalla inside a vaccine-making unit at the Serum Institute where the experimental Covid-19 vaccine will be manufactured

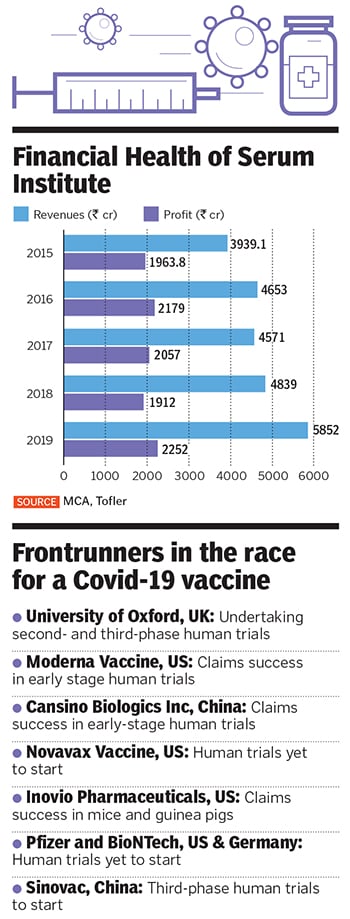

Image: Avinash GowarikerAdar Poonawalla has much to thank god for, especially during these trying times. Of course, the 39-year-old runs the world’s largest vaccine manufacturer and is heir to the fortunes of his billionaire father, Cyrus Poonawalla, the 165th richest man in the world with personal wealth in excess of $10.9 billion, according to Forbes. Yet, it is a decision to walk away from selling a stake in his company, the Serum Institute of India, sometime in 2015 that he is grateful for.

Five years ago, the privately owned maker of vaccines was contemplating a 10 percent stake sale to private equity (PE) firms and sovereign funds at a staggering valuation of ₹80,000 crore. The deal would have been India’s largest PE investment, and came close on the heels of merger talks with homegrown pharmaceutical giant Cipla.

“We had looked at a stake sale because people said, you’ve got so much value in your company, why don’t you unlock a little bit of that and use it to acquire technologies or other companies,” says Poonawalla. “But some of the larger acquisitions we were looking for, worth between $1 billion and $2 billion, didn’t go through. We then said forget it. Thank god for that.”

Not selling the stake to a PE fund, which would have eventually forced the Poonawallas to go public, is now proving to be a blessing amid the Covid-19 pandemic, when Poonawalla is betting against all odds on an unproven vaccine that could potentially stem the spread of the coronavirus. The vaccine, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, being developed by the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford, is a frontrunner among about a hundred others that are being developed around the world.

“It’s a huge personal risk I am taking,” Poonawalla says. “But it’s a risk I can take because we aren’t a listed company. If we were a listed company, I would have to be accountable to shareholders, investors, and bankers.” By mid-June, Pune-based Serum Institute will begin manufacturing the experimental vaccine, having put on the backburner another project to produce monoclonal antibodies. That opportunity, Poonawalla reckons, could cost him millions of dollars. “I am afraid to even calculate that figure so I can live in self-denial of the many millions of dollars that I may have lost,” he says. “But again, I’m only accountable to myself.”

For now, his bet seems to be on track, barring minor hiccups. Scientists developing the Oxford vaccine have claimed an 80 percent potential for success, having already proven in trials that the inoculations were harmless to humans. The vaccine uses a weakened version of chimpanzee adenovirus as a vector, infused with the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, and is currently in advanced human trials involving some 10,000 people. The US government has agreed to pay $1 billion to buy 400 million doses from AstraZeneca, the British pharmaceutical giant, tasked with the distribution. “We should be able to make about 4 to 5 million doses per month,” Poonawalla says. And scale it up to about 400 million doses a month.”

Fighting Covid-19

Serum Institute will not be producing all of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine doses across the world, but will have exclusive manufacturing rights for the Indian market, with a population of over 1.2 billion people, in addition to a few low-income countries. “We are the only ones who have the capability, so perhaps you can say it is exclusive,” Poonawalla says.

Right now, Serum Institute is firming up a deal with Cambridge-headquartered AstraZeneca, who would develop, globally manufacture and distribute the vaccine developed by the Jenner Institute and Oxford Vaccine Group. AstraZeneca was brought in by the UK government for its expertise in late-stage drug trials, financial resources, and global distribution. “We can’t comment on the ongoing deal with AstraZeneca,” says Poonawalla. “We have an excellent relationship with them and we’re working out its terms.”

But even before AstraZeneca was drafted in, Poonawalla had begun talks with the Jenner Institute, with which it was already developing a malaria vaccine. “As we approached them, Dr Adrian Hill and his team were very receptive and said Serum Institute would be one of the four or five companies they would give it to in the world to manufacture,” Poonawalla says. “I decided to sacrifice one of my existing facilities, which makes some very lucrative vaccines, because we don’t have a dedicated readymade facility for this.” He has now set a target of stockpiling the vaccine by November, when the clinical trial in the UK is likely to be over. So far, the first phase of the trial has been completed, with the researchers recruiting volunteers for the second- and third-stage trials.

There is good merit in that gamble, reckons Anurag Rathore, a professor at the Department of Chemical Engineering at Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi and scientific advisor to numerous biotechnology companies. “Historically, companies that were the first to bring out a medicine have always had an advantage, even if a second drug was of better quality,” he says. “The challenge is to capitalise on the gains, and that means manufacturing at risk to start selling the drugs as and when the trials are over. In that sense, Serum Institute’s call is a commercial decision, a bet that is like any other, which could go either way.”

Arokiaswamy Velumani, chairman and managing director of Thyrocare Technologies, one of India’s largest private testing laboratories, says the expectation from Serum Institute is high. “At this moment, we can simply hope that Serum Institute can deliver, and we are eagerly looking for an escape from the situation,” he says. “They have built up a good reputation for manufacturing affordable vaccines across India and Africa.”

Serum Institute’s deal with AstraZeneca is likely to involve an upfront payment, based on the doses or the requirements from India. In return, it could charge ₹1,000 per dose when the vaccine goes on sale. For now, Poonawalla says, the government of India as well as of Maharashtra are his priority, before looking at the export market. “I will leave it to the government to decide on who to vaccinate first,” Poonawalla says, while also admitting that he expects the government to purchase the vaccines for mass inoculation. “We are not asking for any money for dedicating a ₹700-crore manufacturing plant, including the manpower, energy cost, and other things from the government. All we are saying is buy the vaccine and give it free to everyone so that no citizen of India has to pay for a Covid-19 vaccine. The government can withdraw the money from the defence budget.”

India has over 1.9 lakh Covid-19 cases, with over 5,000 deaths (as of June 1), and the country has only begun to restart its economy after a two-month lockdown. There had been concerns over the high cost of Covid-19 testing, forcing the Supreme Court had capped costs at ₹4,500. Recently, though, with the availability of locally-made kits, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR)has removed the ceiling, asking the states to negotiate and fix it. “The vaccine should be costing twice the testing price, and I had been advised to price my vaccine between ₹5,000 and ₹6,000,” Poonawalla says. “But in India, I took a philanthropic call.” Besides Covid, Poonawalla is setting up a $300 million pandemic-level manufacturing facilityTaking after his father

Besides Covid, Poonawalla is setting up a $300 million pandemic-level manufacturing facilityTaking after his father

Taking philanthropic calls isn’t new to the Poonawallas.

Over decades, they have built their business empire on the back of low-cost vaccines, which helped it penetrate the export market without large-scale promotions or advertisements. Much of that credit also goes to father Cyrus, who began building the vaccine business with an investment of ₹5 lakh, when he set up a small laboratory at the family’s stud farm in 1967.

Back then, the farm’s retired horses were donated to the government-owned Haffkine Institute in Mumbai, which made vaccines from horse serum. With vaccines in severe shortage and imported at high prices, especially since India was a fledgling democracy, Cyrus knew the potential was massive. By 1974, Serum Institute introduced the DTP (diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis)vaccine for children, followed by a serum for snakebites in 1981 in 1989 it began producing M-Vac, a measles vaccine, and within a year became the country’s largest vaccine manufacturer. “In the 1990s, the company got accreditation and approval from the WHO,” says Poonawalla. “That meant we could export our products and sell in other countries. That was the real turning point.”

Since then, the company has built a reputation as the world’s largest vaccine maker. By the time Poonawalla Jr joined in 2001, Serum Institute’s business had expanded to some 50 countries. “I loved the idea of expanding overseas because it was so easy to sell it to them instead of government orders here in India,” he says.

In 2012, Serum Institute bought Dutch vaccine maker Bilthoven Biologicals, thus acquiring the technology for making injectable polio vaccines, which was then available with just three producers globally. That was followed by the acquisition of the Czech arm of US-based firm Nanotherapeutics for nearly ₹500 crore to help increase the production capacity of polio vaccines to more than 200 million doses by 2020, making Serum Institute the world’s largest maker of injectable polio vaccines.

“We’re in 165 countries globally now. Until the Narendra Modi government came to power and started buying a lot of vaccines, exports contributed 85 percent of our total sales. Now it’s about 60 percent exports and 40 percent local sales,” says Poonawalla. In the process, at least 65 percent of all children globally have received a Serum Institute vaccine once, according to the company, and it sells 1.3 billion vaccine doses annually.This year, the company is also looking to launch a cure for dengue, in addition to a vaccine for malaria.  Preparing for pandemics

Preparing for pandemics

Even as he begins manufacturing the Oxford vaccine while awaiting the efficacy results, Poonawalla has tied up with a few other partners in the US and Europe to develop similar coronavirus vaccines.“We are working with multiple partners across the US, UK, and Europe on four different vaccine candidates,” he says. “These include Codagenix, Themis, and the remaining two we can’t talk about at this stage. We never assumed that only one vaccine candidate would work. Vaccine production is like a rollercoaster ride with many probable results you need to be patient.”

Serum Institute’s deal with the US-based Codagenix, a clinical-stage biotechnology company, involves rapidly co-developing a live-attenuated vaccine against the coronavirus. A live-attenuated vaccine can mount an immune response to multiple antigens of the virus and can be scaled up for mass production. “Their technology is to reverse engineer and remove the harmful properties of a virus whilst keeping the antigens,” Poonawalla says. With Austria’s Themis, work is underway to develop a vaccine by modifying a measles virus vector to carry coronavirus antigens. “These two would be products where we’re co-developing, scaling it up, and doing the trials ourselves.”

Working with multiple partners to develop numerous vaccine candidates has other long-term benefits: Even if one among the hundred global candidates is successful, Serum Institute and its partners could manufacture variants, perhaps even better ones. “With these live-attenuated vaccines, they offer good long-term immunity,” says Poonawalla. “Even if we are out with a vaccine two years later, the Covid-19 crisis is going to go on for at least five years or even a decade. Governments will want to vaccinate their whole population, and stockpile.”

Alongside, he is setting up a “pandemic-level manufacturing facility” over the next two years,worth $300 million, to produce billions of vaccine doses. Much of that also has to do with Poonawalla’s firm belief that the world will likely see another pandemic in the next few decades. “That pandemic could be even worse and deadlier than Covid-19,” he says. “The only lesson we have learned from this epidemic is how underprepared we were in manufacturing, in our health systems, detection, and testing. The facility we are planning will be the first of its kind in the world.”

“Chances of a pandemic over the next 10 years is pretty high,” says Rathore of IIT Delhi. “The fundamental reason for that is because humans are encroaching more and more into forests and other areas where newer pathogens are finding their way up.”

Meanwhile, in April, the Serum Institute struck a deal with Pune-based Mylab Discovery Solutions, the first Indian company whose testing kit for Covid-19 was approved by the ICMR. “We kept thinking about what we could do to help open up the economy, because a vaccine may or may not come even after a year,” says Poonawalla. “That’s when a friend asked if I could invest and partner with them to scale things up.” That deal too, Poonawalla reckons, has serious long-term gains, particularly since testing kits could go a long way in helping prevent diseases.Since the deal was announced, Poonawalla says, Mylab has been able to ramp up production to over 20 lakh testing kits a week from 3 lakh.

The road ahead

With four Covid-19 vaccine deals, in addition to a plethora of other vaccines, and foray into testing kits and newer areas, Poonawalla has his hands full. “I don’t imagine myself expanding in a major way, or diversifying in anything else,” he says.

Over the next few months, Poonawalla also sees some churn in vaccine costs. “Going forward, with the extremely high GMP [good manufacturing practice] costs and regulations, we may have to slowly start increasing prices of vaccines.” To mitigate the price rise, he expects governments to allocate more money towards the healthcare, rather than on defence or space programmes.

Then there are the millions Poonawalla stands to lose if his gamble on the Oxford vaccine fails. Questions are already being raised after the virus remained in the upper respiratory tract of monkeys exposed to it. “We should refrain from jumping to conclusions as the studies are still inconclusive,” Poonawalla says. Animal studies are often indeterminate and ultimately its human studies that matter.“We have already shown safety to humans and are waiting for the efficacy studies, which will take a couple of months.”

Adds Poonawalla: “Vaccines aren’t recognised or spoken about like automobiles or the consumer sector. But, people have now realised how critical vaccine manufacturing and research is to humanity, because you need people to be alive in order to buy a mobile phone or a carpet or a chair.”

First Published: Jun 04, 2020, 13:14

Subscribe Now