Meet the Kolkata family behind the world's finest teas

The Luxmi Group, owned by the Chatterjees of Kolkata, has been making some of the world's most coveted teas for over 100 years, with businesses in fine carpets and furniture as well

Dipankar Chatterjee (left) and son Rudra Chatterjee run the Luxmi Group from Kolkata

Dipankar Chatterjee (left) and son Rudra Chatterjee run the Luxmi Group from Kolkata

Image: Debarshi Sarkar for Forbes India[br]Tea has been done a great disservice by being called a commodity,” says Rudra Chatterjee, managing director of Kolkata-based Luxmi Group. “When you buy wine or olive oil, you see the name of the grower or producer on the bottle but when you buy tea, you see the name of the distribution company, not the producer. This is something we want to change.”

Forty-three-year-old Chatterjee is the third generation of the family to be part of the Luxmi Group. The company was started by his grandfather PC Chatterjee, in 1912, as an act of defiance against British colonial rule, with the aim to make tea a tool in the Satyagraha movement. On a tract of land that he owned in Pearacherra, in the Unakoti district of northern Tripura, he started producing tea independently at a time the industry in India was dominated by the British. But what started out as an act of defiance soon turned into a practice of growing superior quality tea, as produce from Chatterjee’s estate began to fetch the best prices at the Calcutta auctions.

“Tea is an industry that requires a planter’s mindset it is different from finance or banking,” says Dipankar Chatterjee, chairman of Luxmi Group, and Rudra’s father. “You require knowledge of both the people and the environment, and you require time. Tea doesn’t grow immediately it needs nurturing and tending over years.”Staying true to this approach, the Luxmi Group has expanded to include 25 estates, produce 30 million kg of tea every year, and employ a workforce of 30,000 people. It also found its way to the British Queen when Prime Minister Narendra Modi gifted her Silver Tips Imperial tea from the Makaibari estates in West Bengal during his state visit to the UK in 2015.

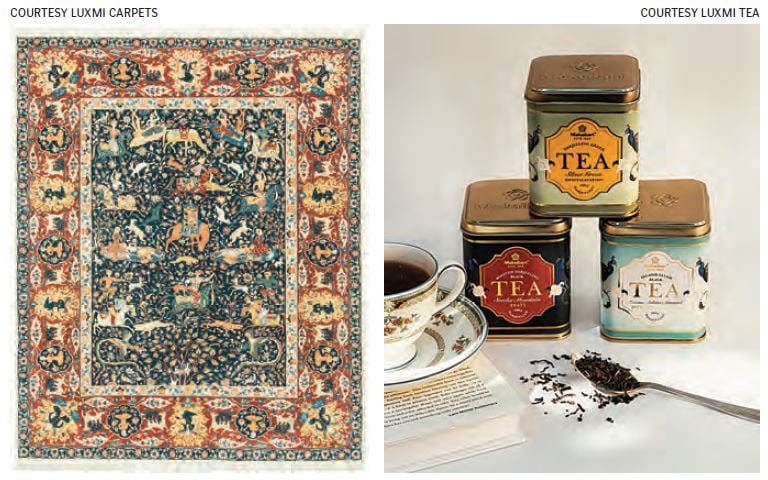

Along the way, the group has grown from being a tea-producer to becoming a world leader in hand-woven carpets, and, more recently, the maker of fine wooden furniture. In 1998, Dipankar acquired Obeetee, “which was a well-run business that Edward Oakley used to manage”, and which now employs over 30,000 carpet weavers from 900 villages in and around Uttar Pradesh’s Mirzapur district. In 2015, Rudra started Manor & Mews, which creates a range of bespoke and traditional styles of furniture with a modern twist, with its atelier in London and manufacturing units in Europe and Jaipur.

Commenting on managing a tea and carpet business that are so different from each other, Rudra says: “It’s like having two children, who are very different from each other… Both businesses are solid, ethical, innovative and beautiful. They have a huge impact on people. But you also enjoy the differences, such as managing the different challenges that each presents.”

Buying the best

“Something that my father believes in, and I agree with, is that if we acquire tea gardens then we should go for the best properties,” says Rudra. This has been the guiding principle when Luxmi Tea acquired estates in Assam. “The Moran district in Assam is the best tea-producing region in the state, and today we have six estates there. If we didn’t buy estates for many years in the middle, it was because there weren’t any good properties coming up for sale. When some of the best properties became available, we bought them.” Moran is home to the famous Halmari estates, which produce CTC teas that have won the Global Tea Championship Award back-to-back, from 2015 to 2019. The Luxmi Group sells hand-made carpets through Obeetee produces 30 million kg of tea every year[br]It was this quest for the best estates that led to Luxmi Tea acquiring the famed Makaibari Estates of northern Bengal in 2014. Under family ownership since 1859, the 677-hectare estate is said to produce the finest of Darjeeling’s aromatic brews. In the 1970s, the estate began to implement biodynamic principles of farming, with owner Swaraj (Raja) K Banerjee letting two-thirds of the estate become a sub-tropical forest, which greatly improved the health of the soil, rejuvenated wildlife and the lives of locals. Makaibari’s Silver Tips Imperial tea is sold by premium vendors, such as England’s Hampstead Tea, for $40 for 100 grams.

The Luxmi Group sells hand-made carpets through Obeetee produces 30 million kg of tea every year[br]It was this quest for the best estates that led to Luxmi Tea acquiring the famed Makaibari Estates of northern Bengal in 2014. Under family ownership since 1859, the 677-hectare estate is said to produce the finest of Darjeeling’s aromatic brews. In the 1970s, the estate began to implement biodynamic principles of farming, with owner Swaraj (Raja) K Banerjee letting two-thirds of the estate become a sub-tropical forest, which greatly improved the health of the soil, rejuvenated wildlife and the lives of locals. Makaibari’s Silver Tips Imperial tea is sold by premium vendors, such as England’s Hampstead Tea, for $40 for 100 grams.

“There is no greater tea estate in Darjeeling than Makaibari it is the last word among teas, whether in Japan, or England, royal houses,” says Rudra. “It is also the choice of tea Satyajit Ray decided for his fictional detective character Feluda.” The Luxmi Group makes bespoke furniture under the brand Manor & Mews

The Luxmi Group makes bespoke furniture under the brand Manor & Mews

Image: Courtesy Manor & Mews[br]The same logic, of buying the best properties, applied to Luxmi Tea’s acquisition of three estates in Rwanda—Gisovu, Pfunda and Rugabano—in 2019. Rudra, who was a management consultant at Booz Allen Hamilton’s New York office, had visited Rwanda while he was completing his MBA as a Dean’s List student from Columbia Business School. “My father had told me many years earlier that Rwanda produces the continent’s best teas. And the properties we bought are in some of the best tea-growing regions of the country.”

Conditions such as the volume and intensity of rain, the duration of sunlit hours in a day, temperature, altitude and soil are the most important factors that influence the growth of tea leaves, says Atul Rastogi, head of operations, Luxmi Teas. “Regional variations, both of quality and yield, are large among the different tea growing regions of the world. For example, teas planted near the Equator have higher productivity due to longer sunlit hours. Central African teas on the highlands benefit from temperate weather and rainfall almost throughout the year, resulting in better quality and factory capacity utilisation,” he says, adding that lower or negligible pest activity is another inherent advantage Africa has over Northeast India.

Gisovu teas—among the world’s finest—are grown in the Western Province of Rwanda, also known as ‘The Land of a Thousand Hills’. The bright, brisk and golden teas grow at elevations of up to 8,100 feet, some of the highest grown teas in the world.

Luxmi Tea and The Wood Foundation Africa (TWFA), a UK-based philanthropic investor, bought controlling stakes in Gisovu and Pfunda through their joint investment vehicle, Silverback Tea Company. While for Luxmi this represents their first investment in Africa’s highest quality of black CTC teas, for TWFA it is an opportunity to improve the lives and livelihoods of thousands of smallholder tea farmers by boosting the quality and yield of produce.

In Rugabano, Luxmi Tea and TWFA have undertaken the fresh planting of 4,400 hectares as part of a greenfield project, with grants from UK’s Department of International Development and help from the Rwandan government. “A lot of people were surprised that not only were we buying existing tea estates, but also investing in a greenfield project,” says Rudra. “This estate will begin to produce teas in four to five years from being planted.” Luxmi’s estates in Africa now produce about 5 million kg of tea a year, and is expected to soon reach 15 million kg.

Handmade heritage

Almost as old as Luxmi Group’s tea business is Obeetee, its carpet-making business, which has manufacturing units in Jaipur, Panipat and Mirzapur. Named after its three founding fathers—FH Oakley, FH Bowden and JAL Taylor—the company was set up in 1920, and acquired by Dipankar Chatterjee in 1998. “I acquired the company and sent Rudra there to learn and eventually run the business,” he says. It was pretty much in the same way that Dipankar himself had been sent off by his father to a tea estate in Shyamguri, in Assam, right after he had finished college.

“When I rejoined the Luxmi Group in 2007, it was to run Obeetee,” says Rudra, who is the chairman of Obeetee. “With the global financial crisis looming, I thought I could translate some of the work I had done as a management consultant at Booz Allen Hamilton into helping this company this was a time when customers were becoming more professional. I believed we could become a design leader, and a leader in social accountability.”

Over time it became much more innovative in design, by partnering with Parsons School of Design. Today, with 90 percent of its revenues coming from retailers and enterprise clients in the US, Obeetee has an office in New York. Clients in the hospitality sector include boutique hotels such as New York’s Sheraton Brooklyn, Soho House and Beekman Hotel, and design outlets such as Michael Kors’ retail stores. In recent years, the company has tied up with fashion designers such as Raghavendra Rathore, Abraham & Thakore, and Tarun Tahiliani to produce unique pieces of craftsmanship and design.

Traditional hand-made carpets are made with natural fibres like wool and silk. Resilience is one of the most sought-after properties of any fibre used to make rugs, and is found to be the best in Indian wool. Although silk is available in India, imported silks have gained ground over time due to price advantages.

“Like in the textile industry, carpets are also being driven by alternative man-made materials like viscose, polyester and nylon, in addition to other natural fibres like linen, jute, hemp, sisal, and cotton,” says Angelique Dhama, marketing head, Obeetee. “Sourcing is now distributed across the globe, unlike previously being available at a single marketplace. Organic, sustainable, recycled, eco-friendly or bio-degradable and responsibly-sourced are the new norms for sourcing raw material.”

Customer preferences, too, have seen a dramatic change in the recent past for this century-old business. “Traditional, high-knot carpets—with 200 to 285 knots per square inch—were usually acquired as heirloom pieces,” says Dhama. “However, with the addition of millennial customers, carpets are being looked upon as fashion articles, and there is an increase in demand for rugs with knots as low as 15 per square inch. The number of consumers for high-end, hand-knotted carpets has drastically come down.”

Cheaper machine-made products have also forced the hand-made industry to consider them, thereby making the once-strong artisan base almost jobless. Low-priced products also do not allow for any margins, which makes it difficult for manufacturers to keep the artisans motivated enough to continue the tradition. “We have made carpets for the Oberoi Hotels and the Rashtrapati Bhavan, but we also want customers to be able to go online and buy an Obeetee carpet,” says Rudra. “Obeetee has had a healthy growth rate in the last 20 years and has emerged as the largest company in the industry.”

Modern musings

“Because I visit Obeetee customers and see furniture from around the world, and I also grew up seeing great furniture being made here, especially for the tea estates, I wondered why these customers could not buy furniture made by me,” says Rudra, as he recalls thinking of starting his furniture vertical. He subsequently met British designer David Salmon to build a company out of the UK. “This was because India does not have today the same knowledge of furniture-making that it did in the past.”

Salmon, advisor at Manor & Mews, is known around the world as the designer of furniture for the rich and famous. Trained in antique restoration, he has created pieces for the Royal Palace at The Hague, the Supreme Court of the United States, Arab heads of state, embassies in the UK, and royal households around the world. Salmon opened his first showroom in London in 1989, and subsequently expanded to New York, while working with the world’s best interior designers.

“Mr Chatterjee saw me in my London furniture showroom, where we sell high-end furniture that we make in England,” says Salmon. “He had the aspiration to start an India-based furniture business and given the global position that China and Vietnam have in furniture making, it gives a clear position to begin a furniture business in India.”

Salmon went on to visit Obeetee’s carpet-making units in Mirazpur, and became familiar with its history, and the culture of the business. “I fell in love with it, and also with the reason they wanted to get into the business,” he recalls. “I loved what they wanted to do for the future of the business, and for India and the people.”

The Manor & Mews line of furniture is at a much lower price point than Salmon’s other lines, which he calls “the Rolls-Royce of furniture”. The broad design philosophy of the company is to anticipate trends, particularly in the US. “They have a different aesthetic look compared to Europe,” he says. “It is calmer, and exudes a restrained elegance.”

Manor & Mews has a factory in Jaipur, and creates bespoke and high-end furniture from sustainably sourced wood such as oak, acacia and pine. What it also uses is more than 200 varieties of veneers that are sourced from around the world. Clients include the best global hospitality players, and there are plans to eventually sell in India as well.

Plans of action

As Luxmi Group moves towards making its products directly available to retail customers, there are several factors and challenges.

For enterprise clients, for instance, Obeetee makes carpets only once the design and details have been approved by the client and an order has been placed. For retail clients, however, “the risk of holding inventory, predicting trends, designs and aesthetics will play an important role as carpets are now being looked upon as fashion articles”, says Dhama. “The presence of machine-made, cheaper products, cheaper materials will directly compete with the high-quality, hand-made products retailed through company-owned stores. The lack of product knowledge among end-customers will prove a challenge for this type of business.”

Rudra adds that as the business becomes more customer-oriented, “We are seeing more clients requiring us to do customised products in terms of colours, shapes, and textures. Carpets and furniture are being directly dispatched from the factory in India to global customers. This is an opportunity, but also requires significant strength on India’s logistics infrastructure.”

The company is taking both online and offline routes to reach retail clients. While it now sells Luxmi Tea through its website, Makaibari’s website also has monthly and annual subscription schemes for some of its varietals Obeetee launched its flagship store in Delhi last year, and is planning an online launch of products this Diwali.

First Published: Sep 21, 2020, 10:41

Subscribe Now