Sports: India's reckoning with racism, at long last

Indian sportspersons have long endured racist jibes, and caste, gender or regional bias. As #BlackLivesMatter trends, it's now time for them to speak up

West Indian Darren Sammy (right), seen here with his former IPL teammate Ishant Sharma, has accused some of his Sunrisers Hyderabad teammates of calling him ‘kaalu’

West Indian Darren Sammy (right), seen here with his former IPL teammate Ishant Sharma, has accused some of his Sunrisers Hyderabad teammates of calling him ‘kaalu’

Image: Stephen Pond / Pa Images Via Getty Images[br]In an Instagram video posted on June 9, cricketer Daren Sammy expressed his displeasure at being called ‘kaalu’ (dark-skinned) by some players of his Indian Premier League (IPL) team, Sunrisers Hyderabad, in 2013-14. “I instantly got angry knowing now what it meant. I saw no problem with it then because I was ignorant… I thought it was uplifting and about being a strong stallion. There was laughter whenever someone called us that. It wasn’t funny, it was degrading… you can understand my frustration and anger,” the West Indian cricketer said while revealing that his IPL teammate, Thisara Perera of Sri Lanka, was also addressed with the same name because of his skin colour.

Sammy’s remarks came in the wake of George Floyd’s death in Minneapolis, USA, on May 25 and the anti-racism protests that ensued. Accused of producing a counterfeit bill to buy cigarettes, Floyd died after police excesses, including an officer kneeling on his neck for over 8 minutes, during which the 46-year-old lost consciousness for 80 seconds. #BlackLivesMatter was a social media trend for days and the most-used hashtag on placards as people on the streets called out police brutality and the inhumane treatment meted out to a section of society.

Watching comedian Hasan Minhaj’s show helped Sammy understand the context of what he was being called by his Sunrisers Hyderabad teammates. It wasn’t endearment, as he had thought or was made to believe. The cricketer’s decision to speak up about it gave other sportspersons—Indian and global—the courage to openly condemn racism—casual or intentional—and discrimination based on caste, religion, ethnicity and gender.

In the last couple of months, these conversations have gotten louder and the results are visible both on and off the field. During the ongoing England-West Indies Test series, both teams are sporting a Black Lives Matter logo on their shirts, while the players took the knee before the start of the first match in Southampton on July 8. Mercedes announced a new all-black car for the 2020 Formula One season to support the movement while Lewis Hamilton and 13 other drivers knelt at the start line before the Austrian Grand Prix with ‘End Racism’ written on their T-shirts. The Premier League in England and Germany’s Bundesliga have also allowed players to wear ‘Black Lives Matter’ on their jerseys and take the knee. F1 drivers take the knee on the grid in support of the Black Lives Matter movement ahead of the F1 Grand Prix in Austria on July 5

F1 drivers take the knee on the grid in support of the Black Lives Matter movement ahead of the F1 Grand Prix in Austria on July 5

Image: Peter Fox / Getty Images[br]Meanwhile, Johnson & Johnson stopped selling skin whitening products closer home, fast moving consumer goods major Hindustan Unilever Limited rebranded its popular brand Fair & Lovely as Glow & Lovely, and Shaadi.com decided to remove the ‘fairness’ search filter on its matrimonial site.

The fight to be treated as an equal, though, may have just started. Change is still a far cry, according to Indian sportspeople who have been at the receiving end of abuse and jibes over the years.

“India is full of racial and communal issues,” says former football captain Baichung Bhutia. He concedes his teammates and he have been racially abused on and off the field multiple times, but that did not have an impact on them because footballers are mentally strong. “A lot of them are not even aware that a racial slur is being hurled at them. Most of these players come from humble backgrounds and have struggled their way to the top. The challenges that these guys have gone through since their childhood are more than just the abuse that is directed towards them or their folks. However, that does not mean this should happen. Strict action must be taken against players and spectators who do this,” says the Arjuna Awardee and Padma Shri, who became the first Indian footballer to play over a 100 games for the country. Shuttler Jwala Gutta has faced abuse for her Chinese ancestry even during the Covid-19 pandemic

Shuttler Jwala Gutta has faced abuse for her Chinese ancestry even during the Covid-19 pandemic

Image: Reuters / Marcelo Del Pozo[br]A bronze-winner at the 2011 World Championships, shuttler Jwala Gutta remembers derisive comments being made about her appearance and skin tone, but she wasn’t aware why she was targeted. “Racism exists in general. When I was young, I was name-called, but I never took it seriously… I never understood that it was racism. I want to believe it was not meant to hurt me. I always drew attention because I was tall, and South India, where I grew up, is obsessed with fair skin,” she says. When she was called ‘chinki’ (of Chinese inheritance), she thought it was “factual”, she adds, because she probably looked like that or it was said in jest. “I didn’t pay attention because I was busy playing. I didn’t get the purpose [of these jibes]. We are Indians after all.” It was only in her late-20s that the Arjuna Awardee realised there was more to it than meets the eye.

When people started calling her ‘Nepali’ and giving her similar tags, Gutta figured it was intended to be offensive. During the Covid-19 pandemic too, some Twitter users described her as “China ka maal (Chinese goods)” and “half corona” because her mother is Chinese. “In the last 10 years, because of social media, things have gone haywire. I face it [abuse] a lot more now because I’ve always had an opinion,” says the winner of the gold and silver medals in the women’s doubles at the 2010 and 2014 Commonwealth Games, respectively.

Sportspeople from Northeast India and other remote areas of the country have been vocal about the bias against them and the misconception that they are the “outsiders” in their own country. When Indian football captain Sunil Chhetri was involved in a live Instagram chat with cricket skipper Virat Kohli in May, a user wrote, “Yeh Nepali kaun hai [Who is this Nepali]?” Sikkim-born Bhutia was called Chinese on Twitter after his tweet on the recent India-China standoff. Six-time world amateur boxing champion MC Mary Kom in 2013 broke down at a media event in Mumbai, accusing officials of discriminating against her because of her race. “Okay, I am from the Northeast, no problem… but I am Indian,” said the boxer from Manipur. Baichung Bhutia, the former football captain of India, has admitted there are communal and racial issues in India

Baichung Bhutia, the former football captain of India, has admitted there are communal and racial issues in India

Image: Matthew Ashton / Ama / Corbis Via Getty Images[br] Both the Secunderabad-born Chhetri and Kom condemned the harassment Northeasterners faced after the coronavirus outbreak. In Mysuru in April, two Naga students were denied entry into a grocery store as the staff thought they were foreigners and carriers of the virus. Days before that, a man was arrested in New Delhi for spitting paan (betel leaf and nut) at a woman from the Northeast and calling her “coronavirus”.

Incidents like these perhaps grab headlines during a crisis, but the malaise runs deeper than stray incidents. And it doesn’t spare the famous either. Luge champion Shiva Keshavan was born to a Keralite father and an Italian mother. Born and brought up in Himachal Pradesh, he says there are many undertones to racism that people experience in their daily life. Sometimes it is due to your looks, what your name is or how you talk. “Although I was born in Himachal and was of Kerala descent, I was not accepted as a local. I represented Rajasthan in the nationals in 1994. When I began winning, I suddenly became the son of the soil,” says Keshavan, a six-time Olympian. Luge champion Shiva Keshavan has been called a Taliban and mad cow in Europe

Luge champion Shiva Keshavan has been called a Taliban and mad cow in Europe

Image: Ryan Pierse / Getty Images[br]He adds that racism is a complex issue and one can face it anywhere. The way to deal with it, he says, is to engage with the person and help them realise it’s wrong. “Racism stems from ignorance. You perceive something to be different and don’t know what to do with it,” says Keshavan, adding he was called “Taliban” and a “mad cow” in Europe, but such comments only reinforced his determination to do well.

Sledging is an integral part of sport, but such vitriolic barbs are thrown at opponents not just to demoralise them. They stem from the prejudice, hatred and misunderstanding that people from one community may have for those from another. In his autobiography, English cricketer Moeen Ali admits being really angry on the field after he was called Osama (bin Laden)—the 9/11 terror attacks mastermind—by an Australian player during the first Ashes Test at Cardiff in 2015. Many others have endured similar vicious taunts and racial remarks.

Former India opener Aakash Chopra recalls batting in an English league game and repeatedly being called a ‘Paki’ by two South Africans while he was at the non-striker’s end. “I was definitely perturbed because it went on for too long. They said other things as well. I was only partially aware then… but as brown-skinned people, we do encounter such things from time to time,” he says, adding that calling someone ‘gora’ (white) is also racial abuse. “White people are also subjected to racism and it has happened in our part of the world too. We did call [former Australian cricketer] Andrew Symonds a monkey at the Wankhede Stadium [in 2007]. It happened right under our noses.” Vasudevan Baskaran, captain of the Indian hockey team that won the gold at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, has been called ‘kaaliya’ and ‘idli sambar’ by spectators for his South Indian roots

Vasudevan Baskaran, captain of the Indian hockey team that won the gold at the 1980 Moscow Olympics, has been called ‘kaaliya’ and ‘idli sambar’ by spectators for his South Indian roots

Image: Getty Images[br]Spectators can get under players’ skins with their chatter. Vasudevan Baskaran, captain of the Indian hockey team that won a gold at the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, felt bad and irritated when people passed disparaging remarks about him. “Sledging in India is not about race or religion. It is zonal or state-related. I am from Tamil Nadu and if I go to Bhopal, for instance, they’ll call me ‘Madraswala’. When I would be positioned near the stands, the spectators would shout, ‘Oh kaaliya, ball pass kar [You dark-skinned guy, pass the ball]’ or ‘idli sambar, kya kar raha hai [What are you doing]?’ Since I wasn’t well-versed in Hindi then, I did not know the connotations… later, I started giving it back,” says Baskaran, adding that he was endearingly called ‘kaalia’ by his teammates and did not mind that. “We never took it to heart, but if someone overdid that outside the field, it hurt. It affects everyone if anyone says it doesn’t, it’s a lie.”

In fact, the Arjuna Awardee says he and his mates—former tennis players Vijay Amritraj and Jayakumar Royappa—at Chennai’s Loyola College were called “dark, darker, darkest”. Baskaran believes times have changed, though, and there should be no place for racism. “Sledging on religion and colour should stop because it can affect youngsters too. Sport does not have any religion, caste or colour.”

However, in a multicultural and multilingual country like India, it’s very difficult for these factors to not come into play. Performance alone is not the metric for selection, according to many. Gutta, for instance, says emphatically, “Casteism exists… there’s so much of caste discrimination in sport. Why are only Telugus mostly representing the country in badminton since the last decade? Can’t the others play?” She recalls the time when a prominent person introduced her to an accompanying individual with the words, ‘Yeh hamari beti hai [She is our girl]’. Then only 18, the bemused badminton player asked her father, who was present there, if they were related. He told her that the person was referring to their caste.

Cricketer Snehal Pradhan says, like racism, sexism is another problem dogging Indian sport

Cricketer Snehal Pradhan says, like racism, sexism is another problem dogging Indian sport

Image: Mark Nolan / Getty Images

Former India cricketer Snehal Pradhan tells Forbes India: “Once you are on the field, it is not a factor, but I am sure it’s a factor when it comes to the opportunities in getting to the playing field.” She believes Indian women in sport are not going to be as concerned about racism as having a safe environment. “The thing about wider problems and what’s happening in society is that they come after you solve the basic problems. The ecosystem is built for boys and men to come in. You need to be more proactive when it comes to women. For example, just basic things like changing rooms. My experience was that on many grounds, there weren’t changing rooms for women while the boys changed in the open,” says Pradhan, who last represented the country in 2011.

She also remembers a friendly club match in 2013-14 when the opponents refused to play with a girl. However, she dismisses it as a one-off instance. Sexism, though, remains an issue plaguing sport. Pay disparity, inadequate facilities and discrimination towards women are the most glaring problems. Gutta cites the example of selecting four girls and 10 boys in the national badminton team. “If this is not sexism, what is? Why can’t you send 10 girls and 10 boys? How will they perform if you don’t give them an opportunity? If you look at the last decade, only girls have been performing well. Also, when women speak up there is a problem,” she claims.

India’s diversity and geography mean the battle against racism and discrimination requires a sustained and Herculean effort to bring about change. “Before you reach the international stage, people from certain regions and of certain origins can have a difficult time in getting opportunities. At that level, the system is not fair,” says Keshavan. “The world is not a sterile place. But sport itself is a great means to end racism... you earn respect on the field and it builds character.”

Chopra calls for sensitivity and a change in mindset, and hopes the conversation on the subject leads to greater awareness. “Ignorance is not bliss in this case. That should not be an excuse either. If I have erred, even inadvertently, I should be sorry about it. It is like a people’s revolution… the onus is on individuals,” he says.

Pradhan, who says there is “casual colourism” in the country, believes it will take a generational change to see some results. “When the younger generation—which has grown up in a different world—takes charge, things will change. It’s not going to change overnight. Some of these movements will accelerate things here and there. But for it to be meaningful and deep, it will take time,” she says.

While Bhutia wants the offenders punished, Baskaran emphasises on bringing in strict laws to deter players from crossing the line. He cites the example of the World Anti-Doping Agency that promotes a clean sporting environment and wants elements like the red card to have harsher penalties like a six-month ban or a two-game ouster, depending on the gravity of offence. He also hopes sportspeople highlight such ills regularly. “Those who are affected should speak up. You cannot support something that is not good for Indian sport and world sport,” says Baskaran.

Gutta concurs. “The way to end this is for the good people to not remain silent. There are few who speak. People who have nothing to lose are also not speaking. That is the problem,” she says.

Crossing the Line

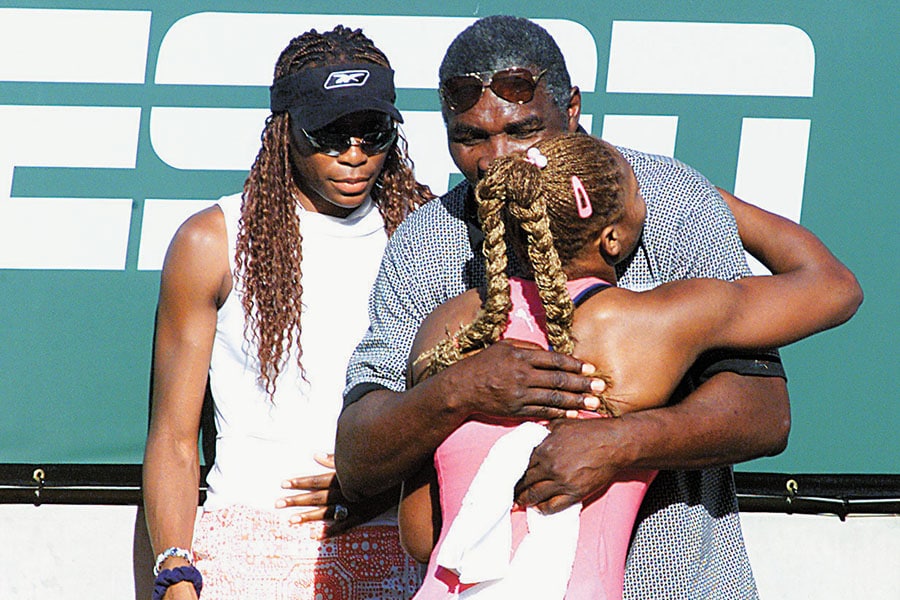

Some global sportspeople who faced racist comments Tennis player Serena Williams (in pink) faced racist slurs from spectators in 2001

Tennis player Serena Williams (in pink) faced racist slurs from spectators in 2001

Image: Mark Nolan / Getty Images

Tennis

Serena Williams: When Serena Williams faced Kim Clijsters in the Indiawells final in 2001, she was greeted with boos and racist epithets at the tennis court. “It was like this echo, it was so loud I could feel it in my chest,” said Serena, then 18. The winner of 23 Grand Slams (singles) won the trophy, but cried all the way home.

Sumit Nagal: In a column for Hindustan Times, India’s top-ranked singles men’s player admitted he’s often been singled out in a group merely because he’s darker. “I have been questioned more every time I get out of the plane in a few countries because of my colour,”

wrote Nagal.

Football

Antonio Rudiger: The Chelsea defender was subjected to monkey chants during the team’s 2-0 win over Tottenham Hotspur in 2019. “It’s just a shame that racism still exists. When will this nonsense stop?” he tweeted after the Premier League game.

Ashley Cole: The English player and his teammate Shaun Wright-Phillips were at the receiving end of racial jibes when England played Spain in 2004. Fans made monkey noises every time they touched the ball. The latter admitted it was demoralising and that he wanted to walk off the field.

Formula One

Lewis Hamilton: Mercedes team principal Toto Wolff has said world champion Lewis Hamilton was racially abused as a child and he still carries those scars. “...he was the only black kid among the white kids... he was abused on the track,” Wolff said.

Athletics

Bianca Williams: Sprinter Bianca Williams accused the London police of racial profiling. Her partner, sprinter Ricardo dos Santos, and she were removed from their car and handcuffed in front of their three-month-old son in July.

Brandon McBride: The Canadian runner said he was once chased in Mississippi by people wielding shotguns and shouting racist slurs.

Cricket

Hashim Amla: Commentator Dean Jones said “the terrorist has got another wicket” on air after South Africa’s Hashim Amla took a catch during a Test match against Sri Lanka in 2006.

Jofra Archer: The England pacer was abused by a fan during the first Test against New Zealand in 2019. “It isn’t ever acceptable. I will never understand how people feel so freely to say these things to another human being,” he wrote on Instagram.

Sarfraz Ahmed: The former Pakistan captain was caught on the stump microphone, abusing South Africa’s Andile Phehlukwayo during a one-day international last year. He addressed him as a “black guy” and asked where his mother was sitting. Ahmed was suspended for four matches and apologised to Phehlukwayo later.

First Published: Jul 18, 2020, 06:38

Subscribe Now