It didn’t take long for Dhariya—whose mother worked in the social sector and for women’s empowerment—to figure out the answer: To landfills and water bodies, unsegregated and unhygienic, while their super-absorbent polymer sucked up vast reserves of the freshwater supply. “That immediately told me there was a problem to address," he adds.

According to the 2011 Census, around 336 million Indian girls and women are of the reproductive age, meaning most of them would be menstruating. Of them, around 121 million, mostly urban women, are expected to use disposable sanitary pads, says data by Menstrual Health Alliance India, a national-level inter-agency advocacy group.

Couple this with the fact that each sanitary napkin, with its constituent 90 percent plastic, takes somewhere between 500 and 800 years to decompose. Which means the first known disposable pad, the Southball Pad manufactured in 1888 in the Western world, is still contributing to waste somewhere on the planet. “This was a trigger point for PadCare Labs," says the 25-year-old.

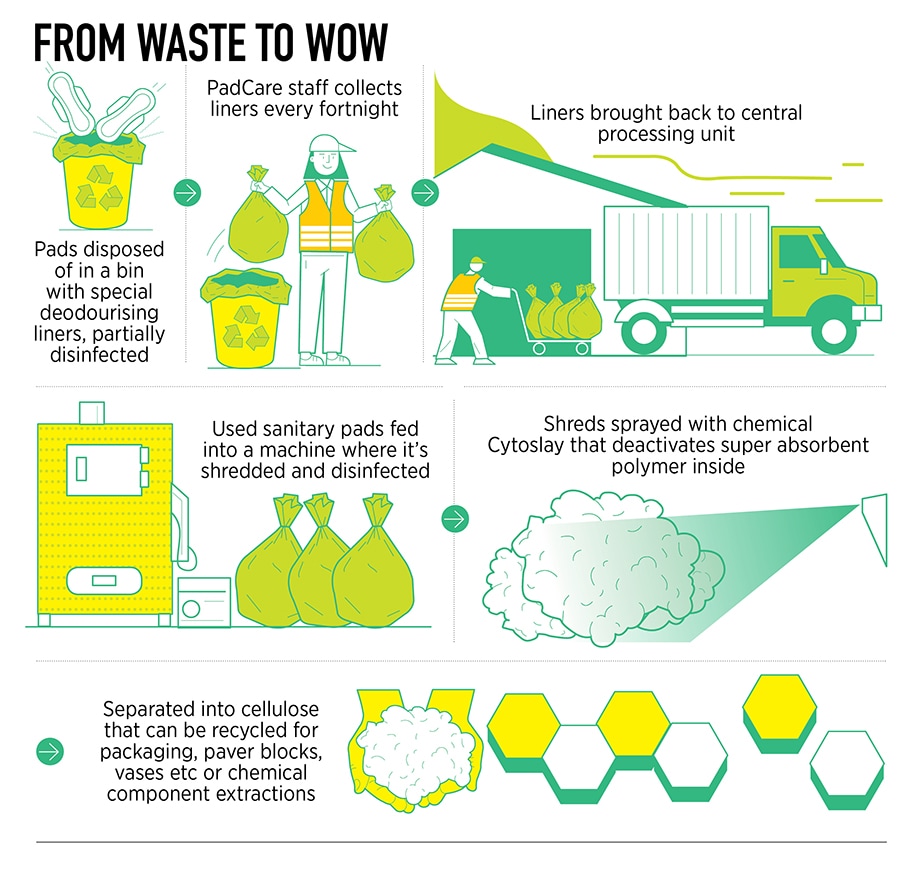

In 2018, a year after graduating from college, Dhariya set up the company and designed a machine that could disinfect and shred used sanitary napkins, pass it through a solution to deactivate the super absorbent polymer and separate the components into recyclable cellulose that could be used in the packaging industry, or to manufacture vases, paver blocks, what have you. In 20 minutes, this machine can break down 50 pads.

![]() The technology is split into two ends: The front an automated bin installed at washrooms where used sanitary napkins are disposed of while, at the back, a 10-foot central processing unit (“a washing machine with a shredder on top"—that’s how Dhariya describes it) that converts those unhygienic, used pads into separated cellulose for upcycling. Which means no longer will the ragpickers have to trawl through filthy sanitary waste, nor would they add up to the global toxic heap.

The technology is split into two ends: The front an automated bin installed at washrooms where used sanitary napkins are disposed of while, at the back, a 10-foot central processing unit (“a washing machine with a shredder on top"—that’s how Dhariya describes it) that converts those unhygienic, used pads into separated cellulose for upcycling. Which means no longer will the ragpickers have to trawl through filthy sanitary waste, nor would they add up to the global toxic heap.

Dhariya started going commercial in March 2020 and, despite a dip during the furious second Covid wave in April and May 2021, has onboarded 16 corporate clients in Mumbai and Pune, including the likes of P&G, JSW and Raymond. Almost 550 units of the bins, which are fitted with special liners developed in-house, which can deodorise and partially disinfect the pads for 30 days, have been installed in the offices of his clients. As of now, he houses a central processing unit at his workplace in Pune’s Pashan, along the Mumbai-Pune highway, but is manufacturing four more for locations across Mumbai, Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Gurugram.

Dhariya’s technology has drawn applause from industry stalwarts like Mahindra Group Chairman Anand Mahindra who tweeted “their work is as important as designing satellites", while his brisk pace of growth—that has spurred him to look for a bigger office space than his current duplex rowhouse in Pune’s Periwinkle Society—has pleasantly surprised his mentors. One among them is Sijo Varghese, manager-innovation and startup, Maharashtra State Innovation Society (MSIS), the government’s nodal agency for executing its startup policy.

![]()

Each year, MSIS selects 24 innovative startups and nurtures them with technical and funding knowhow. PadCares was one of the winners in the 2018 cohort. “We were in a dilemma when we selected PadCares, doubtful whether this product will actually get on the market and can have a business model," says Varghese. “Ajinkya played a clear role in taking that forward. The key differentiation that Ajinkya brings in as a founder is connecting the right ecosystem partners. That helped him scale the prototype into a finished product. He has the ability to identify the right networking agent within the ecosystem at the right time."

The vote of confidence from his backers as well his clients has given Dhariya enough gumption to eye rapid scaleup. Through his three-year journey, Dhariya had received ₹2.5 crore as grants from government as well as private institutions like the Infosys Foundation. In December 2020, he raised his first equity investment—a pre-seed round of ₹75 lakh from the Leap Fund by Birac (Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council, a not-for-profit public sector enterprise set up by the department of biotechnology). Dhariya is now actively looking for investors for subsequent rounds of funding. “The pre-seed round was to take this from the lab pilot to the commercial mode. Now, we are looking for seed funding to scale across Bengaluru, Gurugram and Hyderabad," he says.

![]()

“Our annual recurring revenue just touched ₹54 lakh in September, at ₹4.5 lakh a month. But we are expecting some more corporate orders in the coming months and I think we can reach about ₹1.5 crore revenue at the end of this fiscal," adds Dhariya. “Our growth isn’t in pull mode, instead, the customer is pushing us to expand. We don’t need to work hard to acquire new customers, enough inquiries are coming in already."

*****

Dhariya comes from a business family in Raigad, and that he would eventually move into entrepreneurship once finishing his degree was clear to him despite his inherent dislike for suits and ties (“The blazer hanging in my car is only for official meetings," he laughs gingerly during the photo shoot. “I’m most comfortable in my T-shirts"). He dabbled in a number of sectors during his college—energy, sustainability—but once he ran into the problems of menstrual hygiene management, he was hooked. For a year after graduating in 2017, he worked as an R&D engineer on an Isro project by day, but outside of his office, he devoted his hours to developing the mechanism that would disinfect sanitary pads and plough them back into a closed loop of production and consumption, titled ‘circular economy’ in modern parlance.

His idea won him the Innovation Challenge Award-SoCH (Solutions For Community Health) organised by Birac in 2018. Dhariya was given ₹65 lakh to design, develop and test his solution and come up with a basic prototype. In July 2018, he incorporated PadCare Labs, and started operating from a tiny space at the National Chemical Laboratory (NCL) in Pune, where he was mentored at the Venture Center, among India’s largest science business incubators and a not-for-profit hosted by the NCL.

The early days were difficult. “This was a new space and we had no data. We had to finetune our machine by conducting more than a thousand trials, some at the washrooms at the Venture Center itself," says Dhariya. The initial idea was to mount the machines on the wall, like hand-dryers, and have an integrated processing unit in the washroom itself. “But most cubicles in an Indian washroom don’t have a plug point, or additional water connection for the machine to function. Besides, most women aren’t so much interested in how the pads are processed they just want some privacy and a hygienic disposal," adds Dhariya. “That’s how we came up with the idea of splitting the bin from the processing unit."

![]() Team PadCare Labs: (From left) Amit Jadhwar, operations lead Asif Dharwadkar, general manager, sales and operations Ajinkya Dhariya, founder and CEO Aasawari Kane, research scientist Shriniwas Adhe, product manager

Team PadCare Labs: (From left) Amit Jadhwar, operations lead Asif Dharwadkar, general manager, sales and operations Ajinkya Dhariya, founder and CEO Aasawari Kane, research scientist Shriniwas Adhe, product manager

Image: Mexy Xavier

Says Smita Kale, manager-bioincubation of Venture Center, and a nominee director at PadCare: “His technology, business model and approach have all evolved. Not only has he gone from a shy engineer to a confident business-owner, he’s always interacted with his users and adapted his product to their needs. Understanding your users makes all the

Diving deep into the user psyche has enabled Dhariya to not just alter the design of the machine, but also the disinfection technology—from an expensive ultraviolet-based mechanism to the current chemo-mechanical (with a solution christened Cytoslay), and his revenue model—from paid bins to paid service. Dhariya now provides the sensor-led disposal bins for free and recovers the costs through fortnightly charges of ₹550 per service, for emptying the bins and bringing back the used pads to the central processing unit.

“We realised that most of our clients don’t want to bear a capex but are okay with operational expenses," he says. “We sell the cellulose, the final output, to suppliers at ₹30-40 per kg. It covers our processing cost of the sanitary napkins (at 30 paise per pad), so our net operational cost is zero." Says Varghese of MSIS: “In 2018, the prototype he made wasn’t market-fit. Now it’s ergonomically designed and has taken into account all the requirements of a typical washroom cubicle. It has also taken a leap in terms of the design, right from installing sensors in opening the lid to capturing the details of specific bins through a QR code, the logistics, and also dispersing the output."

![]()

Ajinkya Dhariya with products like plant pots, composite table and paver blocks that are made using the recycled sanitary pads

Image: Mexy Xavier

Along with the bins, PadCare has also developed sanitary napkin vending machines that operate on digital pay. For this, the company has tied up with a number of eco-friendly pad manufacturers. “When a woman disposes a sanitary napkin, chances are she will need another," says Dhariya. “This closes the circular economy loop at a local level."

*****

As he sets off on the growth runway at a frenetic speed, Dhariya now has to contend with the vagaries of expansion—transforming from a scientist to a CEO. He saw an early glimpse of the responsibilities during the first Covid lockdown when his manufacturing facility was shut and he pivoted briefly, using his disinfection technology to sanitise N95 masks when they were scarce in the market, as well as selling a thousand units of a non-alcoholic sanitiser for surface cleaning. He has now transferred the technology to the Kinetic Group. “Before that, I was a products guy, sitting in a room and developing technology," says Dhariya. “But through these months and through the discussion with the Kinetic Group, I began to understand how business works, how to sell."

“I have literally seen Ajinkya and the team grow," says Venugopal Gupta, director, accelerator and investments, Toilet Board Coalition (TBC), a patchwork of members from the private sector, donors and the investment community that helps scale market-based solutions to universal access to sanitation. “When they entered our accelerator programme in 2020, they had a product lens. They were highly technical people in the menstrual hygiene management sector. But I’ve seen them evolve into a business mindset. They’ve signed up customers fast, they are getting their communication in order. They’ve created a momentum."

![]()

For pan-India expansion, Dhariya is exploring the franchise route at the B2B2C level: Sell the machines to operating partners who will take care of on-ground operations, like installing bins, servicing and back-end processing. “That will help us cater to corporates who have multiple offices across cities, but prefer to stick to the one-vendor policy, while maintaining unit economics," he adds.

Besides, he’s aware he can’t foray into households with the bins. For that, he’s launched a paid pilot project of a sanitary disposal pouch. Why will women pay for pouches that are already provided for free by manufacturers like P&G? “Because of our packaging. Most women consider the current ones provided by the manufacturers as part of the pads. Only a different packaging gives them a sense of privacy and empowerment," says Dhariya.

![]() Testing bacterial load of the waste to ensure it is within prescribed limits

Testing bacterial load of the waste to ensure it is within prescribed limits

Image: Mexy Xavier

Will this bring PadCare in collision with deep-pocketed multinationals, who operate in the same space? Sure, there will be enough giants to buy out the company, but Varghese of MSIS believes Dhariya’s strategy of connecting various ecosystems in the menstrual hygiene management space will help them stand by themselves.

Agrees Gupta. As part of TBC’s accelerator programme, PadCare was mentored by US-based personal care giants Kimberly-Clark. “That wouldn’t have been possible if they looked at PadCare as a competitor," says Gupta. Besides, PadCare has also tied up with P&G that manufactures sanitary napkins exclusively for the vending machines run by the company. “PadCare isn’t in collision with the companies, rather it complements them," adds

Besides, even though PadCare operates in a niche space, with a target group of menstruating women, the space is big and stable enough, with younger members joining the group as the older ones exit. Given the pace at which urban centres are transitioning, moving to something like a bio-friendly menstrual cup is going to take long. When that does happen, “I’m sure PadCare will be ready with a new, tweaked product. They’re already testing their technology on diapers," says Varghese.

![]() PadCare’s sanitary napkin vending machines that operate on digital pay

PadCare’s sanitary napkin vending machines that operate on digital pay

Image: Mexy Xavier

And while bio-degradable sanitary napkins have started to arrive in the fast-growing fem-hygiene market, they still need to be decomposed. “Maybe eight months instead of 800 years," says Dhariya. “But decomposing also means we are just ending its life. With our machine, you can extract value out of it."

By trying to emerge as a one-stop solution for menstrual hygiene management, PadCare is gathering the stomach and steam to outrun its competitors in the sector, which is slowly starting to get crowded. Will it succeed? The experts are upbeat. Says Varghese: “Six years down the line, I feel PadCare will be a unicorn in the space."

Ajinkya Dhariya, founder and CEO PadCare Labs

Ajinkya Dhariya, founder and CEO PadCare Labs The technology is split into two ends: The front an automated bin installed at washrooms where used sanitary napkins are disposed of while, at the back, a 10-foot central processing unit (“a washing machine with a shredder on top"—that’s how Dhariya describes it) that converts those unhygienic, used pads into separated cellulose for upcycling. Which means no longer will the ragpickers have to trawl through filthy sanitary waste, nor would they add up to the global toxic heap.

The technology is split into two ends: The front an automated bin installed at washrooms where used sanitary napkins are disposed of while, at the back, a 10-foot central processing unit (“a washing machine with a shredder on top"—that’s how Dhariya describes it) that converts those unhygienic, used pads into separated cellulose for upcycling. Which means no longer will the ragpickers have to trawl through filthy sanitary waste, nor would they add up to the global toxic heap.

Team PadCare Labs: (From left) Amit Jadhwar, operations lead Asif Dharwadkar, general manager, sales and operations Ajinkya Dhariya, founder and CEO Aasawari Kane, research scientist Shriniwas Adhe, product manager

Team PadCare Labs: (From left) Amit Jadhwar, operations lead Asif Dharwadkar, general manager, sales and operations Ajinkya Dhariya, founder and CEO Aasawari Kane, research scientist Shriniwas Adhe, product manager

Testing bacterial load of the waste to ensure it is within prescribed limits

Testing bacterial load of the waste to ensure it is within prescribed limits PadCare’s sanitary napkin vending machines that operate on digital pay

PadCare’s sanitary napkin vending machines that operate on digital pay