Anant Goenka: One for the road

Innovation and customer focus have ensured that Anant Goenka's Ceat is motoring ahead in the Indian market

Being Harsh Goenka’s son puts a certain amount of pressure, says Anant. And so, he adds, he has to establish his capability

Image: Mexy Xavier

Forbes India Leadership Awards 2017: GenNext Entrepreneur

I’m not socially- or media-inclined,” says Anant Goenka, managing director (MD) of Ceat Ltd. Instead of ordering his staff, he switches on the AC in his cabin and picks up bottles of mineral water to offer us. The personal touch is evident. As is his mild, soft-spoken manner in the course of his interview with Forbes India.

But his mellow exterior belies an understated aggression. Since taking over the reins at Ceat in 2012, Anant has transformed the tyremaker, part of the storied RPG group set up by his grandfather Rama Prasad Goenka in 1979, into one of the fastest growing companies on the Bombay Stock Exchange. Its market cap has risen almost 20-fold from ₹350 crore in 2012 to ₹6,700 crore (as on October 2017). Net sales have surged from ₹4,649 crore in FY12 to ₹6,376 crore in FY17, and net profits zoomed from ₹18 crore to ₹362 crore during the same period the latter growing at a compound annual growth rate of 82 percent.Sitting at the company’s headquarters at the RPG House in Mumbai’s Worli area, where contemporary artworks dominate the walls—father Harsh is an avid collector—Anant, 36, outlines his strategy: Shifting focus to higher-margin segments, rapid innovation, aggressive marketing and management experimentation, all the while keeping the customer at the centre.

He credits his predecessor Paras Chowdhary, who helmed Ceat for 11 years from 2001, for setting the stage for him. “By 2012, when I came in, the aspect of survival was over,” says Anant, referring to the early 2000s when Ceat went through a patchy period financially.

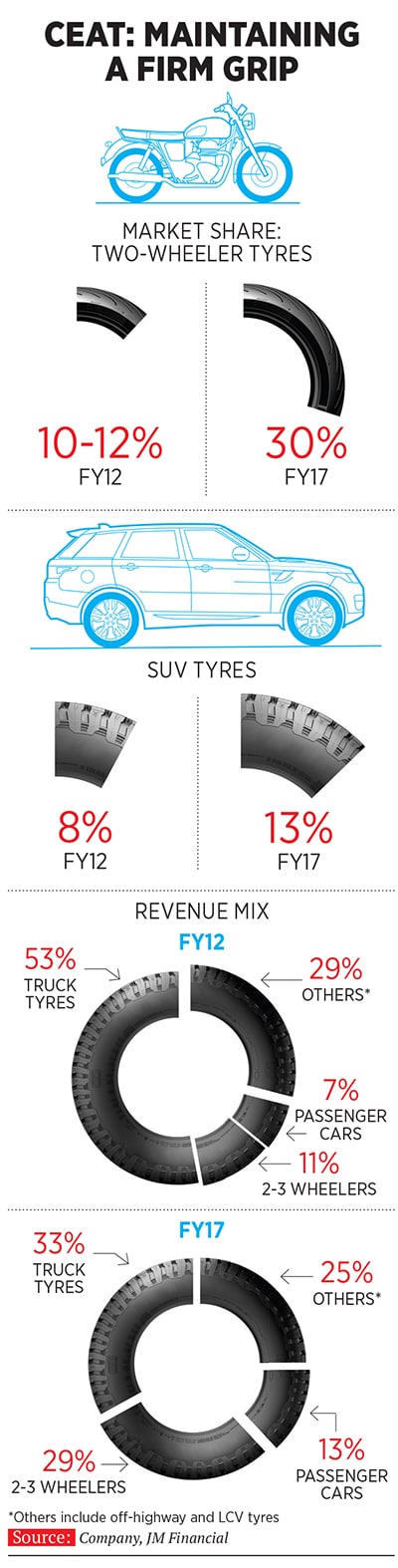

At the time, a majority of the company’s sales came from cross-ply tyres—a dated method in which tyres are manufactured by criss-crossing a series of plies—used in commercial vehicles. But it’s a fiercely competitive segment with painfully low margins. Anant was quick to realise this and, in a “key contribution”, as Harsh puts it, changed the company’s product mix by strengthening its play in the higher-margin two-wheeler and SUV market. Today, the passenger vehicle segment, which includes two-, three- and four-wheelers, accounts for 42 percent of Ceat’s sales, while commercial vehicles, including trucks and buses, account for 33 percent.

And Harsh, who serves as chairman of the RPG group, is a happy man. “I did wonder whether Anant will perform well or not,” he confesses, adding that his own promotion to the top spot at Ceat at 24 was an incorrect decision. “I was still a novice and learnt the ropes as I went along. I didn’t want the same [for Anant] and the company to suffer. But he has proven all my apprehensions wrong,” beams the 60-year-old.

*********

In the mid-2000s, under Chowdhary’s leadership, Ceat had identified a gap in the European market for off-highway tyres used in tractors and other off-the-road vehicles. At the time, the company was running a low-margin business in this category, catering largely to government tenders in the domestic market. “It was only a pricing game so it was no fun,” recalls Anant, who had by then completed his undergraduate degree at the Wharton School of Business as well as a one-year stint at Hindustan Unilever, working across functions and locations in India. But the European market was lucrative: It offered 20 percent margins compared to the 5 percent available in India. So a new business unit was created and Anant, who had been earning his spurs within Ceat from 2004, first as sales manager for Navi Mumbai and then as sales head for Maharashtra, was asked to run it. Swiftly, he moved from selling 80 percent of these specialty tyres domestically, to 80 percent in Europe.

Soon after, Anant went off to pursue an MBA at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University in Illinois. On his return in 2007, he worked with KEC International, the power transmission infrastructure arm of the RPG group, for three years, focusing on the supply chain. During this time, Chowdhary went on to make important capacity building investments at Ceat: He commissioned an R&D facility as well as a ₹700-crore radial tyre facility—a newer manufacturing process compared to the cross-ply method that lends tyres more longevity—for passenger cars and trucks, both in Halol, Gujarat.

In 2010, Anant was appointed deputy managing director at Ceat and, in two years, when Chowdhary decided to call it a day, he was promoted to the top. “He is very mature and intelligent,” the outgoing MD told Forbes India at the time of his departure. The then 30-year-old Anant, he said, had been well groomed and was ready to take over.

A key aspect of this “grooming” was Anant’s weeklong stint in Tokyo for a programme that involved classroom training on the Japanese management strategy of total quality management (TQM). Visits to the factories of Toyota, Denso and Hino Motors—Japanese manufacturing champions who pioneered TQM in the ’50s and ’60s—were part of the mix. It was there that Anant understood that “quality” wasn’t something left to the quality controller at the end of a production line, but was, in fact, representative of a culture.

*********

By 2012, Ceat was in a comfortable position with all the “positive changes” that Chowdhary had brought in. “But the mindsets of people were still towards incremental growth. We were just making sure that we don’t make losses or were able to grow by 10 percent every year,” recalls Anant. “But that wasn’t ambitious enough.” So he regrouped his team and drew up a five-year goal. How could Ceat create value for its customers and draw in higher profits? How could it differentiate itself from competition?

So he regrouped his team and drew up a five-year goal. How could Ceat create value for its customers and draw in higher profits? How could it differentiate itself from competition?

It was clear to Anant that focusing on the two-wheeler and SUV segments was the key to achieving these goals. Not just because the margins were higher—around 18-20 percent compared to the just about double digit margins that cross-ply truck tyres bring in, according to industry insiders—but also because competition was limited: MRF, Falcon (Dunlop) and TVS were the only other players in the market. And importantly, customers cared about the tyre they used. “If you offer better value, a good brand or a clear benefit, people will choose your product over others. Whereas truck tyres are more commoditised and pricing-led,” says Anant.

Market surveys carried out by Ceat revealed that on-road grip was of great importance to two-wheeler customers. So the company came up with a tyre design that looked like a rope placed on the tread, something that subconsciously reminded buyers of grip. “Rooted in the study of product semantics, that was quite an innovative thing we did,” says Anant. Simultaneously, Ceat upped its publicity blitz (in absolute terms, advertising and marketing expenses have more than doubled over the last five years and currently estimated at 2-2.5 percent of sales). Campaigns like “Idiot Safe”, which showed how Ceat’s tyres with their sturdier grip promised the protection motorists needed from reckless pedestrians, created a buzz. Similarly, actor Irrfan Khan was roped in to market their SUV tyres.

Even so, distribution posed a challenge. Although Ceat had a good network, it wasn’t good enough for the passenger vehicle segment. It was more geared towards the sale of truck tyres, which was priced at ₹15,000 per tyre and bought in clusters of 4-10, made for a sizeable bill, one that allowed for rural customers to be served cost-effectively. However, in the two-wheeler space, a tyre typically cost ₹1,500 and a mechanic would often buy just two a month.

Ceat decided to overcome this by replicating the model used by fast-moving consumer goods players who sell items of far lesser value, deep into rural markets. It was a first-of-its-kind move in the tyre industry where instead of selling to dealers, Ceat added another layer, the distributor, who, in turn, tapped into their vast network of sub-dealers. The move helped Ceat penetrate all of India’s 600 districts, up from around 200 earlier, helping it notch up a market share of 30 percent in the two-wheeler segment (up from 11 percent in 2012), behind market leader MRF (35 percent). “To capture this kind of market share in such a short period is no mean feat,” says Shyam Sundar Sriram, auto and auto ancillaries analyst, Institutional Equity Research, JM Financial. “What would have been just another tyremaker is today a clear differentiator thanks to Ceat’s product mix, continuously deepening distribution network and brand building efforts.”

By differentiating in this manner, Anant hopes to have insulated Ceat from fluctuations in rubber prices —a key raw material that accounts for 65-70 percent of the industry’s costs. “Input prices movements affect your performance in a quarter here or there. But, in the end, it’s a long-term game. It’s about increasing your competitiveness,” he says.

Strengthening partnerships with original equipment manufacturers (OEM) has also been a key part of Ceat’s strategy. Previously, vehicle manufacturers accounted for a mere 5 percent of the company’s sales however, surveys repeatedly showed that when customers replace tyres, 25 percent usually went with the OEMs. Today, Ceat draws 25-30 percent of its business from such partnerships, including those with Royal Enfield, Bajaj and Hero Honda among two-wheelers, and Mahindra & Mahindra, Tata Motors and Renault Nissan on the passenger car side.

Over the next five years, Ceat has committed ₹2,800 crore to capital expenditure. Already, a greenfield two-wheeler facility is being set up in Nagpur, slated for completion later this year.

With continuous investments, Anant hopes to continue capturing market share in the two-wheeler and SUV segments, while strengthening Ceat’s position internationally. In Sri Lanka, where Ceat has a joint venture with local manufacturer Kelani Tyres, the company dominates with a 50 percent market share. It hopes to replicate this success in Bangladesh too where it is setting up another greenfield unit.

*********

Anant says it’s the out-of-the-box thinking—a key pillar of TQM where every employee is charged with bringing in continuous improvements, both big and small—that has helped Ceat leapfrog, rather than grow incrementally. Consider how Ceat has piloted puncture-proof tyres made of sealant glue that automatically binds together when a tyre is pierced, or how employees on the factory floor bring in efficiencies by taking ownership of the machines demarcated in their area of work. “TQM has completely restructured how we work,” says Anant.

undefinedSince taking over the reins in 2012, Anant has transformed Ceat into one of the fastest growing companies on the BSE[/bq]

He explains the three-tiered thinking process enabled by TQM: First, every organisational goal is linked to Ceat’s long-term, customer-centric vision of enabling safer mobility on the roads. Second, he ensures that the right systems and processes are in place to achieve these goals and, finally, all employees must be fully involved in improvement activities. Such is Anant’s commitment to the principles of TQM that Ceat was recently awarded the Deming Prize, a prestigious quality award from Japan.

“Under Anant, there is excitement within the company about a common goal, which is rewarding for our shareholders,” says Harsh, who gets involved when strategic direction is needed, but stays away from day-to-day operations.

Even so, does the responsibility of being a Goenka feel like a burden for Anant? He pauses and says: “One is initially viewed with the lens of having advanced due to nepotism. Certainly, I’ve grown to where I am because I’m my father’s son and that puts a certain amount of pressure. So you have to establish your capability. That’s the responsibility I have.”

That’s also the thing about achieving success and yet remaining grounded: It’s a winning combination.

First Published: Nov 23, 2017, 06:30

Subscribe Now