The artist and his studio: A museum that will take Jamini Roy's legacy forward

DAG's acquisition of the artist's Kolkata home is not just about preserving his legacy, but setting an example for future, similar initiatives

Tucked away in a quiet, bylane of Kolkata’s Ballygunge neighbourhood stands a house that, for many from the city, might feel like home. Its pale pink walls are offset by green, wooden window shutters, a central stairwell overlooks the road through glass panes, and trees flank the structure on all sides. Representative of homes that were built in the city in the 1940s and 1950s, the house would perhaps be quite unremarkable, had it not been for the fact that it had been the home and studio of one of India’s most prolific and popular modernist painters, Jamini Roy.

Born to a landowning family in 1887 in Beliatore in Bengal’s Bankura district, Roy studied European academic-realist painting at the Government School of Arts and Crafts in Calcutta, where Abanindranath Tagore was vice principal. He began his career painting landscapes and portraits, but soon started experimenting with a more indigenous visual vocabulary. Level surfaces, flattening of design in-depth, and the use of dissonant primary colours were aspects of folk painting that Roy incorporated in his work. Also, he took up the volumetric forms of the Kalighat patachitras.

Roy is known for his distinctive style, inspired by the art and craft traditions of folk artists and sculptors, in particular the simplicity and aesthetics of Santhal life. He was awarded the Viceroy’s gold medal in 1935, the Padma Bhushan in 1955, and elected a Fellow of the Lalit Kala Akademi in 1956. Declared a National Treasure artist in 1976, his works cannot be exported.

In 1949, he moved from his home in North Calcutta’s Baghbazar to the neighbourhood of Ballygunge Place, and built a bungalow, over multiple phases. He lived in this home with his family, till his passing away in 1972.

This March, this home was acquired by DAG with the aim of creating India’s first, world-class, private, single-artist museum and cultural resource centre on the life, work and times of the pioneering artist. The Jamini Roy House Museum is due to open next year.

While carefully restored interiors will bring the artist’s workspaces and his homespun ethos to life, the museum—with a built-up area of 7,284.17 sq ft across three floors, a courtyard with an outhouse of 902.66 sq ft and terrace spaces of 1,616 sq ft—will be equipped with state-of-the-art galleries to house the permanent collection, as well as rotating exhibitions, community spaces like a resource centre and a library, art workshops and event spaces, as well as a museum shop and café to complete the visitor experience. Plans are also being drawn up for academic and cultural programmes.

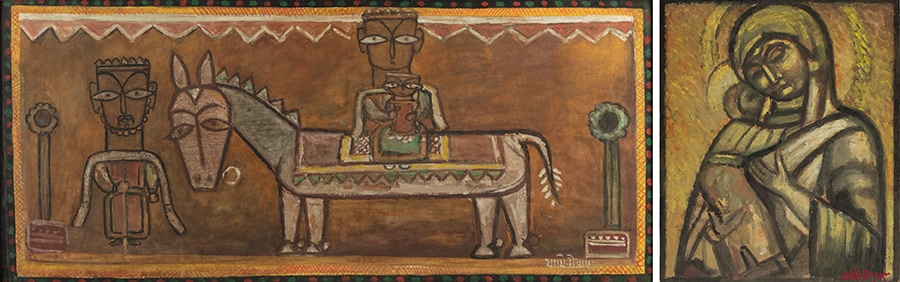

One of India"s first modernists, Jamini Roy developed a unique aesthetic that balanced traditional Indian iconography and materials. From left: Untitled (Flight into Egypt). Untitled (Madonna and Child)

One of India"s first modernists, Jamini Roy developed a unique aesthetic that balanced traditional Indian iconography and materials. From left: Untitled (Flight into Egypt). Untitled (Madonna and Child)

“After the death of Jamini Roy, his son Amiya had petitioned the then-central government that Roy"s studio be acquired by them and converted to a permanent gallery. After a lot of hard work, he succeeded in doing so. The studio was acquired by the government, which bought perhaps more than 100 of his paintings. But ultimately the gallery didn"t happen. Since then, the family wanted something along the lines of a gallery or museum in that house, but we didn"t know how that would actually happen," says Arkamitra Roy, Jamini Roy’s great-granddaughter.

But as the family members aged, they found it increasingly difficult to maintain the structure. “After the family decided to put up the house for sale with a heavy heart, because it was too large and too old to be effectively maintained by a group of largely senior citizens, the news of the sale spread through the grapevine, and DAG heard about it and sent someone to Kolkata in 2018, to make inquiries about the possibility of selling to them so that they may convert it into a museum for Jamini Roy. Our prayers were answered," adds Arkamitra.

The three-storeyed structure, with a courtyard and balconies and terraces at multiple levels, housed Roy’s studio on the ground floor, which he had designed for this sole purpose. This was where he worked, prolifically, met guests and clients, and kept his works. Depending on the time of the year, or the day, he would move into the courtyard—in the shade of a towering mango tree—with his canvases and paints.

Unlike the ground floor, the first and second floors of the house have rooms, kitchens, bathrooms and balconies that were meant for the family to live in. On a wall is written, as though in a large textbook, the English alphabet in bright magenta, while crayon drawings and squiggles spread across other walls. Clearly, a child’s delight. Rooms and corridors open into each other through multiple doors, while skylights provide added light and ventilation. All design elements were meticulously thought out by Roy, with, for instance, signature motifs being repeated across the window and skylight grilles across the house. In more recent years, the ground floor had been rented out to a bank and modified for its use, and was subsequently vacated once again, while the family gradually moved into other residences around the city.

“We approached the family," says Ashish Anand, CEO and MD, DAG. “Part of the house had been given on rent and the family occupied the rest of the spacious building. But they were finding it difficult to maintain. They had offers from various people with different proposals, but were delighted to learn that we wanted to create a Jamini Roy House Museum, and came together and agreed to let us have the building. It is a prestigious project for us, and a humbling one, that we will become custodians to Jamini Roy’s legacy in a manner of speaking."

DAG has had an interest in museums and has mounted museum exhibitions on grand scales, such as ‘Drishyakala’, at Red Fort, Delhi, in 2019 along with the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), or ‘Ghare Baire: The World, the Home and Beyond’, a museum-exhibition of 18th to 20th-century art in Bengal, in the Old Currency Building of Kolkata, with ASI and National Gallery of Modern Art. “Instinctively, we knew that this historical home needed to be turned into a museum and began to make inquiries that have resulted in an acquisition that will pave the way for one of our most exciting projects," adds Anand.

Ashish Anand, CEO and MD, DAG

Ashish Anand, CEO and MD, DAG

The museum is now a work in progress. Anand says that some conservation architects have made proposals, while some others are yet to do so. Once the conservation architects have been decided upon, DAG will involve museum designers. Permissions etcetera are expected to take time, and in the meanwhile DAG will finalise its wish list: Galleries for the permanent collection, galleries for curated shows that will change on a regular basis, auditoriums, a café, a music shop, a library. “We want to make this a lively cultural centre for the city. We hope to open the museum next year and are working towards that goal," he says.***Unlike in the West, in India, it is rare for the homes and work spaces of artists to be preserved for posterity. Given that many artists work within their homes, it is often the families who find themselves as the custodians of these spaces and belongings and struggle to be so. There have been cases, such as that of Jehangir Sabavala (1922-2011), where about 140 of his personal archive items and belongings were donated to the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (CSMVS) in Mumbai.

The preservation and archiving of personal belongings, archives and work tools do not have a fixed template although the end goal might be similar, the route might be different. The donation of Sabavala’s archives to CSMVS is very different from, say, the belongings of Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore that are archived at Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, the university which he founded in 1921, and where he lived for many years, and at his ancestral home in Jorasanko, Kolkata.

Rabindra Bhavana, the museum at the university, was established in 1942, a year after Tagore’s death, with the intention of preserving several hundred of his manuscripts in Bengali and English, hundreds of correspondence, books, paint brushes and sketches for posterity and also for the purpose of research. Rabindra Bhavana also houses Tagore’s personal library and various objects used by him, his voice recordings and thousands of photographs taken of him at different times and places, along with the many gifts, honours and addresses which he received from different parts of the world.

Left: The artist Rembrandt’s house, now a museum in the centre of Amsterdam. Image: Kirsten van Santen/The Rembrandt House Museum.

Left: The artist Rembrandt’s house, now a museum in the centre of Amsterdam. Image: Kirsten van Santen/The Rembrandt House Museum.

Right: A view of Jamini Roy’s ground floor Studio. Image: Courtesy DAG

“This kind of an initiative is very important. In the West, we can plan our visits to, say, the Rembrandt house to get a peek into the artist’s life and work. Spaces like these spark the imaginations of people who admire an artist, by showing them how they lived, and what were their studios like," says Roobina Karode, director and chief curator of the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art. “In that sense, Jamini Roy’s house being taken over by DAG is a good initiative, and it can be a good example for other such initiatives in future. Otherwise, properties such as this would just wither away or be taken over by a builder for some other purpose."

Karode adds that it is not just the homes of artists, but historically important figures, such as William Shakespeare or Anne Franke, which have been preserved in the West. “These are historical figures, and the retention of their homes and their promotion are culturally very important. There are instances where artists’ homes have been kept intact, and nothing has been changed there are also ways to put these properties on the map and make them tourist attractions. So, there are different ways in which this preservation can be done."

“Any single-artist museum focuses on the artist and brings him or her into significance. Not that Jamini Roy needs anything more—he is hugely popular as well as a National Treasure," says Anand. “We have to ensure that the museum experience is so enriching that it brings back visitors again and again. Of course, part of the museum will have galleries with changing exhibitions, including, we hope, international collaborations with cultural institutions and museums overseas to offer ongoing engagements that will make it a lively centre for the arts."***Elaborating on the challenges of converting a family home into a museum, Arkamitra says, “Selling a house is not the same as selling a heritage house. The first thing we needed to obtain was permission from the Heritage Committee, to sell the house to DAG. It was tough obtaining it, but we did." She adds that DAG had exacting standards in terms of the paperwork that it required from the family, papers that they didn"t have, owing to the fact that the house is old, the family is old, several family members had passed away, different papers were with different members of the family, and that the construction plans were washed away in the great floods that swept Calcutta in the 1960s. “The level of scrutiny was granular, and papers had to be obtained from various sources one by one."

However, despite the work involved, Arkamitra adds that “the family is ecstatic about the project and is committed to aiding DAG in whatever way possible to achieve its goal of creating a world-class museum, the first of its kind in the country".

For DAG, the challenges are of a different nature. “Jamini Roy has an emotional connect with the city and the people of Bengal, so we need to be mindful that any interventions we make will be in keeping with popular sentiment," says Anand. While he wants to retain the mood and provide an immersive experience of how Roy’s studio used to be, DAG will also need to bring in modern technology, air-conditioning, and free-flowing galleries that allow easy movement for museum visitors.

“We hope the museum will manage both and take Jamini Roy’s legacy forward in a way that would make him proud."

First Published: May 13, 2023, 09:30

Subscribe Now