Inside Royal Enfield's 'Studio' bet

How smaller-format Studio stores are helping Royal Enfield penetrate deeper into the hinterlands, and bounce back

It seemed like free fall. Five consecutive quarters of slide in growth till March this year meant Royal Enfield (RE) had its task cut out. The maker of the Bullet, Classic and 650 Twins, with a monopoly in the 250 cc to 750 cc segment of motorcycles in the country, was pulling out all stops to kick-start growth, including hunting for first-time buyers and nudging users to upgrade. RE sales had dipped from 8.22 lakh in FY19 to just under 7 lakh a year later. And then came the bolt from the blue: Covid-19 and the lockdown. All action stopped.

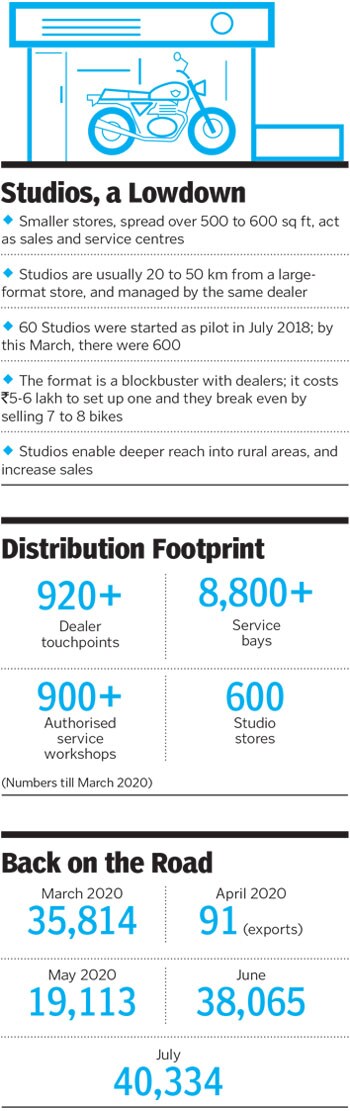

Fast forward to August 2020. The economy is on tenterhooks, the auto sector is attempting to scramble out of a tailspin, and the new normal in Covid-19 times is not year-on-year growth but month-on-month. From domestic sales of 32,630 units in March to zero in April (91 units were exported), 18,429 units in May, 36,510 in June and 40,334 in July. It’s a slow and steady climb from the bottom and if there’s one ace up RE’s sleeve in the current scenario it’s the Studio, the smaller-format sales and service stores—500 to 600 sq ft in size—that RE started opening in the hinterlands in July 2018.

In the first three months of 2020, RE added 100 such stores, taking the number to 600 till March 31. For perspective, RE has 921 large format-stores built over decades 600 in well under two years in non-urban India seemed a bit aggressive to a section of analysts. After all, the brand had acquired its iconic cult status due to its legion of bikers in urban India, although it first made a mark in rural India as it was considered a tough motorcycle on rough village roads. The more recent magical run for over a decade, however, was largely urban.If there was a method in opening Studio stores pre-Covid-19, that method assumed masterstroke proportions during the lockdowns. Vinod Dasari, CEO of Royal Enfield, decodes the concept of Studio. When the nationwide lockdown was lifted, Studios were the first RE stores to start doing business. “Just because we had opened all these stores, when volumes for everybody fell in May, ours fell the least,” Dasari said in an earnings call this June. Studios, he emphasised, helped to recover some of the volumes. The strategy, he added, of expanding beyond the cities seemed to be paying off.

Having tasted success, RE has been aggressively pushing Studios, taking the number to 674 by the end of July. Lalit Malik, chief commercial officer of RE, explains the commercial logic. The brand, which had its beginnings in rural India, is finally going back to its roots. Studios, he explains, help in expanding the footprint, and going deeper into the hinterland. For an aspirational brand, matching the aspirations of buyers in smaller towns made sense.

What also made sense was the low cost of expansion. At ₹5-6 lakh, Studios need about one-tenth the investment of a normal store. So the format can be replicated quickly across the country. The sweet spot for RE though is the per-store metrics. Just by selling seven or eight motorcycles, stores turn profitable. “Most of them have turned profitable,” Dasari claimed, explaining why going deeper into rural India is the need of the hour: 60 percent of the brand’s market is outside the main cities. “So we have to reach out to those people, otherwise they have to come to the city,” he added.

The Studio was not born solely to cater to rural demand. The need was also to make service centres accessible to buyers. What stumped the RE top brass was its low market share in regions where motorcycle growth was booming. The same motorcycle would find takers in other parts of the country but would struggle in some pockets. The reason was not hard to fathom: Accessibility to sales and services. So the company decided to focus on the markets where RE was lagging. While customers, says Malik, won’t mind traveling even 70 km to buy a motorcycle, covering the same distance for servicing it was a big problem. RE started Studios with a pilot of 60 stores in July 2018, and then it gathered steam.

The gambit worked, both with dealers and buyers. For Studios that were 20 km to 50 km from main stores, RE didn’t appoint a separate set of dealers. The existing ones were roped in. Take, for instance, Rajesh Mishra in Deoria, Uttar Pradesh, who has been selling REs since 2005. Last September, he set up two Studios in Rudrapur and Bhatpar Rani, both more than 45 km from the main showroom. Both the regions, Mishra explains, were not new. Over the last few years, he would send his employees to set up a canopy for

rural promotions. The frequency was three to four times a year, and the purpose was twin-fold: Making the brand familiar and accessible. With Studios, Mishra says, there is a permanent presence. “Both the Studios have been doing very well,” he says. [qt]The opportunityis quite large inrural areas, where there is money aswell as aspiration”

[qt]The opportunityis quite large inrural areas, where there is money aswell as aspiration”

Lalit Malik, chief commercial officer, Royal Enfield[/qt]RE, reckon auto analysts, has been smart to expand its footprint across rural areas. “It’s a good strategy of minimum investment and maximum returns,” says Amit Kaushik, managing director at Urban Science, a Detroit-based consulting firm. The Studio format, he says, is quite common with four-wheelers, but RE is the first one to experiment with it in the motorcycle space. Tackling three issues at a time—sales, service and convenience—Studios give RE the much-needed room to manoeuvre a prolonged slowdown, which has been made acute by the pandemic. The challenge for the brand now is not to go for senseless expansion. “How are they mapping the potential areas and customers would hold the key to future success,” Kaushik adds.

Malik, for his part, says that the brand is not reckless in moving into areas without any commercial interest there is enough headroom for expansion. If a jewellery brand like Tanishq, with an estimated average ticket size of ₹50,000-60,000, can have more than 1,400 stores, then it makes sense for RE as well. “We are in the motorcycle business, are an aspirational brand, and must have a wider presence,” Malik adds.

Studios, it seems, are well-timed and primed to help RE tide over the crisis till the economy and consumer sentiments improve.

First Published: Aug 20, 2020, 12:09

Subscribe Now