Coming from a family of sports fanatics from Dabolim in Goa, Rocky had started playing football as a child. Her mother was not in favour of it because she was concerned about Rocky getting hurt. “My brother was a football player. My father was also into sports and always encouraged me to take it up. But mom was difficult," she says. Rocky was 10 years old and in the fifth grade when she joined the Sports Authority of India academy in Margao, Goa. “I was an athlete there for ten years," she recollects.

In 1999, she started playing football professionally after her coach informed her about trials for the Goa state team. There was no looking back since then. Rocky represented India for six years between 2001 and 2007 and went on to become an established international player. Her transition from being a player in the national team to its head coach was not easy. She overcame many odds with hard work, perseverance and patience.

One of Rocky’s coaches encouraged her to consider a career in coaching. Rocky started with teaching football to kids in her locality. When she decided to take up courses related to coaching, she often found herself adjusting with male counterparts, with whom she had to travel during the courses. “There were very few women," she says. “It was difficult when I started, but a few fellow coaches were supportive. My parents were also supportive, but at times it was difficult to make them understand why I have do these courses with men."

After she received the required licences, Rocky was hired by the Goa Football Association in 2006. Six years later, she was chosen by the All India Football Federation (AIFF) for the national under-16 team. Gradually, she was shifted to the senior team. “The recognition from AIFF was huge since there were not many female coaches back then," she says.

The women’s national football team has outperformed itself ever since Rocky took over as head coach. India won the 2019 SAFF Women’s Championship under her guidance with a remarkable record of winning all four games, scoring 18 goals and conceding just one. The same year, they were also the reigning champions of the South Asian Games held in December.

According to Rocky, while the number of women working in and heading various departments in football federations is increasing, it is still a male-dominated space. “That stems from society. Even in our homes, it’s very much male-dominated and women have to fight for their own spaces. But things are changing for the better now." With conversations around equal pay gaining steam and access to more opportunities, Rocky believes that if women and girls passionately pursue their interests, “everything else will fall into place".

![]() Anuja Dalvi was the only female physiotherapist at the 2020 Indian Premier League

Anuja Dalvi was the only female physiotherapist at the 2020 Indian Premier League

Sports can be a powerful tool for social reform, according to Anuja Dalvi, who was the only female physiotherapist at the 2020 Indian Premier League (IPL). If women of all age groups are encouraged to participate in sports, there will be more conversations and activities among families that will in turn lead to a better gender balance, she believes.

“Sports is a demanding industry, with stressors like unanticipated schedules, irregular working hours, extensive travels, job insecurities and grinding physical work. This might make women think twice before entering the industry," says Dalvi, 35, who was assistant physiotherapist for the Rajasthan Royals team, and also in-charge of the Covid-19 task force set up during the IPL. “Traditionally, girls were restricted from participating in organised sports in our country and for me that reflects why we have less women in leading positions or roles," she says.

Over the last 11 years, Dalvi has worked with the National Cricket Academy, the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI), the Bangladesh Cricket Board, and the Pro-Kabaddi League as a central medical co-ordinator. She has also worked with coaches in cricket and feels some of the female coaches are far superior to some of their male counterparts. “Men have played and performed their best over centuries and hence we have more number of superior male athletes around us. So a general belief is that they are better coaches and administrators," she says. “Unfortunately, it is an extremely complex social equation and it will take years to reform."

Dalvi feels that the administrators must promote the right female talent in coaching and other fields and not just try to fill up quotas based on gender. “That, in my personal opinion, dilutes work quality and leads to strengthening the misbelief that men are better coaches compared to women," she says. ![]() Former under-19 player Disha Malhotra is currently classified as a UEFA C licenced coach. She has started a coaching centre for children called Foot and Ball in Delhi

Former under-19 player Disha Malhotra is currently classified as a UEFA C licenced coach. She has started a coaching centre for children called Foot and Ball in Delhi

There are also former players like Disha Malhotra, 29, who want to change things at the grassroots level. A former Indian women’s football team player (under-19) and presently classified as a UEFA C licenced coach, Malhotra founded a coaching centre called Foot and Ball in Delhi in 2015. It offers training programmes for children aged between three and 12.

Malhotra, who started playing football since she was 13 and in the eighth grade, often found that she was the only girl in a field full of boys. This meant she could not play in competitions on a regular basis. Yet, she managed to make it to the state team in Delhi and then represented India in the Asian Football Confederation Qualifying Championship in Malaysia when she was in her 12th grade.

Subsequently, she played in academies, clubs and leagues in Italy and the US. “I was a player for seven years," she says.

Malhotra then decided to go abroad to study sports management and get licences for international standard coaching. Apart from limited career scope as a football player, another reason she opted for coaching was chronic injuries sustained as a player. “I wanted to be a coach, but not this early. Destiny had other plans," she says, adding that when she started playing football as a kid, she could not see any other girl playing the sport. “At that time, football was not a sport for women in Delhi. No one told us it was an option," she says. Malhotra wants to change that for girls of today, by giving them and young boys interested in football access to the right kind of training.![]() Rituparna Roy represented Bengal in domestic cricket and became coach of India a later

Rituparna Roy represented Bengal in domestic cricket and became coach of India a later

Another player-turned-coach, Rituparna Roy, shares that her family wanted her to pursue an MBA because there weren’t enough opportunities in cricket. In 1995, ex-India player and selector Lopamudra Banerjee—Roy’s neighbour in Kolkata—saw her playing cricket in the locality with the boys. She made Roy an “awesome offer", and asked if she wanted to play professionally. “Lopa madam opened a camp just opposite my house where I could afford playing," Roy recollects. Her mother was supportive, but her father wasn’t because he felt she had no future in cricket.

Roy got selected for the sub-juniors when she was in the seventh grade, but her father did not let her pursue cricket professionally until she cleared class 10, and then class 12. “I waited for six years, but I did not leave cricket and practised every day in the camp. After finishing class 12, I finally participated in a state championship," she recollects. Roy went on to play in the Bengal state team.

“Thankfully, I played well and started getting recognition. My father was in awe of me after seeing my name in newspapers... that’s when he started supporting me." Roy also played for the India A team in 2008, and ten years later, went on to coach India A.

![]() Back in the late 2000s, however, uncertain about her long-term career prospects, Roy decided to study further. With an MBA from the IISWBM College in Kolkata, she took up roles in human resources and administration with corporates like PriceWaterhouseCooper for 10 years. During this time, she was offered an opportunity to coach.

Back in the late 2000s, however, uncertain about her long-term career prospects, Roy decided to study further. With an MBA from the IISWBM College in Kolkata, she took up roles in human resources and administration with corporates like PriceWaterhouseCooper for 10 years. During this time, she was offered an opportunity to coach.

“Don’t crib if you haven’t played for India. Do something where you can at least produce Indian players who can go and represent the country. That"s how I look at things," she says. That’s why when Roy was first offered the opportunity to coach the Odisha state women’s cricket team in 2010, she took it up. “In fact, my corporate experience helped, as they were looking for someone who is qualified and with a cricketing background," she recollects.

Roy has been coaching for 11 years, currently serving as coach of the women’s cricket team in Bengal. According to her, less women in coaching is a result of less female cricketers compared to male. “When the equilibrium will be balanced, we can talk about equal monetary structures and exposure. We also need to understand that in an Indian home, a boy is sent to the ground to play and a girl is sent to music school. The change has to come from the family. Parenting is important." Roy is optimistic and confident that with so many changes happening, everyone will see more women as coaching staff in the coming years. “I"m sure in the near future you may also see a woman coaching a men"s team."

Shantha Rangaswamy, the first woman to lead an Indian cricket team and the first female recipient of the Arjuna Award, has different views. She believes that despite efforts to improve gender diversity in support staff for women"s teams, even players seem to want male coaches. This results in many qualified female coaches not getting opportunities, leading to overall declining interest and frustration. “Unless the mindset of people, administrators and players changes, women coaches and support staff are bound to play second fiddle... the trend will continue for the next couple of decades."

![]() Shantha Rangaswamy is the first woman to lead an Indian cricket team. She also served as coach of the Indian team and selector. The Arjuna Awardee is now on the BCCI Apex Council Image: Anshuman Poyrekar Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Shantha Rangaswamy is the first woman to lead an Indian cricket team. She also served as coach of the Indian team and selector. The Arjuna Awardee is now on the BCCI Apex Council Image: Anshuman Poyrekar Hindustan Times via Getty Images

The first woman to receive a lifetime achievement award from the BCCI, Rangaswamy captained 12 of the 16 Tests she played since making her debut in October 1976. Even after calling it a day as a player, she remained active in women’s cricket, serving as coach of the Indian team before becoming a selector. Rangaswamy, 67, currently a member of the BCCI Apex Council, also points out that no one talks about the gender pay gap in cricket.

“Take BCCI, for instance, where male selectors get ₹80-90 lakh, while women selectors get only ₹25 lakh. For BCCI, 90 percent of revenue comes from men"s cricket, so women’s cricket doesn"t generate enough revenue to match the expectations of female players and coaches," she says, adding that female coaches have achieved as much, if not more, than their male counterparts. “In 2005, even before BCCI came into the picture, we were runners up in the World Cup and the coach was a lady. In 2014, a lady coach steered the team to victory in the quadrangular also comprising New Zealand, Australia and England. We were winners. There is so much hype about a male coach that the players get carried away."

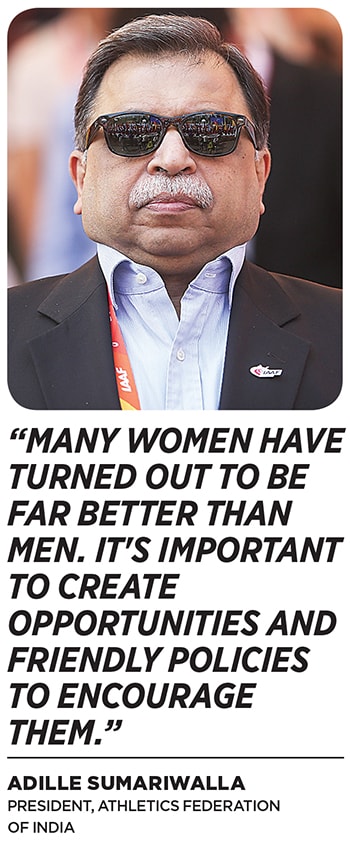

According to Athletics Federation of India (AFI) President Adille Sumariwalla, there is a dire need to promote representation of women in sports. “We need to create a pipeline for them. In fact, many women have turned out to be far better than men. The important thing is to create opportunities and friendly policies to encourage them," he says, adding that given that women usually have a larger share of domestic work at home compared to men, the pressure is always higher than male sportspeople. AFI is working to include more women in its technical staff, which is currently male dominated. From the coming season, there will be 20 percent women technical officials, which will gradually be increased to 50 percent over the next three years.

Dalvi stresses on the need to build systems to encourage and support the right female talent at the grassroots, instead of just creating reservations or quotas for women. “It’s time to correct the mistakes our ancestors made, isn’t it?"

Maymol Rocky played for India for six years. She then became the first female head coach of the national football team

Maymol Rocky played for India for six years. She then became the first female head coach of the national football team Anuja Dalvi was the only female physiotherapist at the 2020 Indian Premier League

Anuja Dalvi was the only female physiotherapist at the 2020 Indian Premier League Former under-19 player Disha Malhotra is currently classified as a UEFA C licenced coach. She has started a coaching centre for children called Foot and Ball in Delhi

Former under-19 player Disha Malhotra is currently classified as a UEFA C licenced coach. She has started a coaching centre for children called Foot and Ball in Delhi Rituparna Roy represented Bengal in domestic cricket and became coach of India a later

Rituparna Roy represented Bengal in domestic cricket and became coach of India a later Back in the late 2000s, however, uncertain about her long-term career prospects, Roy decided to study further. With an

Back in the late 2000s, however, uncertain about her long-term career prospects, Roy decided to study further. With an  Shantha Rangaswamy is the first woman to lead an Indian cricket team. She also served as coach of the Indian team and selector. The Arjuna Awardee is now on the BCCI Apex Council Image: Anshuman Poyrekar Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Shantha Rangaswamy is the first woman to lead an Indian cricket team. She also served as coach of the Indian team and selector. The Arjuna Awardee is now on the BCCI Apex Council Image: Anshuman Poyrekar Hindustan Times via Getty Images