5 Indian deeptech startups changing the auto industry with new tech and modern

From SimYog to CynLr and Mihup, these deeptech startups are innovating at high speed to supercharge India's automotive industry

India’s deeptech startup landscape has a growing number of ventures that are targeting both Indian and the world’s biggest auto OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) as customers. They are developing technologies and building products highly relevant across multiple stages of the supply chain—from upstream phases within manufacturing all the way to end-user customer experience.

These technologies include AI (artificial intelligence)- and machine learning-based software simulation of the semiconductor chips and electronics that go into modern cars, semi-humanoid robots that can make assembly more efficient, embedded virtual assistants to assist drivers, innovations in EV (electric vehicles) cell chemistry, and low carbon emission techniques to recycle end-of-life battery cells in the EV sector. Here are snapshots of five such companies.

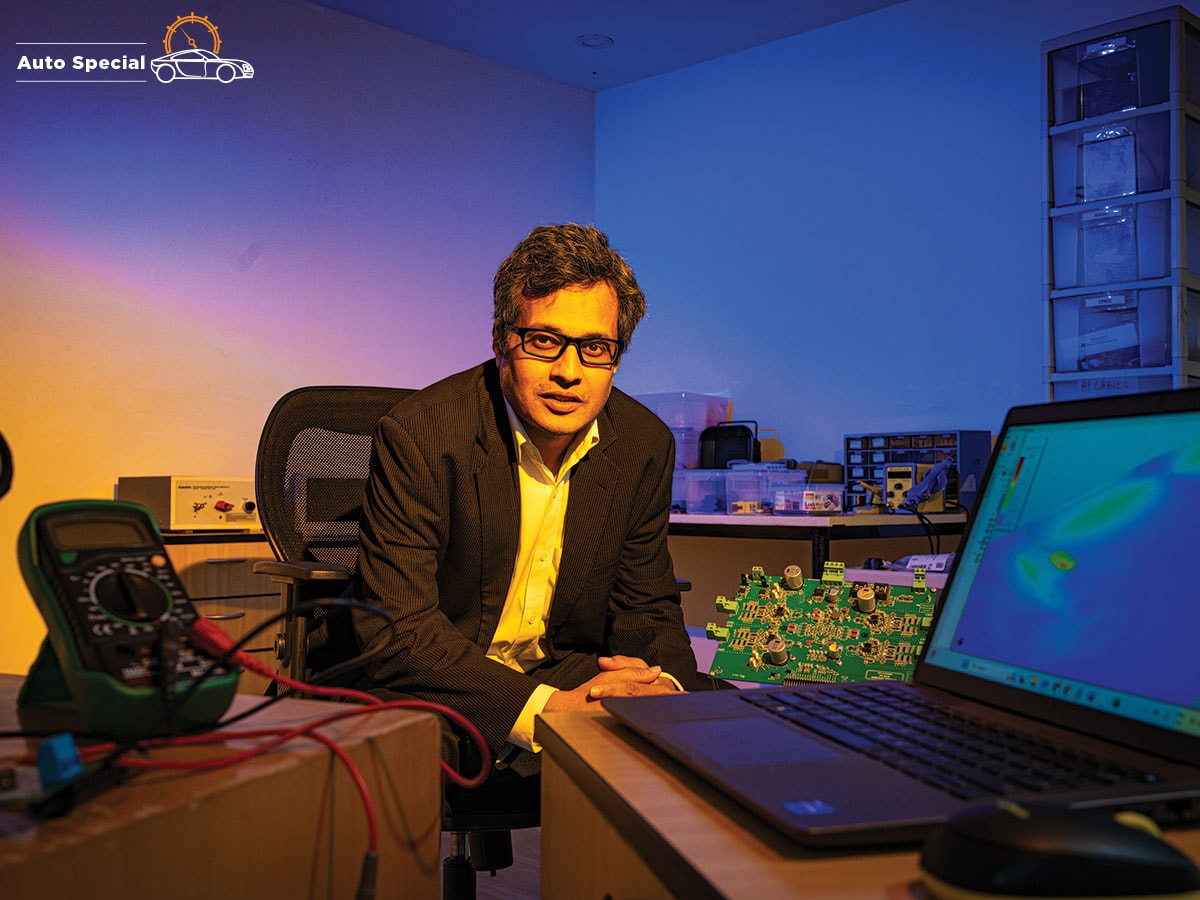

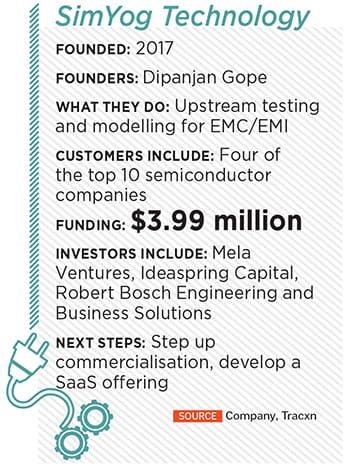

Professor Dipanjan Gope at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) has been working on electromagnetic solvers for nearly two decades. And SimYog is his second startup to find commercial applications of the science that’s dear to him. The name, as you might have guessed, is a play on ‘simulation’ and the Sanskrit word ‘yog’ which means ‘the practice of’.

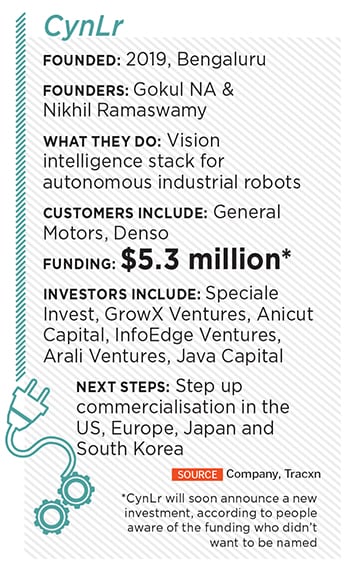

And that’s where SimYog’s innovative products are deeply relevant to the automotive industry. The context is that “today’s cars are nothing like those of 10 years ago", Gope points out, with the proportion of the electronics in them going up with each iteration. Even fossil-fuel-burning vehicles can have upwards of 30 percent of their make-up accounted for by electronics, he says.

Therefore, problems such as electromagnetic interference are very real. There are documented instances such as unintended and uncontrolled acceleration of a car or headlights switching off as the car passes a cell tower and so on, owing to such problems.

Therefore, problems such as electromagnetic interference are very real. There are documented instances such as unintended and uncontrolled acceleration of a car or headlights switching off as the car passes a cell tower and so on, owing to such problems.

What SimYog offers is a sophisticated software simulation product that helps auto engineers simulate the behaviour of various electrical and electronic components much earlier in the design, testing and manufacturing cycle than are done today. And complementary to the software simulation product that SimYog offers is a machine learning-based data model.

“What we want to do is front-load the analysis, meaning make it possible much earlier in the design stage," Gope tells Forbes India. “You not only solve the safety risk, but you also solve time-to-market issues and bill-of-materials issues."

Together, with the simulator and the database, SimYog’s solution allows customers to both make models of various components and run measurements of various parameters.

Of SimYog’s two software products, one is for testing at the tier-one level called Compliance Scope and the other is for testing at the vehicle level called SEMScope. Both the products have a physics engine, the solver engine, with the capability of inputting the measurement data and generating a model, and a solver engine capability.

On the commercial front, “all our customers are Fortune 100 companies. Today we have four of the top 10 semiconductor companies, three of the top 10 tier-one companies and a very giant OEM", Gope says.

On the commercial front, “all our customers are Fortune 100 companies. Today we have four of the top 10 semiconductor companies, three of the top 10 tier-one companies and a very giant OEM", Gope says.

Gope graduated with a BTech degree from IIT-Kharagpur in 2000 and earned his PhD from the University of Washington in 2005. He returned to India in 2011 and joined IISc in 2014, where he is an associate professor in the department of electrical communication engineering.

His previous startup, Nimbic, was acquired by Mentor Graphics. And German auto components giant Robert Bosch is a partner to the research at IISc that helped start SimYog, he says.

Last year the company, with a team of 35 scientists and engineers, hit close to $1 million in revenues and SimYog aims to hit $10 million in sales over the next two-and-a-half years, he says. Currently the business model is around licensing the software products for on-premises deployment. SimYog is in the early stages of working on a software-as-a-service option. For now, the auto industry is the primary focus of the venture, but the tech being developed at SimYog is also relevant to aerospace, industrial electronics and medical electronics.

(From left) Nikhil Ramaswamy and Gokul NA founded CynLr in 2019Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

(From left) Nikhil Ramaswamy and Gokul NA founded CynLr in 2019Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

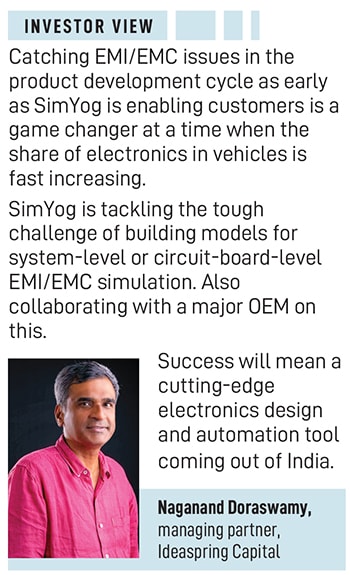

Gokul NA and Nikhil Ramaswamy opened CynLr (short for Cybernetics Laboratories) to the market in January—they’ve persevered for close to 10 years to get here. At the heart of their products is their proprietary tech that guides industrial robotic arms to mimic how humans would use their arms and fingers guided by their eyes.

Their products and technologies include CyRo, a multi-purpose, semi-humanoid, reusable visual robot platform and Vision, CynLr’s vision object intelligence stack.

Their products and technologies include CyRo, a multi-purpose, semi-humanoid, reusable visual robot platform and Vision, CynLr’s vision object intelligence stack.

Guided by Vision, CyRo is a multi-arm robotic manipulator that can grasp objects—it has never seen before and under extreme variable lighting conditions—with literally no training. It requires no lighting engineering and can handle complexities like reflective objects such as transparent/translucent packaging, the entrepreneurs explain.

So far, CynLr has secured $1 million in orders with $600,000 in billings, as of September. The deeptech entrepreneurs expect to hit revenue of $3 million in 2025, Gokul says.

Among CynLr’s customers are some of the world’s biggest auto OEMs and Tier 1 suppliers.

To step up their operations, on September 26, CynLr opened its first international R&D lab, in Switzerland. CynLr has established its first research collaboration with"¯CSEM, the public-private Swiss tech innovation centre. Through this partnership, CynLr will work on advanced compute capabilities for its Vision product.

“There is a resonance between our work and the fundamental research being done there in areas such as material science, computer vision and robotics," in two of the top universities there, EPFL in Lausanne and ETH in Zurich, Gokul says. “And it is also in close proximity to European customers and their warehouses in Germany, France and Italy."

CynLr has also received its first tranche of"¯Swiss federal funding. And the company has secured $9.25 million in fresh funding, it said in its September press release, announcing the Swiss R&D lab’s inauguration. The company plans to use the money to expand its R&D by"¯25 more robots across its centres in Switzerland, India"¯and the US.

On the manufacturing front, the company is increasing capacity to support"¯sales of about 50 CyRo systems a year to meet the current order pipeline. This also translates to overall capacity for"¯60 to 100 robots a year. Gokul expects there’s scope to grow revenues to $2-3 million for 2025 from about $1 million this year and the company is targeting $12 million in 2026.

At around $18 million, CynLr will break even and that will also allow the company to sustain R&D at about 20 percent, says Gokul. Customers who’ve already bought a CyRo system or are in advanced stages of evaluating it are General Motors in the US, Japanese auto components maker Denso and industrial equipment giant Doosan in South Korea. “After proof of technology, it’s now proof of business for us, and then comes scaling," Gokul says.

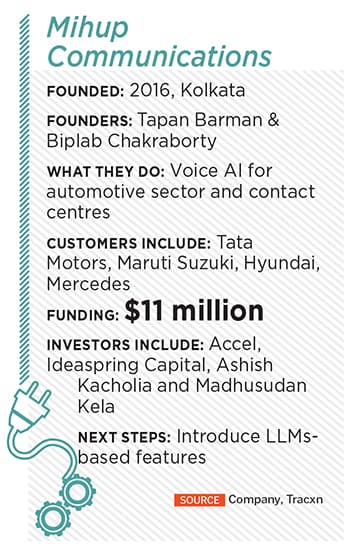

(From left) Biplab Chakraborty and Tapan Barman, co-founders, Mihup Communications Image: Subrata Biswas for Forbes India

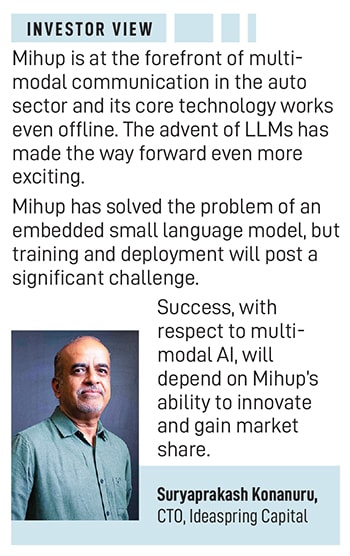

Mihup’s co-founder Tapan Barman speaks a dialect called Kantapuri, “which as you know isn’t among the 24 main languages in the country," and that’s the origin of how the startup was founded, he says: Making tech accessible to people irrespective of what they speak in a country of some 800 languages, is the ambition.

More narrowly, as a commercial for-profit venture, Mihup’s founders, including Barman’s childhood friends Biplab Chakrabarty and Sandipan Chattopadhyay, have focused on a virtual platform that helps people use natural language to interact with machines, and in particular with cars.

More narrowly, as a commercial for-profit venture, Mihup’s founders, including Barman’s childhood friends Biplab Chakrabarty and Sandipan Chattopadhyay, have focused on a virtual platform that helps people use natural language to interact with machines, and in particular with cars.

Tata Motors is the company’s biggest customer in the automotive space, while Mihup’s tech is also applicable in contact centres and various internet-of-things use cases.

“Think of it like an Alexa inside the car," Barman says. “We are on the journey of building an operating system to simplify human-machine interaction." In the automotive sector, Mihup’s product, called AVA (short for automated virtual assistant), is an embedded (built-in) virtual assistant in the car, which helps users control various functions via natural language commands.

For example, “if you say ‘Hey AVA I am feeling hot, can you do something?’ your virtual assistant will interact with you and ask about your preferred temperature," he says. Then there are of course music controls, but also the ability to get functions like rolling down a window or opening the sunroof in a handsfree manner, by asking AVA, he says.

“We are the default voice assistant in all Tata vehicles that you see on the road. We have rolled out more than 10 lakh vehicles with Mihup assistant, and we are doing about 40,000 vehicles month on month."

Initially, the assistant was fully embedded which meant that one didn’t need an internet connection. It was a factory-installed software and everything was happening within the electronics available inside the vehicle. Today, that’s expanded to include functions and experiences that are possible if an internet connection is available.

Initially, the assistant was fully embedded which meant that one didn’t need an internet connection. It was a factory-installed software and everything was happening within the electronics available inside the vehicle. Today, that’s expanded to include functions and experiences that are possible if an internet connection is available.

Asking AVA to play a song from Spotify, is an example. Launched to support English and Hindi, AVA now supports more than 10 languages. In the foreseeable future, it will also be able to provide drivers with location-based useful information and other such services. On a long drive, coming up, a good place to eat with high ratings for cleanliness, is an example.

“And we are going to introduce LLM in the vehicle itself," Barman tells Forbes India. “The idea is that can we introduce interactions where the virtual agent becomes more proactive rather than reactive and users will be able to experience ChatGPT-like conversations."

While Barman declined to comment on customers for this, Mihup is “close to engaging with the number one volume maker in the country," a person with direct knowledge of the partnership told Forbes India.

Mihup also counts Hyundai and Mercedes among its customers.

For the technically curious, AVA is available as an SDK (software development kit) to tier-1 vendors, Barman explains. Therefore they can install it in their products—companies such as Harman, Vestion and Robert Bosch are examples —and supply it to the OEMs.

As we go to print, Mihup will also have announced a new round of funding, with an investment of ₹50 crore, which will help them expand their operations overseas and recruit experienced people to bolster its current team of 60.

In FY24, Mihup’s revenues were about ₹24 crore, with an EBITDA of close to 30 percent, Barman says. “And we are pretty much on track to achieve ₹200 crore revenue in the next 24 months."

Rajat Verma’s Lohum Cleantech is making an overseas production forayImage: Amit Verma

Rajat Verma’s Lohum Cleantech is making an overseas production forayImage: Amit Verma

Rajat Verma and his MBA-mate Justin Lemmon started Lohum some six years ago with a plan to recover critical materials in the EV battery supply chain via recycling. The sector was nascent in India at the time, and Lohum was one of the first commercial attempts in the country to recover materials including lithium, cobalt, and nickel by recycling the individual cells that make up an EV battery.

Today the company is a full-fledged operation that’s also making an overseas production foray, and going beyond EV batteries. It’s also beginning to expand its target portfolio of recoverable materials to include platinum, palladium, aluminium, copper, neodymium and so on. There are some 30 minerals included in a list of “critical" minerals by the government, as these are vital to industries including semiconductors, healthcare, and advanced electronics.

Today the company is a full-fledged operation that’s also making an overseas production foray, and going beyond EV batteries. It’s also beginning to expand its target portfolio of recoverable materials to include platinum, palladium, aluminium, copper, neodymium and so on. There are some 30 minerals included in a list of “critical" minerals by the government, as these are vital to industries including semiconductors, healthcare, and advanced electronics.

“All these critical minerals, by their very definition, are very geopolitical in nature, and almost 90 percent of their refining activities take place in China," Verma tells Forbes India in an interview. “So, that’s the core capability that we are trying to build here in India."

That means developing the knowhow to actually refine critical minerals in India and create value-added products from those critical minerals locally. Today Lohum has India’s largest capacity—at 4GWh equivalent—to recover such materials for reuse, Verma says. And the company is in the process of doubling that capacity.

Lohum has set up a pilot plant for cathode active materials for the nickel-manganese-cobalt configuration, in the Delhi NCR region, where the company is headquartered. It’s recently announced a plan to build a larger commercial facility in Krishnagiri in south India.

This plant will extract materials from both NMC and LFP cathodes of battery cells. LFP stands for lithium iron phosphate. NMC and LFP are two well-known configurations of the cathodes in the battery cells. In simple terms, in battery cells, there are cathodes which accept electrons or ions (think of them loosely as units of electric charge) and anodes that give the charges out.

This plant will extract materials from both NMC and LFP cathodes of battery cells. LFP stands for lithium iron phosphate. NMC and LFP are two well-known configurations of the cathodes in the battery cells. In simple terms, in battery cells, there are cathodes which accept electrons or ions (think of them loosely as units of electric charge) and anodes that give the charges out.

And depending on the vehicle or other purposes for which the batteries are used—energy storage is another common use case—batteries can have thousands of cells. And the cells don’t degrade evenly with use.

Lohum has built the in-house capability and established the supply-chain connections to take in these cells, check their current state of repair, repurpose ones that still have enough juice by making “second-life" batteries, and recycle the ones that are used up.

The company also provides some ancillary services to the EV sector, including software solutions to the fintech and the insurance companies which need to understand the residual value of the batteries “Extended Producer Responsibility Services," to the OEM (original equipment maker—like car and two-wheeler makers) market to support their sustainability responsibilities and a “battery price index".

An important next step is a joint venture that Lohum has just announced to set up a plant in Indianapolis, in the US, with two partners—Re-Element Technologies and American Metals. Lohum will do a first level of processing there before shipping the scrap to India for final refining. Similarly, the company has an exclusive 100 percent offtake agreement with a customer in the UK.

“Lohum is one of the most under-the-radar exceptional companies, steadily gaining national recognition," Ishpreet Singh Gandhi, founding managing partner at Stride Ventures, says, who’s been an early backer of Lohum, with commitments of ₹150 crore over the last three years. “What stands out is their business model—it’s not just innovative, but immensely scalable."

Overall, Lohum closed last financial year at about ₹535 crore in revenue, and is on track to hit at least ₹840 crore this year, while Verma would like to finish closer to ₹1,000 crore. “We expect to maintain a 70-80 percent CAGR over the next 4-5 years," he says.

He also expects the company, which has about 1,000 employees, to maintain its profitability, which was at 18 percent EBITDA (excluding ESOPs) for FY24.

(Left to right) Pankaj Sharma, Kartik Hajela and Akshay Singhal co-founded Log9 in 2015 Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

(Left to right) Pankaj Sharma, Kartik Hajela and Akshay Singhal co-founded Log9 in 2015 Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

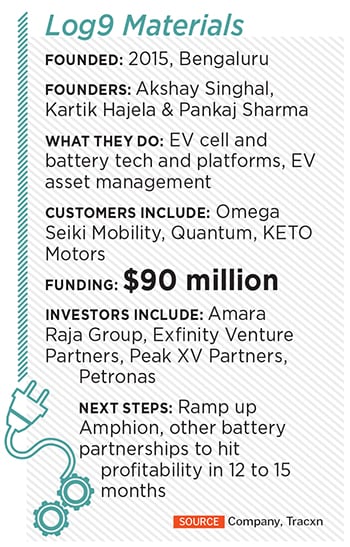

The year 2024 has been one of milestones and change for the founders of Log9 Materials, India’s first commercial EV (electric vehicles) battery cell manufacturer. For one, working on core cell chemistries and technologies, and battery platforms gave them the technical capability to tap an adjacent area and start an entirely new services business.

They announced the formation of Amphion, an EV asset management business, in April. This is a sort of upgraded full-stack avatar of the company’s Log9 Mobility division. Today Amphion helps customers ranging from Delhivery to Ikea keep their EV batteries in good repair, tapping the fairly sophisticated battery analytics platform that Log9 has developed.

They announced the formation of Amphion, an EV asset management business, in April. This is a sort of upgraded full-stack avatar of the company’s Log9 Mobility division. Today Amphion helps customers ranging from Delhivery to Ikea keep their EV batteries in good repair, tapping the fairly sophisticated battery analytics platform that Log9 has developed.

“The biggest thing for us is that we have been able to go quite deep on our whole battery analytics platform," co-founder and CEO Akshay V Singhal tells Forbes India. “We have been able to create an AI (artificial intelligence model-based platform where we can collect battery data from manufacturing to in-field usage to predict efficiency of usage."

Log9 now has physical service centres and over 100 technicians who now service business customers’ EVs, with a deep understanding of the behaviour of different batteries and cells in different operating conditions.

“See, nobody wants to pay for (just) knowing there’s something wrong," Singhal points out, therefore selling the software platform itself like a SaaS product, for instance, doesn’t work. What Log9’s invested in is to actually build a brick-and-mortar service to multiple types of customers.

The tech that underpins this service has multiple facets. First is Log9’s deep understanding of how batteries and cells behave under different conditions, built up over several years.

Second is their ability to collect and analyse manufacturing data in terms of what kind of cells have gone together to make a battery pack and what has been the performance of the battery pack at the time of manufacturing and so on.

The third layer is in-field data on a battery’s behaviour in real conditions, how fast or slow it was being charged, how the driver was using it, current, voltage and temperature data in deployment and so on.

“So the architecture to collect and analyse all this data, and then run AI models on top of it is the underlying tech," Singhal says.

The white space that Log9 found was as follows, according to Singhal: There have been premature failure of electric vehicles and batteries. And “a lot of defaults have happened" on the EV loan repayment front. Buyers, such as fleet operators or logistics services providers, expected a certain level of operational efficiency that didn’t materialise owing to a mixture of issues.

Such challenges range from access to the right financiers to the right charging stations, and servicing and maintenance providers. The combination has “led to increased risk of financing EVs, inefficiency in utilising EVs and that is delaying the whole electrification journey of last mile logistics" in India, he says.

Cell manufacturing and battery packs capabilities are being ramped up primarily via their partnership with Amara Raja Group, their biggest investor. Log9 is expanding its partnerships, including with Japan’s Musashi Seimitsu Industry, which was announced in September.

The two companies will collaborate on EV powertrain technology, integrating Musashi’s e-Axle systems with Log9’s advanced battery solutions. This collaboration targets performance improvements and energy efficiency for electric two-wheelers and three-wheelers, addressing urban energy management challenges. Aimed at OEMs in India and globally, the partnership will also implement a centralised service model for quicker repairs.

As to its own plans, “Log9 is not putting up its own Giga factory, while we do remain partners with Amara Raja in terms of their plans of setting up a factory", Singhal says. And Log9’s existing 50MWh capacity pilot plant is being used for R&D and collaborating with customers on specific needs, he adds.

Overall, at the consolidated Log9 level, including Amphion, the venture made revenue of ₹110 crore in FY24. Singhal expects “a minimum of 2x growth" in the current fiscal, and to hit profitability over the next 12 to 15 months.

First Published: Oct 25, 2024, 16:30

Subscribe Now