The patriarch, though, put a stiff and almost improbable pre-requisite. “Feel free to join when you start earning Rs3 lakh per month," he said. The intent was to dissuade the young lad. Remember, underlined his father, the amount earned must be sufficient to raise your family in the same comforts and standard in which you have been raised. The seventeen year old, however, earnestly picked up the gauntlet. In the 90s, it was nothing less than a fantasy for an undergrad to even dream of earning lakhs in salary.

So Bahl joined a Singapore-based merchant navy firm, continued his studies amidst ferries, tankers, and containers, and self-funded his long-distance correspondence education from the job that he was pursuing simultaneously. By 2002, he was earning Rs3 lakh per month, thanks to his exceptional performance, which led to a couple of out-of-the-turn promotions. His father kept his promise, and the 22-year-old joined Fun Foods—the family business of manufacturing and marketing processed foods such as oriental salads, mayonnaise, pizza toppings and spices—in 2002. Over the next six years, the company made heady progress.

Then came 2008, and the cookie crumbled. “Please don’t sell the company," the son pleaded. Fun Foods was to be acquired by German packaged food company Dr Oetker for Rs110 crore. For a Rs28-crore company that was started in 1983 by husband-wife duo of Rajiv and Vibha Bahl, getting an almost four times’ return was nothing less than spectacular.

“Please don’t sell it," the son implored passionately. “I want to build and scale this company." “Viraj," the father tried to make his son see reason, “my legacy is to ensure that my kids have enough and don’t have to go through the hardship I did."

The father was generous enough to give Bahl his share from the sell-out deal. “This is your kitty. Do whatever you want to do," he underlined. Bahl worked with the new owner for a year, and then gave in to his entrepreneurial instincts. From the food processing business, he switched to foods’ business, and opened a chain of restaurants in 2009. The biggest one, Bahl recounts, was a 150-seater in the bustling Lajpat Nagar market, just seven kilometres from the heart of Delhi.

Over four years later, in 2013, Bahl found himself in a pickle. Pocket Full was never houseful, restaurants stayed empty and naked, and Bahl was a failed entrepreneur. What aggravated the pungent smell of failure was the fact that the second-generation founder didn’t have a single penny. While a chunk of the money that he got from his father was used to buy a house, the remaining amount was invested in the restaurants.

With zero money in his pocket, Bahl took a risky gambit. His wife allowed him to sell the house, and Bahl decided to go back to the food processing business. He bought a small plot of land at Neemrana, Rajasthan, some 90 kilometres from Gurugram, Haryana, and started Veeba.

The vision for the second innings was crystal clear. First, Veeba would be a professional organisation with no family connection. Second, Bahl took a B2B route and shielded Veeba from the retail heat of domestic and foreign rivals. Third, the founder zeroed in on niches in sauces and condiments to make a mark. “We didn’t want to be a me-too product," he says. In six months, the 35,000 square feet land at Neemrana was converted into a factory on a war-footing. The homegrown gladiator was now ready to conquer the world with a killer product and his infectious smile.

![]()

Six months down the line, deep frown lines engulfed a smiling face. People were hired, the factory was ready, ketchup and mayonnaise was being produced, but there was negligible demand. "The first year was the most difficult period of my life," contends Bahl. “It was even worse than the restaurant failure."

He explains why. Veeba needed big orders to keep the machinery oiled and running. The orders, however, trickled only in small numbers. Bahl exhausted all the money, the prospect of defaulting on salaries started haunting him, and what followed next was weeks and months of sleepless and erratic nights. Ten days leading to the seventh of every month—the day when the salaries were credited—were most traumatic. “I would wake up at 3 am, and think what would happen if I failed to pay the salaries," he recounts.

If the nights were distressing, then the days were equally agonising. Bahl used to spend hours at the offices of QSR (quick service restaurant) companies. From early morning till late afternoon, he used to stay put at the reception of a bunch of big players including Domino’s, but he failed to crack any meeting with the top brass.

![]()

The post-lunch hours were spent fanning across the market, and trying to grab whatever orders he could. The ritual went on for months. While the big players remained cold, venture capitalists too declined to play ball. For an entrepreneur who was fast running out of money, and who had led and scaled the family business not so long ago, it was distressing to find no takers.

Then came a ray of hope. Deepak Shahdadpuri of DSG Consumer Partners, an early-stage venture capital firm, made his first bet on Veeba in 2013. The money was enough for Bahl to tide over the crisis. Three months later, he had a lot on his plate.

Bahl got an order of 70 tonnes of supply from Domino’s. This was followed by Pizza Hut, Taco Bell, KFC, and other QSR outlets placing orders. Veeba’s story progressed over the next few months, but a year later, it started to lose steam again. The business was progressing well, but it needed more capital for investment, expansion and operations. Shahdadpuri could sense the unease that had been bothering the founder for weeks.

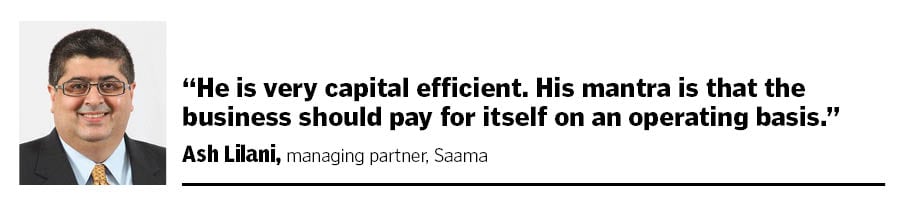

![]() In 2015, lady luck smiled on Bahl. He was having lunch with Shahdadpuri at a restaurant in South Delhi. The investor started the conversation. “You are not doing anything wrong," he tried to explain to the founder who was under tremendous stress. “Your problem is money." He took a tissue paper lying on the table, scribbled a few lines and numbers, took the consent of the struggling founder and wired a cheque of $1 million in 24 hours. “It was a contract signed on a tissue paper," recalls Bahl, adding that the bridge round of funding was the last time Veeba raised money from a position of distress. Three years later, in 2018, Veeba reportedly raised $6 million from Verlinvest, a private Belgian family investment company, and existing investors such as DSG and Saama Capital. By FY19, the company managed to take its operating revenue to Rs239 crore, and had a loss of Rs17.4 crore.

In 2015, lady luck smiled on Bahl. He was having lunch with Shahdadpuri at a restaurant in South Delhi. The investor started the conversation. “You are not doing anything wrong," he tried to explain to the founder who was under tremendous stress. “Your problem is money." He took a tissue paper lying on the table, scribbled a few lines and numbers, took the consent of the struggling founder and wired a cheque of $1 million in 24 hours. “It was a contract signed on a tissue paper," recalls Bahl, adding that the bridge round of funding was the last time Veeba raised money from a position of distress. Three years later, in 2018, Veeba reportedly raised $6 million from Verlinvest, a private Belgian family investment company, and existing investors such as DSG and Saama Capital. By FY19, the company managed to take its operating revenue to Rs239 crore, and had a loss of Rs17.4 crore.

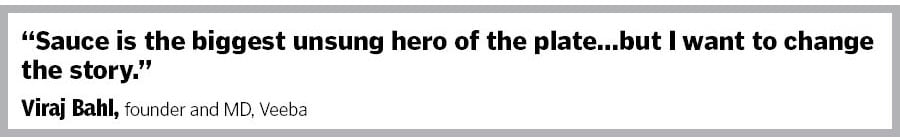

Fast forward to September 2023. Veeba has leapfrogged to Rs811 crore in FY23, posted a loss of Rs0.5 crore, and is striking a revenue run-rate of over Rs1,000 crore for FY24. The biggest plus is the fact that it has emerged as the biggest homegrown sauce and condiments brand in India (see box).

There is another plus for the company: Just eight percent of the revenue comes from B2B channels, and 92 percent sales is through retail. Veeba, maintains Bahl, has a presence across 700+ cities, a distribution network of 1.5 lakh retail points, and over 80 stock-keeping units (SKUs) spread across 14 categories. While the top sellers include eggless mayonnaise, chef special tomato ketchup, tandoori mayonnaise, garlic mayonnaise and schezwan chilli chutney, the company recently rolled out cooking sauces and "Woktok" range of masala Chinese for the Indian palate.

Bahl’s plan now is to make Veeba much more than a sauce company. The brand will launch one new range over the next four years. “By 2028, Veeba should have four more brands and a presence across seven categories," he says. The game-plan, he adds, is to make Veeba a consumer goods’ company. “It won’t be confined to sauces," he says. “It can be more ketchups, biscuits or other products," he says, declining to disclose more on the future product pipeline and launches.

![]()

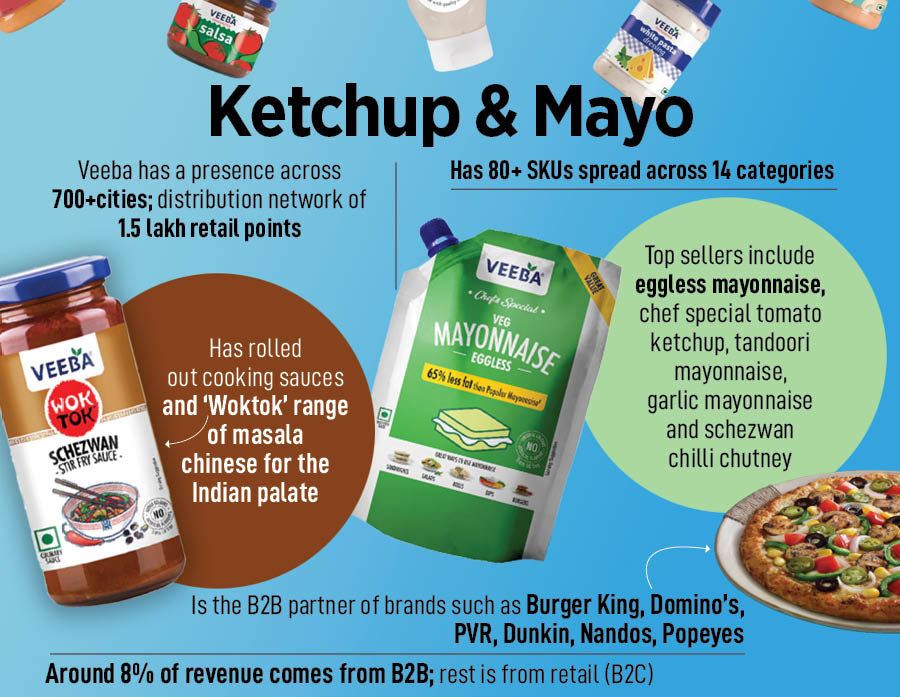

Backers are delighted with the progress of the sauce maker. “He is immensely capital efficient," says Ash Lilani, managing partner at Saama. He has run a tight ship, has innovated to stay ahead of the curve, and believed in the mantra that a business should pay for itself on an operating basis.

The philosophy that one should only raise equity for two things—either for capacity expansion or new product launches—has done wonders for the founder. From taking a B2B route to stabilise and consolidate the business, picking up categories where he is not taking the rivals head-on and establishing a wide distribution network which can later on be used to funnel more products, Bahl has taken years to build his sauce empire. The only challenge for the founder, Lilani says, would be to be wary of brands who might play price warriors, take losses and gain volume market share. “But that’s something you can’t control," he says. What Bahl has firmly under his control, though, is the quality and the desire to play a long game.

Bahl reckons that his challenge would be to keep growing sustainably. As he expands his empire and adds more items to his gravy train, the chances of losing a sharp focus from the bottom-line is realistic. The learning from a failed product launch—in 2019, Veeba entered the child nutrition segment with V-Nourish, and had to pull the plugs in 2021 after taking a loss of Rs 70 crore—should also be a reminder to the perils of a realistic possibilities of floundering in a few segments. Bahl, though, prefers to look at the learning and not mistakes.

The biggest learning, he underlines, is giving too much importance to hustle. “It’s an abused word, and is helpful in the formative years of entrepreneurial journey only," he underlines. The company, he lets on, started doing well when he started hiring people who were better than him. “Leave hustle at the right time or else hustle will eat you alive," he says, sharing his other learning. “Though frugality is good, staying too frugal might be counter-productive," he explains, adding that it’s tricky to understand the nuances and know when the lines get blurred. The trickiest thing, though, is to understand the nature of the sauce business. “Sauce is the biggest unsung hero of the plate," he says. It takes years of patience, innovation, failures, hits and misses to come up with a secret recipe. Burgers, sandwiches and pizzas, he underlines, fascinate consumers because of the bun, bread, crust and ingredients. But what makes them a massive hit is the sauce. Otherwise, it’s bland. “It"s tricky to sell the story of an unsung hero. But I am trying to script a blockbuster," he smiles.

In 2015, lady luck smiled on Bahl. He was having lunch with Shahdadpuri at a restaurant in South Delhi. The investor started the conversation. “You are not doing anything wrong," he tried to explain to the founder who was under tremendous stress. “Your problem is money." He took a tissue paper lying on the table, scribbled a few lines and numbers, took the consent of the struggling founder and wired a cheque of $1 million in 24 hours. “It was a contract signed on a tissue paper," recalls Bahl, adding that the bridge round of funding was the last time Veeba raised money from a position of distress. Three years later, in 2018, Veeba reportedly raised $6 million from Verlinvest, a private Belgian family investment company, and existing investors such as DSG and Saama Capital. By FY19, the company managed to take its operating revenue to Rs239 crore, and had a loss of Rs17.4 crore.

In 2015, lady luck smiled on Bahl. He was having lunch with Shahdadpuri at a restaurant in South Delhi. The investor started the conversation. “You are not doing anything wrong," he tried to explain to the founder who was under tremendous stress. “Your problem is money." He took a tissue paper lying on the table, scribbled a few lines and numbers, took the consent of the struggling founder and wired a cheque of $1 million in 24 hours. “It was a contract signed on a tissue paper," recalls Bahl, adding that the bridge round of funding was the last time Veeba raised money from a position of distress. Three years later, in 2018, Veeba reportedly raised $6 million from Verlinvest, a private Belgian family investment company, and existing investors such as DSG and Saama Capital. By FY19, the company managed to take its operating revenue to Rs239 crore, and had a loss of Rs17.4 crore.