Beyond Khao suey: How Burma Burma is stepping on the gas

For nearly 10 years, the bootstrapped, under-the-radar restaurant chain has navigated the unpredictable F&B industry and grown slow and steady. Now it's going on an expansion spree

A lot can happen over coffee, as a popular beverage chain will tell you. But a whole lot can also happen over khao suey, a Burmese noodle soup. Ask Chirag Chhajer and Ankit Gupta.

Chhajer and Gupta were friends from Utpal Shanghvi school in Mumbai, but both went their own ways post-school—Chhajer studied in Australia and then joined his father’s textiles business, while Gupta, who trained in hospitality, worked at the Taj Mahal Hotel for two years before moving into his family’s hospitality business. On work, Gupta would occasionally travel to China, where Chhajer’s family, too, had an office. “Once we happened to visit China together and the two of us got talking," says Gupta. “We were friends, had similar business ethics, and both of us wanted to diversify into a new venture."

Gupta’s mother’s family had lived in Burma [now Myanmar] for over two decades and had migrated to Mumbai only in the late 70s, so Burmese food was quite common at his home. In fact, it would be on the menu whenever relatives and friends visited, and Chhajer was no exception. “At that time," says Chhajer, “the only khao suey I had eaten was at restaurants. And those were nothing like what I had at Ankit’s home." When Gupta suggested the two launch a Burmese restaurant, he didn’t need much convincing.

In 2013, with about Rs 1.1 crore of their personal funds, the two started Hunger Pangs Pvt Ltd, the parent company, under which the first outlet of Burma Burma, a vegetarian, no-alcohol venture, was launched in 2014, in Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda area. The idea was to set up an all-day eatery to introduce Mumbai to food beyond khao suey, the only Burmese dish diners were familiar with and one that was often appended to the South Asian section of a menu. “On the first day itself, the response was so overwhelming that we had to shut down at 3.30 pm for a break. Ever since, we’ve run in two shifts," says Gupta. “By the first weekend, we had reservations for the next two to three weeks."

Nine years on, Burma Burma, possibly India’s only exclusively Burmese F&B chain, has eight outlets across six cities, with three more in the pipeline. The ninth is set to open in Ahmedabad on August 21, while Hyderabad will get its first outpost in October and Bengaluru its third in November, taking the tally to 11.

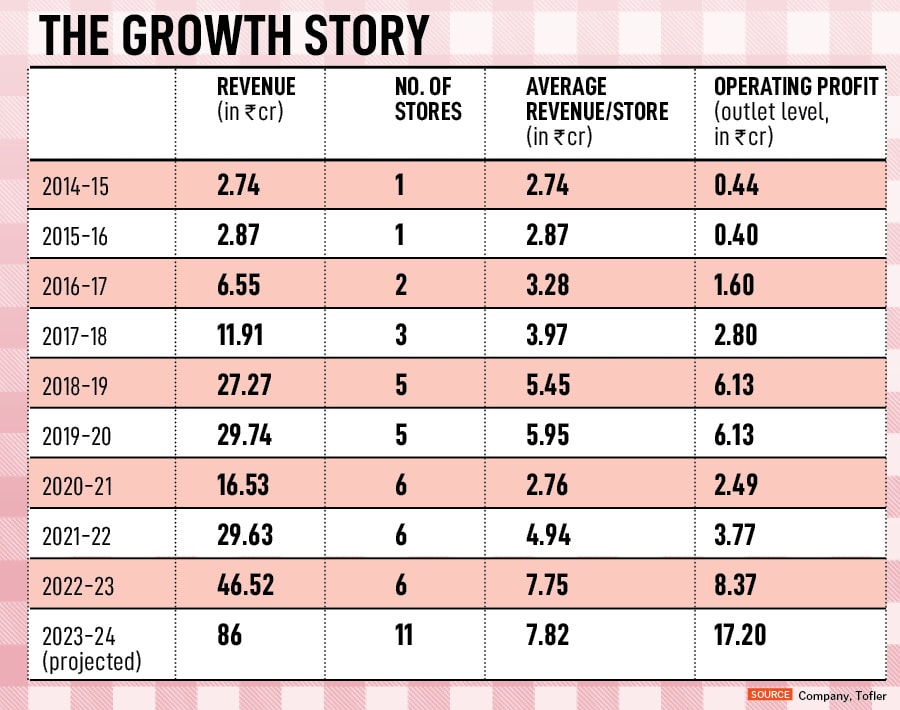

Along with it, its revenue has jumped from Rs2.74 crore in FY15 to Rs46.51 crore in FY23, and is estimated to reach Rs86 crore in FY24. It has also stayed profitable for most of this period, except for the last three years, when, first, Covid hit, and then the company, still bootstrapped, “channelled money towards scaling up and future openings", says Chhajer. But, even through these fiscals, Burma Burma has remained profitable at the outlet level, with Rs8.37 crore in FY23, and a projected Rs17.2 crore in FY24.

Along with it, its revenue has jumped from Rs2.74 crore in FY15 to Rs46.51 crore in FY23, and is estimated to reach Rs86 crore in FY24. It has also stayed profitable for most of this period, except for the last three years, when, first, Covid hit, and then the company, still bootstrapped, “channelled money towards scaling up and future openings", says Chhajer. But, even through these fiscals, Burma Burma has remained profitable at the outlet level, with Rs8.37 crore in FY23, and a projected Rs17.2 crore in FY24.

“That Burma Burma has managed to stay profitable, especially serving a cuisine that the diners were unfamiliar with, makes it an outlier," says Ravi Wazir, founder and CEO of Phoenix Consulting, who has worked with renowned brands like Olive and Izumi. “They have managed to find themselves a blue ocean amidst a clutch of restaurants dying."

Burma Burma’s healthy balance sheet comes despite the lack of alcohol, which typically brings in about 20 to 30 percent of an order value in casual- and fine-dining restaurants. But, says Chhajer, the lack of alcohol on the menu helps them cut down on the turnover time of a table by one to one-and-a-half hours. “If you order drinks with your food, you wouldn’t want to be rushed through your meal," he says. “Without alcohol, a table can be turned around in 90 minutes."

The restaurant’s vegetarian fare, on the face of it, stands in contrast to Myanmar’s strong tradition of non-vegetarian food seasoned with ngapi, a fermented shrimp or fish paste, a condiment integral to its cuisine. But Chhajer and Gupta [both hailing from vegetarian families] feel they aren’t limited by their menu. “While we don’t want to ride a vegetarian wave, it’s equally true that Burmese food isn’t just non-vegetarian. Theravda Buddhism, which is practised in the country, has a three-month retreat akin to a Buddhist Lent, where the Burmese abstain from non-vegetarian food," says Gupta. “That apart, many of their dishes are indigenously vegetarian, with the addition of the shrimp paste." At Burma Burma, the shrimp paste is replaced with the tua nao, an umami flavour bomb made with soybean paste, while mock meats, vegan fish sauce, and proteins such as tohu are used to replicate the taste of a non-vegetarian meal in Myanmar.

“Vegetarianism has contributed to Burma Burma’s success rather than being a drawback," says Anoothi Vishal, culinary analyst, historian and author of Business On A Platter. “The brand is unique and caters to a family audience across age groups, which is crucial for success given that there is no alcohol. My mother, too, likes it, for instance."

Much of Burma Burma’s expansion—six out of its current eight outlets—has come in its bootstrapped avatar. The company raised its first external funding only in November 2022, a pre-Series round of $2.1 million led by Negen Capital. Says one of the investors who didn’t want to be named: “This is a cluttered space, so we wanted to invest in a company that stands out. Burma Burma came across as a clean concept and when we did some on-ground work, we realised it has a deep following: People who like Burma Burma, really love Burma Burma."

With the funds, and another round it’s looking to raise post-Diwali, the company wants to hit the accelerator. “We’ve opened one outlet and three more are coming up in this calendar year, while eight to nine are planned for next year," says Chhajer.

It’s a gear shift from its early years, when Burma Burma opened its second outlet, in Gurugram’s Cyber Hub, only two years after the first. That’s because both Chhajer and Gupta subscribe to the philosophy of organic growth, and want to finetune concepts over months and years before taking it to a wider audience. That includes travelling to Myanmar at least once a year, first to explore the cities and then dig into its regions to bring back the best of rural and tribal cuisines.

It’s a gear shift from its early years, when Burma Burma opened its second outlet, in Gurugram’s Cyber Hub, only two years after the first. That’s because both Chhajer and Gupta subscribe to the philosophy of organic growth, and want to finetune concepts over months and years before taking it to a wider audience. That includes travelling to Myanmar at least once a year, first to explore the cities and then dig into its regions to bring back the best of rural and tribal cuisines.

“Rural Myanmarese cuisine is more fresh, and lighter," says Ansab Khan, Gupta’s friend and executive chef, Burma Burma, explaining how each visit has helped him uncover a unique nuance. “Tomatoes are grown in the state of Shan, so it’s used a lot in their style of cooking. Hilly regions bordering China are known for warm broth, coconut is predominant in the cuisine of the regions bordering Thailand. Every visit gets us excited because we discover dishes beyond the typical four or five that are well-known."

The measured growth is also ascribed to a deep dive into the location of an outlet. “We open an outlet because we fall in love with a location. When we opened in Mumbai, there were only a few eateries in Kala Ghoda. We bet on it because it was a business district on one hand, with the Bombay Stock Exchange and the high court nearby, and would also draw clients from nearby residential areas like Colaba, Walkeshwar, and the local hotels," says Gupta. “Now, it has turned into an eating district filled with restaurants, fashion houses, art galleries. Our revenues have almost doubled at this outlet."

Gupta and Chajjer have followed the same principles with their other outlets, opening up, for instance, at the hugely popular DLF Mall in Noida Sector 18, or on 12th Main in Indiranagar, where most of Bengaluru hangs out. “The knack of extensively researching locations,and identifying markets, rather than just opening up an outlet, requires time," adds Gupta. “We don’t want to compromise on the location even if it means having to pay extra rent, because we need the right footfalls and visibility at our outlets."

While the per seat revenue of Burma Burma outlets doesn’t vary wildly, the two outlets in Bengaluru give the company the maximum yield in terms of absolute revenues, buoyed by the size of the restaurants—at 2,200 sq ft carpet area, and 90 seats, the Indiranagar outlet is nearly double their first in Mumbai (1,100 sq ft) or the 1,200 sq ft in Delhi. “Bengaluru is the best market for us right now given the rentals are just right, as opposed to Mumbai and Delhi that have steep rentals," says Chhajer. “Typically, we break even in 24 to 30 months, but in Bengaluru, we got our money back in 12 months." It has given the duo the gumption to open an even bigger second outlet on Bengaluru’s Brigade Road, with 20 additional seats. “In three months, it has reached nearly 95 percent of the revenue of what Indiranagar has done in the last five to six years."

Chhajer and Gupta are now gunning for bigger and bigger spaces as they embark on the expansion spree—the Kolkata outlet, their fifth, is 2,500 sq ft, while the upcoming one in Hyderabad is expected to be 4,000 sq ft. And despite inflation impacting household budgets, they are confident they will be able to fill the seats. “We are a price-conscious restaurant with about Rs1,200 APC (average per cover). Our price point will bring us footfalls," says Gupta.

“Food-led brands necessarily see slower but more steady and long-lasting success, rather than bars, which rely on constant novelty and buzz to differentiate them in a cluttered market," says Vishal. “Restaurants fold up in less than 10 years when there is no depth in the food, the food is easy to find elsewhere, and the concept relies on alcohol without being distinctive. Burma Burma is a classic example of a well-thought-of cohesive concept."

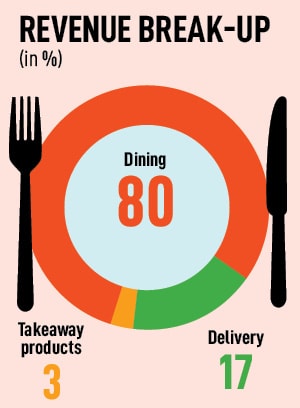

While Covid hit the brakes in Burma Burma’s plans just as it had begun its scaling up journey—bringing down revenues from Rs29.74 crore in FY20 to Rs16.53 crore in FY21—the company amped up its delivery portfolio during this time, launching a cloud kitchen in Mumbai. It brought in a new set of consumers post-Covid, who not only headed to the brick-and-mortar eatery, but also contributed to its rising delivery revenues: While delivery accounted for roughly 3 percent of its revenues pre-Covid, it shot up to 25 percent in the intervening two years, before settling in at a healthy 18 to 20 percent at present.

In order to augment the at-home experience further, Burma Burma also started a line of snacks and condiments in 2022 that has now grown into six types of tea and nine SKUs for food. Five months ago, it launched a range of artisanal ice creams.

While a few plans are afoot for the brand in 2024, Chhajer doesn’t want to divulge much. “That’s for the next story," he laughs. “But all I can say is running a restaurant isn’t easy. That’s one of the reasons we just stuck to one brand. It’s far easier to have four mediocre brands than one fantastic brand."

Just like that bowl of khao suey.

First Published: Aug 09, 2023, 10:48

Subscribe Now