Can trust be the new currency for iD Fresh Food?

Co-founder PC Musthafa is experimenting with a business model based on trusting consumers. Will it pay off for the largest idli/dosa batter company?

L to R- Shamsudeen TK, Jafar TK, Noushad TA, Musthafa PC Abdul Nazer (seated)

L to R- Shamsudeen TK, Jafar TK, Noushad TA, Musthafa PC Abdul Nazer (seated)

Image: Courtesy iD[br]April, Oberoi Park View, Kandivali, Mumbai

The ritual starts around 7.30 am. Every morning, a white Maruti Omni enters Oberoi Park View, a gated residential community in Mumbai’s western suburb of Kandivali. The driver, who is accompanied by a helper, parks the car, leaves the doors wide open and steps out of the society. Residents then make a queue while maintaining social distancing, pick up packed ready-to-make breakfast products such as idli/dosa batter, parota and paneer from the car—as many packs as they want.

The ritual is unusual for many reasons: There is no sales person collecting money no security guard manning the van no vending machine installed to deposit money. And there’s nobody keeping a tab of how many packs each resident is picking up.

The vehicle is one of 42 at multiple locations in Mumbai that follow the same routine every morning. To an outsider, it would seem like a charitable act against the backdrop of the nationwide lockdown since March. Seven months on, the vans are still coming, and the goods vanish within an hour or so even as nobody really keeps a watch.

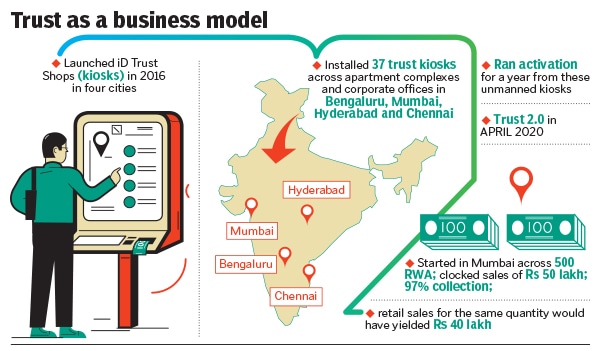

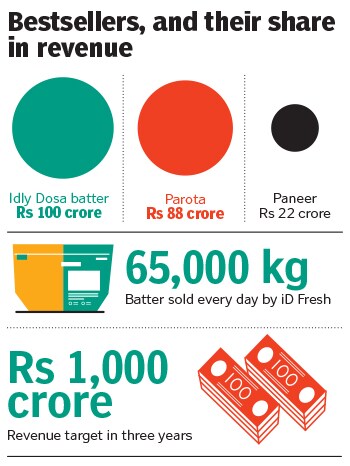

PC Musthafa, though, knows somebody is. “God is watching them,” says the co-founder of iD Fresh Food, a Bengaluru-based ready-to-cook fresh food brand, which sells over 65,000 kilos of idli/dosa batter every day. Musthafa—who calls the vans ‘Trust Shops’—started the pilot across 500 resident welfare associations (RWA) in Mumbai in April. ‘Trust Shop 2.0’ caters to customers in residential areas in Mumbai, during the Covid-19

‘Trust Shop 2.0’ caters to customers in residential areas in Mumbai, during the Covid-19

Image: Courtesy iD[br]If the idea was simple—an innovative way to beat the pandemic blues as retail stores were shuttered—the thought behind it was equally elementary: Trust the consumers. “It has to be 100 percent trust, and 0 percent verification,” smiles the 47-year-old entrepreneur. One RWA member coordinates with iD Fresh and places the order through WhatsApp or call. Once the vans deliver the products, the member informs the residents who collect the products, and pay at their convenience through e-wallets. “Nobody calls them for payment. Nobody knows how much each of them bought. We just trust them,” adds Musthafa. The implicit trust, and with it the business model, seems to be working. Since April, iD Fresh has clocked sales of Rs 50 lakh from such trust shops in Mumbai. Amazingly, only 3 percent of customers did not pay up.

The implicit trust, and with it the business model, seems to be working. Since April, iD Fresh has clocked sales of Rs 50 lakh from such trust shops in Mumbai. Amazingly, only 3 percent of customers did not pay up.

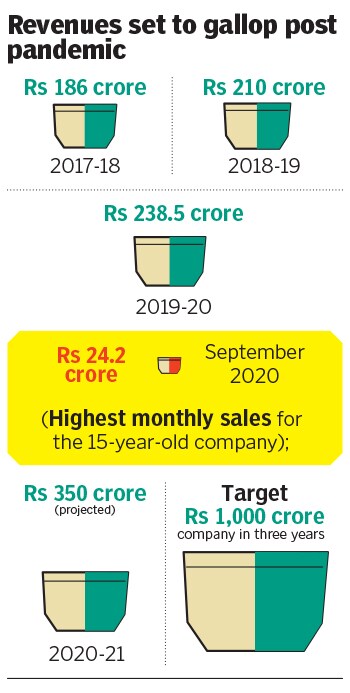

The maths, says Musthafa, works out brilliantly. Had the company sold the same quantity through the traditional retail outlets, collections would have been lower by Rs 10 lakh due to retail commission and wastage. Aided by the pandemic tailwinds, the company clocked its best monthly sales in September at Rs 24.2 crore. The target now is to become a Rs 1,000 crore company in three years, up from Rs 238.5 crore in fiscal 2020. The gritty entrepreneur, who quit a job at Intel in 2008 to join his four cousins full-time to sell idli/dosa batter, is confident of getting there. The secret recipe? Trust.  EARLY THRUST WITH TRUST

EARLY THRUST WITH TRUST

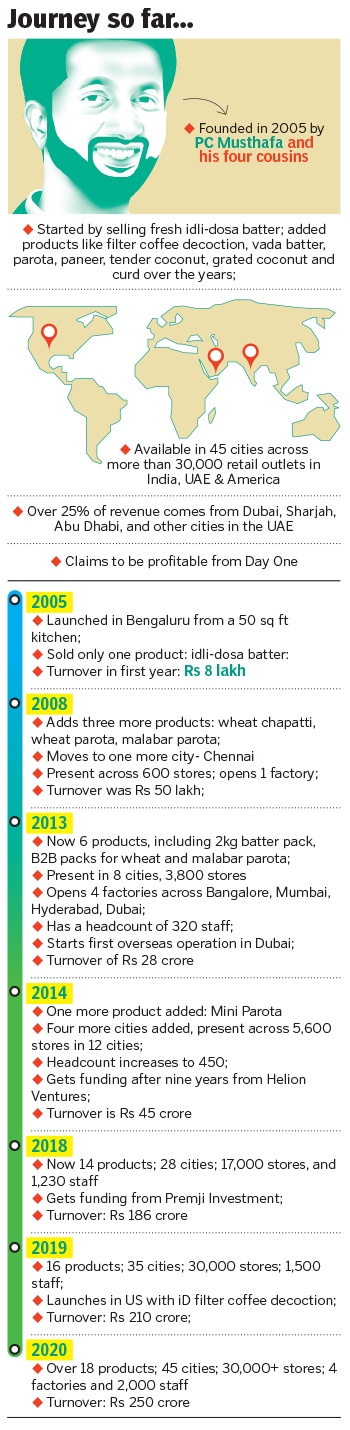

Rewind to 2005. A grinder, mixer, sealing machine, weighing scale, second-hand scooty, a 50 sq ft kitchen, and Rs 50,000…that’s how it all started for Musthafa and his four cousins who had been running a small kirana store at Indiranagar in Bengaluru. Idli/dosa batter supplied by a local maker was one of the many items available in the store. Customer feedback on the batter quality, however, was poor. And in that feedback lay the genesis of iD Fresh Food.

It didn’t begin very well, as consumers didn’t trust the new offering and iD was perceived to be yet another idli batter cottage operator. There was also a perception issue about packaged food. “Anything packaged, especially in wet form, was perceived to be unhygienic,” Musthafa recalls. “It took us nine months to sell 100 packets a day.” What didn’t help is that the founders knew little about the food business. “Forget food technology, we were not experienced in making breakfast (items),” he adds.

The business plodded along till 2008, when Musthafa quit his job and took the plunge full-time. The scale achieved was modest: Selling 2,000 kg of batter every day, and revenue of Rs 50 lakh. In three years, the company grew, but there were mistakes made along the way the most notable was trying to enter into multiple food categories. “We started trying everything. And we failed in everything,” says the cofounder. The good part, though, was that the business was still profitable, with no debt or loans.Then came the big Chennai experiment in 2009. The company was selling around 3,500 kg of batter in Bengaluru, and the aspiration was to go to the Mecca of idli-dosa: Chennai. Musthafa moved swiftly, invested all the savings of the company—Rs20 lakh—opened a plant in Chennai and launched batter at Rs 40 per kilo. The move flopped. Rivals were selling batter at half the rate, some even lower than Rs 20 per kg. “Forget profit, their MRP was not even the cost of my raw material,” he recalls. Musthafa didn’t want to play the price game. The competitors, he explains, were buying rice from the public distribution system at as low as Re 1, and adding loads of soda to make the batter fluffy.

iD struggled to pay employees for over six months, as the focus on Chennai meant losing ground on the home turf of Bengaluru. Musthafa was fast running out of money. Taking loan from banks was ruled out. “We don’t pay interest, we don’t take interest. It’s against our ethical values,” he says. There was another reason to avoid a loan. “EMIs kill creativity in individuals and business,” he says. The only option left was to exit a bleeding Chennai market, which he did after one-and-a half years. “We experimented, but killed the wrong project at the right time. I think that really worked for us,” he says. The focus shifted back to Bengaluru, where more products and innovations were launched.

In fact, innovation is what helped the company establish trust. “There is no rocket science in idli/dosa batter. Anybody can make it,” says Musthafa. “But not all can innovate,” he adds, sharing a string of innovations starting from packaging. A new sealable and reusable batter pack, inspired by a boat, was designed. Then came product innovations. A wet grinder that could churn out 1,500 kg of batter per hour a proprietary machine that mimicked handmade layered parotas paneer made from concentrated lemon juice without any chemicals or acids and vada batter packs that helped users to get the perfect shape—including the hole in the middle.

Today, iD Fresh is present in some 45 cities with 18 products. Its backers are satisfied with the progress. For PremjiInvest, the family office of Wipro founder Azim Premji which reportedly invested Rs 150 crore in 2017-18, iD Fresh is an exciting area of investment not just in terms of returns, but also long-term value. “iD Fresh has consistently and efficiently managed to leverage technologies and capabilities to develop innovative solutions,” said a spokesperson in an emailed response. Despite the Covid impact, iD has been successful in maintaining its business momentum. “PC Musthafa has been instrumental in building a brand that is based on trust,” the spokesperson said. The brand has an extremely loyal set of customers across cities (with minimal marketing expenses) who swear by the product quality, he added.

FLIPPING THE BUSINESS MODEL

India, says Anil Joshi, founder of Unicorn India Ventures, has historically been working on a trust-driven business model. Much before the advent of modern stores and super markets, the country had—and still has—millions of small kirana stores (neighbourhood shops). “The business model was nothing but trust,” says Joshi, explaining how the transactional relationship worked. Consumers would go to the local store, buy their grocery and daily needs and would pay after a month or so (the salaried would do so whenever they got their salaries). “It worked on trust,” he says. Musthafa, he reckons, has flipped the model. “He has empowered the customers by placing complete trust that they won’t default.”

The business model, though, can be a double-edged sword. “The business of trust is not easy,” says Joshi. Musthafa knows a bit about that in 2016, he first experimented with Trust Shops across Bengaluru, Chennai, Hyderabad and Mumbai. Though the pilot was encouraging, the cracks were visible. At some of the retail shops where the experiment was conducted, people deposited fake currency coins--even Monopoly coins—to pick up products. The malpractice continued for a while, but Musthafa persisted. After a few months, the same set of shops started showing better results. “Emotions work. Indians are trustworthy,” he says.

Image: Courtesy iD[br]For marketing experts, the biggest advantage of a trust-based business model is emotional bonding. “It’s a glue. Once you trust consumers, they won’t go anywhere. They stick,” says Ashita Aggrawal, marketing professor at SP Jain Institute of Marketing and Research. Musthafa, she reckons, has understood the deep consumer insight that trust begets trust. So far consumers were asked to trust the brands. Now brands need to trust them. “The chances of striking success by taking such unconventional path are high,” she adds.

Image: Courtesy iD[br]For marketing experts, the biggest advantage of a trust-based business model is emotional bonding. “It’s a glue. Once you trust consumers, they won’t go anywhere. They stick,” says Ashita Aggrawal, marketing professor at SP Jain Institute of Marketing and Research. Musthafa, she reckons, has understood the deep consumer insight that trust begets trust. So far consumers were asked to trust the brands. Now brands need to trust them. “The chances of striking success by taking such unconventional path are high,” she adds.

For Musthafa, though, the path to success started with hardship and failure quite early in his life. A failure in Class 6 proved to be a turning point. Except maths, he flunked in every subject. The failure haunted him. It wasn’t just the loss of a year. “It changes everything. It’s a miserable experience,” he says.

What helped was support from parents and teachers. “I wanted my sweet revenge. I wanted to prove others wrong,” he says. In the first term exams in the following year, he topped in maths but failed in other subjects. He persisted. “Success in maths gave me confidence, and confidence resulted in more success,” he recalls. By the end of year, Musthafa topped in all subjects. There was no looking back since then Musthafa went on to do his engineering from the National Institute of Technology, Kozhikode, and an MBA from IIM-Bangalore.

“The failure in class 6 was the turning point in my life,” he says. Failure, he adds, is the best way to learn, whether at studies or in business. What made the journey more challenging for him was the financial background of his family. “My parents skipped a meal to pay for my expenses. But they trusted me, and I paid it back.”

Can trust be the new currency? Is such a model financially viable? Musthafa doesn’t have even an iota of doubt. ‘Trust me, this model could be the future of the world,” he says. You get much better profitability and you become a much loved brand. “The best way for someone to trust you is to trust them,” he smiles, as the entrepreneur gets ready to go deep into the business of trust.

(Illustrations by Sameer Pawar)

First Published: Oct 28, 2020, 16:26

Subscribe Now