How India's boAt became the fifth largest wearable brand in the world

The inside story of how boAt, a homegrown consumer electronics upstart, took the wind out of the sails of foreign wearables giants

(Image: Edric George for Forbes India)

(Image: Edric George for Forbes India)

December 2016. The Chinese storm had started to batter India. The biggest Indian handset player Micromax—and second in the smartphone pecking order after Samsung—had been brutally cut to size: From 17 percent market share in the January-March period to five percent in the December-ended quarter. Lava, Karbonn and Intex, too, were on skid row. The forecast looked gloomy. Chinese players—led by Xiaomi, Vivo and Oppo—were likely to kick up a tsunami. Meanwhile, in Gurugram, Aman Gupta knew there was something terrible about the timing of his new venture, a consumer lifestyle accessories brand boAt, which he co-founded with Sameer Mehta in November 2016. “Indians were getting out. Chinese were coming in,” he recounts. “People started writing our obituary even before we were born,” he says. The boat was likely to get rocked before it could set sail. Gupta, though, was keen to navigate choppy waters. “I was looking for my kick.”

Kicks did come from all fronts, and were of all kinds. Banks didn’t believe in his story and declined to lend investors shied away from putting money in an Indian hardware venture which was pitted against the Germans, Japanese, American, Chinese and a battery of local players consumers didn’t know what boAt was as there were over 200 brands vying for attention. boAt, recalls Gupta, was entering into a commoditised market.

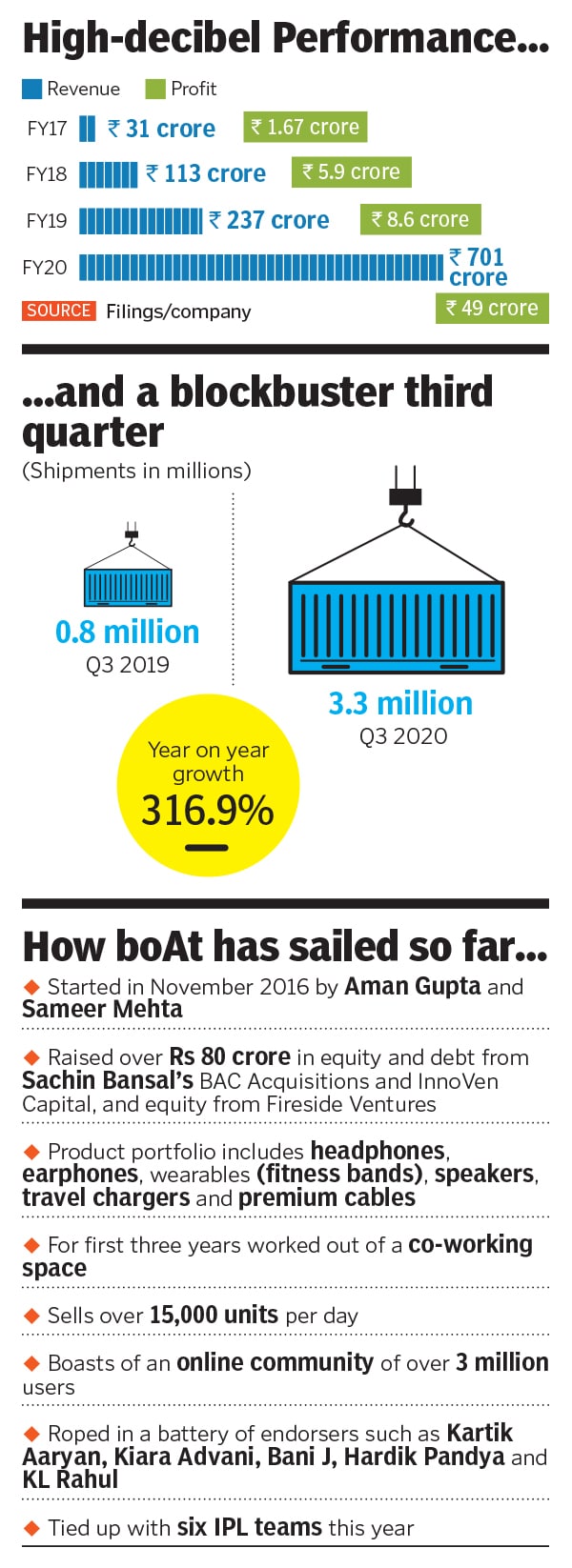

Undeterred, Gupta kept at it. The co-founders pumped in ₹15 lakh each and set sail their bootstrapped journey by selling mobile cables and chargers. In the first year, it weathered the storm to post sales of ₹31 crore, and a tidy profit of ₹1.67 crore. In the next fiscal, it added wireless earwear products and speakers to its portfolio, and grew close to four times. “We had an earn rate, and a zero burn rate,” Gupta claims.

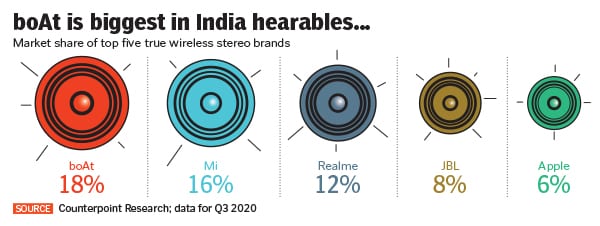

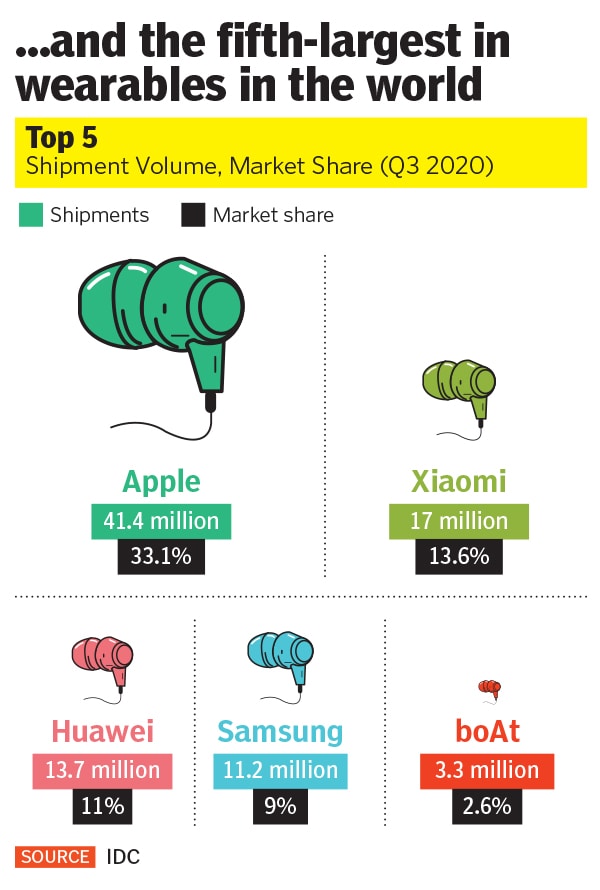

Fast forward to December 2020. boAt has become the fifth biggest wearable brand in the world in the third quarter this year. Back home, it has overtaken Apple, Samsung, and Xiaomi to become the biggest. Revenue stood at ₹701 crore in FY20, and profits at ₹49 crore, the brand sold 15,000 units every day within a three million-plus online user community, it tied up with six Indian Premier League (IPL) teams this year, and roped in as many as 14 brand ambassadors from Bollywood and cricket. “We have disrupted the space, and we will continue doing that,” he says. The high of becoming the fifth biggest in the world, Gupta underlines, lasted just for a day. “Now I am looking for another high, another kick,” he smiles.

boAt, reckon industry analysts, got the wind in its sails at the right time. “It identified the gap in the market quite early,” says Jaipal Singh, associate research manager (client devices) at IDC India. The earwear market, which was just a few thousands units in 2017, started to become big from 2018 onwards. The Indian market size was 1.6 million units in 2018. A year later it exploded to 8.5 million. The uptrend got a massive tailwind in the pandemic year. As work and school shifted to homes, laptops and earwear sold like hot cakes. In the first nine months of 2020, the market pole-vaulted to a staggering 17.3 million. What also helped was a corresponding fall in the price of the products: Average price of true wireless stereos dipped by 48.6 percent year-on-year to $57 in the third quarter this year. Unsurprisingly, the market bloated to 10 million units in this period. boAt’s focus on the entry-level segment, finding a sweet spot in terms of pricing, aggressive marketing and advertising and a tight focus on quality aided its exponential growth, adds Singh.

The uptrend got a massive tailwind in the pandemic year. As work and school shifted to homes, laptops and earwear sold like hot cakes. In the first nine months of 2020, the market pole-vaulted to a staggering 17.3 million. What also helped was a corresponding fall in the price of the products: Average price of true wireless stereos dipped by 48.6 percent year-on-year to $57 in the third quarter this year. Unsurprisingly, the market bloated to 10 million units in this period. boAt’s focus on the entry-level segment, finding a sweet spot in terms of pricing, aggressive marketing and advertising and a tight focus on quality aided its exponential growth, adds Singh. A sharp focus on quality, and a differentiated positioning, is what helped boAt when it started. In fact, boAt did a Havells. What shot the electrical equipment label into instant limelight was its unique value proposition: Wires that don’t catch fire. boAt did something similar with the cables, the first product it rolled out. It identified the pain point of the users: Frequent snapping of the mobile charging cable.

A sharp focus on quality, and a differentiated positioning, is what helped boAt when it started. In fact, boAt did a Havells. What shot the electrical equipment label into instant limelight was its unique value proposition: Wires that don’t catch fire. boAt did something similar with the cables, the first product it rolled out. It identified the pain point of the users: Frequent snapping of the mobile charging cable. The solution offered was unique: Cables that don’t break. ‘Switch to indestructible cable’ was the message, and it resonated well with the consumers. “It got us into consumer minds, and we took off,” Gupta recalls.

The solution offered was unique: Cables that don’t break. ‘Switch to indestructible cable’ was the message, and it resonated well with the consumers. “It got us into consumer minds, and we took off,” Gupta recalls.

Gupta got hooked to the music, and ideology, of legendary reggae singer and writer Bob Marley. ‘Love the life you live, and live the life you love’ became his mantra. The chartered accountant, who took to accounting because his dad wanted him to, started charting an ambitious and independent path. It all culminated with boAt. There was no looking back for the MBA graduate from Kellogg, who had stints with Citi and KPMG.

What also gave Gupta an edge was a slew of India-specific innovations he rolled out. Much of India is humid throughout the year. boAt launched water-resistant and sweat-proof hearable products. Products were tweaked to make them dust-resistant and sturdy. Ample care was taken to enhance mike sensitivity, as Indians love the thump of bass. “We brought bass to Indian handsets,” he says. The brand started talking to the consumers in their language millennials started identifying themselves with the product and for the first three years word-of-mouth spread like wildfire for the direct-to-consumer brand. “We didn’t have any legacy. So we were fearless,” he says. The only thing, he lets on, the brand ensured was to get the four Ps of marketing right: Product, price, place and promotion.

Another P that Gupta and his co-founder now need to fix, and get right, is production. The company gets its products made by contract manufacturers in India, China and other countries. Mehta, for his part, has started to look into the issue. “We launched our first power bank and wall charger this year. Both are made in India,” he says. Most of the mobile accessories, he claims, are now made in India.A pandemic year, tense India-China relations and a changing geopolitical reality have made manufacturing in India all the more imperative. “It’s an opportunity to be excited about. The need to become self-reliant is more important than ever,” he says. boAt, he points out, has embarked on building products in the country.The journey, though, won’t be easy. Reasons: Lack of infrastructure, and absence of scale. Singh of IDC explains the practical issues and ground reality. In the wearable category, most vendors depend on imports. Though there are exceptions—GOQii assembles wristwear and Samsung recently started assembling watches in India—the share of devices assembled in India remains negligible. “Mostly 98 percent of wearables devices are still imported,” he points out. Smartphone and desktop categories have been so far the most successful stories in terms of assembling in India. But, beyond that, other device categories depend on imports.

Cost has been a significant factor for vendors to prefer imports over assembling in India. The smartphone industry is much bigger in value terms and the focus of government through incentives has helped vendors to shift manufacturing to India. However, the wearable industry isn’t as lucky. Not yet. “Certainly, it will take many more years to make this shift,” Singh contends. The challenge for boAt, though, won’t be setting up manufacturing in the country. The fight, reckons Singh, is going to come from Chinese rivals like Xiaomi and Realme.

Gupta, for his part, is fearless.

“Only the paranoid survive,” he says. The bigger the challenge, the higher is the kick. “boAt’s journey as a lifestyle brand has just started,” he adds.

First Published: Dec 11, 2020, 14:11

Subscribe Now